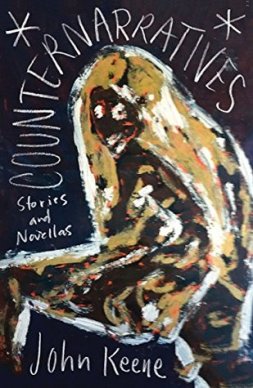

Stretching over a span of four centuries, Counternarratives is a collection of stories and novellas that defies simple description or classification. In just over 300 pages, John Keene manages to challenge and reinvent the way we think about historical fiction by subverting the conventional narratives again and again, peering into dark corners, and prying the lid off of stories not typically part of the grand narrative tradition that has dominated so much of contemporary American literature. First off, for Keene, America has a broader scope. This is the New World, primarily the United States and Brazil—the two countries most closely associated with the slave trade—but over the course of this book we also venture into Mexico, the Caribbean and across the ocean. The characters, primarily, though not exclusively, of Black African heritage, are drawn from history, the arts, and the imagination; and demonstrate a strong will to run against the currents of normative discourse within which they would have otherwise fallen under the radar or been rendered invisible. In allowing their lives to flourish on the page, Keene is effectively queering history. Many of his characters are either implicitly or explicitly queer with respect to sexuality or gender, but all of them through their stories, push up against accepted mythologies, inverting or “queering” them in the process.

The earliest narratives in this collection tend to keep some distance from the subject at hand, some even have an investigative documentary feel, complete with maps inserted into the text. Over the course of the book, the control of the voice shifts, as characters begin to take command of their own stories (mid-way through the powerful central piece, “Gloss, or the Strange History of Our Lady of the Sorrows” Carmel, the mute protagonist, starts to “speak” through the written word, abbreviated and phonetic at first, then increasingly fluid over time) until eventually, as the accounts draw closer to the present day, internalized, experimental stream of conscience narratives begin to come into play. With any collection of shorter works there is always the risk that the stories will begin to blur at the edges, losing distinction from one to another. Not so in this case. Although the themes and characters are not directly connected, this evolving style of storytelling—from the relatively dry historical reportage of the opening pieces, through more traditional narrative accounts to the disembodied, disturbing dialogue of the closing entry “The Lions”—provides a continuity that serves to create a cohesive work of astonishing depth.

The earliest narratives in this collection tend to keep some distance from the subject at hand, some even have an investigative documentary feel, complete with maps inserted into the text. Over the course of the book, the control of the voice shifts, as characters begin to take command of their own stories (mid-way through the powerful central piece, “Gloss, or the Strange History of Our Lady of the Sorrows” Carmel, the mute protagonist, starts to “speak” through the written word, abbreviated and phonetic at first, then increasingly fluid over time) until eventually, as the accounts draw closer to the present day, internalized, experimental stream of conscience narratives begin to come into play. With any collection of shorter works there is always the risk that the stories will begin to blur at the edges, losing distinction from one to another. Not so in this case. Although the themes and characters are not directly connected, this evolving style of storytelling—from the relatively dry historical reportage of the opening pieces, through more traditional narrative accounts to the disembodied, disturbing dialogue of the closing entry “The Lions”—provides a continuity that serves to create a cohesive work of astonishing depth.

Throughout, Keene demonstrates an enviable capacity to create vivid, memorable characters and breathe life into the vital cross currents of history. He does not allow himself to get bogged down in background detail but allows the time, place, and social dynamics to come to the surface through the wide range of individuals and the varied settings and styles that he allows his narratives, or rather counternarratives, to adopt. And although it may seem strange to speak about these short stories and novellas as if they almost have an agency of their own, that is what it feels like to engage with them. Due to extenuating personal circumstances, my reading of this collection actually extended over the course of three months, but whenever I was forced to put it aside for a time I never feared that I would not return, nor did I find it difficult to lose myself, once again, right where I left off.

Throughout this collection, customary beliefs are routinely challenged through the presentation of lives typically discarded or seen through the lens of the dominant power, in a manner that seeks to restore a level of dignity. Black, Native American and queer characters are granted a reprieve from the more conventional historical portrayal. However, that release, or escape if it comes, is often at a cost. Some of the narratives are abruptly truncated, ending partway through a sentence. In most instances a resolution is uncertain regardless of whether it signals promise or pain.

Throughout this collection, customary beliefs are routinely challenged through the presentation of lives typically discarded or seen through the lens of the dominant power, in a manner that seeks to restore a level of dignity. Black, Native American and queer characters are granted a reprieve from the more conventional historical portrayal. However, that release, or escape if it comes, is often at a cost. Some of the narratives are abruptly truncated, ending partway through a sentence. In most instances a resolution is uncertain regardless of whether it signals promise or pain.

By way of offering a taste of this collection, I’ll touch on three pieces. The epistolary novella “A Letter on the Trials of the Counterreformation in New Lisbon” offers a report on the experiences of one Dom Joaquim D’Azevedo, sent in 1629, to attend to matters at an isolated monastery in Brazil where some disturbing occurrences had been reported. He arrives at this remote location, populated by two padres, one brother and their bondspeople, or slaves, to find himself facing what will reveal, in time, a veritable heart of darkness. The atmosphere is charged with an unusual energy from the outset, as the newcomer struggles to get his bearings in his new setting and size up his charges:

Resuming his comments about the monastery, Dom Gaspar could see that D’Azevedo was growing unsteady on his feet, and with a gesture summoned a stool, which a tiny man, dark as the soil they stood on, his florid eyes fluttering, brought out with dispatch. They continued on in this manner, Dom Gaspar speaking—Padre Pero very rarely interjecting a thought, Padre Barbarosa Pires mostly nodding or staring, with a gaze so intense it could polish marbles, at D’Azevedo—detailing a few of the House’s particulars: its schedule, its routines, its finances, its properties and holdings, its relationship with the neighboring town and villages, and with the Indians.

Before long, D’Azevedo settles into a rhythm, feels he is making progress and begins to tutor boys from the town. But strange noises and mysterious sightings inside the monastery begin to unsettle him while outside threats from encroaching Dutch forces escalate, creating an atmosphere in which an evil long brewing is brought to the surface. Dark secrets are revealed, D’Azevedo is forced to confront a truth he has long buried, and the identity of the small African servant who seems to be ever present comes to light. This piece is a strong example of evocative storytelling, reminiscent in mood of The Name of the Rose, but reframed within the context of the Catholic Church’s role in the Americas, the clash with tribal African traditions, warring colonial tensions, and questions of ethnic heritage, gender and sexuality.

By way of contrast, “Rivers” turns the tables on a classic of American literature, giving Jim Watson of Huckleberry Finn fame, an opportunity to flesh out the details of his life after the book ended. Jim, now a free man who has reclaimed his own name, James Rivers, is a tavern owner in Missouri when he chances to meet Huck and Tom on the street. Their conversation, is dominated by Tom’s racist jibes, but Jim remains circumspect. He thinks of what he could have told them but chooses not to (“I thought to say…/Instead I said…”), in this way sharing with the reader a full account of the women in his life, his children, his time in Chicago, and his return to his home state, while little is offered to his former acquaintances. There is no joyous reunion, rather the occasion is marked by arrogance on one side, bitterness and suspicion on the other. But as the Civil War looms, another chance meeting awaits.

Beyond this story, the narratives begin to take on an increasingly playful, experimental form in style and content. An especially affecting piece is Cold. Narrated from an internalized second person perspective, this short story takes us inside the troubled mind of Bob Cole, the composer, playwright and producer who co-created, with Billy Johnson, A Trip to Coontown in 1898, the first musical owned entirely by black showmen. It is now 1911, and the voice in his head taunts him, catalogs his losses, his failures, driving his desperate decision to take his life before the day is out. . .

For the last month or two, or five, has it been a year—why can you not remember?—these newest melodies you cannot flush from your head, like a player piano with an endless roll scrolling to infinity. Songs have always come, one by one or in pairs, dozens, you set them down, to paper, to poetry, like when you set the melody of the spiritual Rosamond was whistling as you walked up Broadway and in your head and later on musical paper clothed it in new robes. Then somewhere along the way after the first terrible blues struck you tried to hum a new tune, conjure one, you thought it was just exhaustion, your mind too tired to refresh itself as it always had, that’s why the old ones wouldn’t go away.

The pieces I have briefly touched on just graze the surface of this book. Its relatively short length can be deceiving. Counternarratives offers a demanding, immersive reading experience. It is, at the same time, compulsively engaging and deeply satisfying. I heard reverent talk of it long before I finally picked up my own copy earlier this year and I can fully understand the respect it has garnered even I find myself at a loss to do it justice. Bold and expansive, this is a haunting, unsettling, important work.

Counternarratives by John Keene is published by New Directions in North America and by Fitzcarraldo in the UK.

Such a great book. I’m glad to see people reading it. The Brazilian material is really unusual to see in American fiction. Keene is also a translator, and I keep meaning to read one of the Hilda Hilst novels he has done.

If you want more in its tradition, Jeffery Renard Allen’s Song of the Shank is a bold, messy novel-length attack on some similar themes. Or you can go back to Ishmael Reed’s novels, like the wild Mumbo Jumbo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found the pieces set in Brazil most interesting. Added some context to the opening of the Olympic Games too. Although I’m American born I’ve lived all my life in Canada so I own less of the American mythology to subvert but one can still sense how “counter” his narratives are.

I just checked the Hilda Hilst novel I own and it is translated by Keene. I’ve looked at it but not read it yet. She is, as I once heard her described, “bat-shit weird.”

LikeLike

“Letters from a Seducer” which I reviewed and you commented that you had scanned just over a year ago. I had to read my own review to remember it (over & above the stunning cover), which tells me it didn’t linger. I have been attracted to “Counternarratives” a few times, based on your review I should bite the bullet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes I remember that you read Seducer. I highly recommend Counternarratives. It is a masterful work.

LikeLike

Roughghosts, there is no easy way to say this. But I know you were very close to her. Please read the comments section of the following link – https://theblahpolar.wordpress.com/2016/08/18/dont-what-shut-up/comment-page-1/#comment-14822

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fuck. Thank you for letting me know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just emailed you an important question. I hope this is the correct email, the shaw.ca one.

LikeLike