On the day Grandma did not die, Mum had an unusual headache. Her eye began to run away to the left. My brother took her to Emergency. He came back without her.

The terminal illness of a loved one has centred many moving novels and memoirs, but there is something about Hair Everywhere, the debut novel of Croatian writer Tea Tulić, that sets it apart. The construction is deceptively simple. Almost too simple at first blush. But what unfolds in a flow of very short chapters—some only a few lines, most less than a page—is a sad, gently surreal, fragmentary novel that follows the narrator’s awkward transition from adolescence to womanhood as her mother slowly dies of cancer. Reading like a series of micro fictions, each chapter tells a complete story or, rather, captures a complete memory and, although there is an overall arc to the narrative that evolves, the progression is not entirely linear. It is, in fact, at times rather scattered, mirroring the conflicted emotions of the narrator, and the uncanny suspension of reality that surrounds her family during this time of prolonged stress.

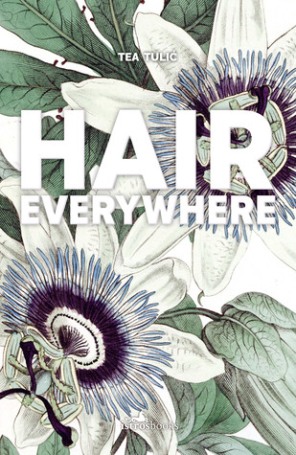

The terminal illness of a loved one has centred many moving novels and memoirs, but there is something about Hair Everywhere, the debut novel of Croatian writer Tea Tulić, that sets it apart. The construction is deceptively simple. Almost too simple at first blush. But what unfolds in a flow of very short chapters—some only a few lines, most less than a page—is a sad, gently surreal, fragmentary novel that follows the narrator’s awkward transition from adolescence to womanhood as her mother slowly dies of cancer. Reading like a series of micro fictions, each chapter tells a complete story or, rather, captures a complete memory and, although there is an overall arc to the narrative that evolves, the progression is not entirely linear. It is, in fact, at times rather scattered, mirroring the conflicted emotions of the narrator, and the uncanny suspension of reality that surrounds her family during this time of prolonged stress.

Mum

(Wants to Come Home Again)When Mum is lying in bed with no make-up on, then she becomes fractious. When she talks to me, I stare at the tip of her tongue. It’s white. I tell her to write everything down on paper. Then she writes how she needs painkillers, which nurses are rude, or what she has eaten that day. When she asks me, writing on the paper, if she will be going home for the weekend, I am both happy and unhappy. But that decision is not mine to make, it is up to the white coats of Olympus who shake the neck of my faith.

They are still saving money on the lighting in the corridors.

The narrative voice is naked, spare, and unflinching. Deaths—accidental, random, and natural—are regularly recounted. Strangers, relatives, and an assortment of pets meet unfortunate ends. The dispassionate accounting feels like an attempt to diffuse the narrator’s anxiety about her mother’s health. There is also a matter-of-fact recording of bodily functions that speaks to the messiness of both adolescence and illness. Having found herself thrust into a caregiving role when she is still in need of support and guidance herself, the narrator seems to be trying to strike a balance between her childhood memories and the mature responsibilities she has been forced to take on. She visits her mother at the hospital daily and supports her when she is occasionally allowed to leave, comforts her through the chemotherapy and resulting hair loss. But back at home she has a younger sister and an ailing grandmother to look after. And although the male characters, her father and brother, tend to appear as peripheral presences, they are not absent. Rather, their silent pain weighs heavily on the household. Her father in particular, is out of work, and crushed with grief and financial fatigue. His daughter is well aware of this.

If this sounds like a dreary and morose read, fear not. There is a melancholy beauty to the prose, allusions echo throughout the course of the fragmented narrative and a measure of controlled sarcasm or mild black humour lightens the tone. This is an essential quality of the narrator’s effort to cope. However, nothing can hide the very real emotional and physical toll of the balancing act she is forced to play between her mother, grandmother, and younger sister. On the cusp of womanhood, she is almost suspended in a grey space where her past and future prospects, hopes and dreams, are bound by the obligations she has to the family members who depend on her. But she does not talk about that directly, what she alludes to is the snake in her stomach. Fear and anxiety are literally eating away at her.

While I watch her lying in bed, I can feel the umbilical cord between us. Something I have tried to cut a thousand times already. And now I hold onto that invisible cord as though I were hanging from a bridge.

Woven into the fabric of the story are continual appeals to the indifferent doctors and nurses, to the church, and to local superstitions, folk healers, and herbal medicines. The family fears that they cannot afford to fight the illness adequately, but the cancer is relentless and, as the narrator reminds her brother at one point, even rich celebrities have lost the battle. As her mother’s prognosis worsens, the grandmother, weakened and ill, but hanging on, grows increasingly bitter as she questions the God who refuses to take her after her husband and other children are all gone and now this last surviving daughter is dying. She seems destined to be “left alone” once more.

In the end, there are no miracle cures, no last minute reprieves. And for those left behind, life goes on, ever haunted by memories. What remains is this unusual and affecting novel of illness, loss and grief.

Tea Tulić was born in 1978 in Rijeka, Croatia. Hair Everywhere was originally published as Kosa posvuda in 2011 and has since been translated and published in Macedonia, Serbia and Italy. The English translation by Coral Petkovich was published by Istros Books in 2017. Further excerpts from the book can be found at B O D Y.

As you know, I recently lost both my parents within 18 months of each other – and I can’t bear to read books like this. (Even a review is difficult). I’ve never found any solace in them, or any other of the oft-recommended books about grief like the CS Lewis one. Music is what helps me…

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s interesting, I don’t think this book is intended to bring solace, per se, but I may have been reading my own experience against it. I lost both of my parents, eleven weeks apart and this was the second Christmas since their death. I was alone on Christmas and missing my mother most painfully; I’ve been having bad dreams and waking up anxious every morning. But I read this book on Christmas Day and saw in it it how much more difficult it is to lose a parent when one is young and thrust into the caregiving role so abruptly and also how the dynamics of the multi-generational central European family came into play. I don’t know if that helped at all, but I found myself both entertained and deeply moved by this odd, unusual novel.

LikeLike

I think I’d find a lot that is familiar in this book about the Central European lifestyle, families and hospitals (and it’s easier to read it before my parents die). You must have done a good job of distancing yourself from your own situation while reading it though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This book has a bit of a morbidly funny side, and the loss of a parent in adolescence has a different intensity, I should think, than the loss when one is older.

LikeLike

I’m not sure I could handle this one either – although it’s two and half years since I lost my dad and nearly one since mother-in-law passed, I find myself getting too close to the subject and feeling that I’m getting nearer that stage myself too. When you lose your parents you feel exposed – at the top of the family tree with no protective branches above you – and I only have my mother and our complicated relationship between me and that.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Considering I was missing my parents so much this year and had no one at all to spend Christmas with, I did not find this book at all difficult. I found it strange comfort and felt less lonely reading it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can see how powerful this must be with the excerpts you have included. I so love translated literature, and it’s ability to cast a fresh perspective on our lives.

LikeLiked by 1 person