“There are no people anywhere who don’t have some mental illness. It all depends on where you set the bar and how hard you look. What is a myth is that we are mostly mentally well most of the time.”

– Mark Vonnegut, MD

A couple of years ago I happened to hear an interview on CBC radio, as part of a series on mental illness. I was, at the time, of the mind that my own issues with mental illness were well managed. A present fact but a distant reality. However, something about this conversation stayed with me.

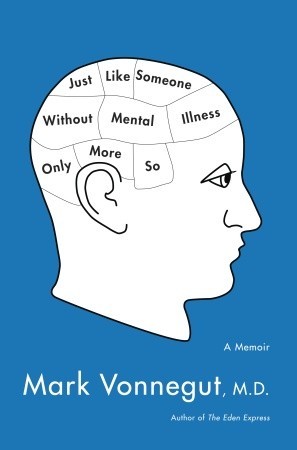

The guest was Mark Vonnegut, son of the late author Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Mark grew up in Cape Cod, in the years before his father’s writing brought fame and fortune. I listened with interest to his very personal account of how, despite diagnosis with a serious mental illness, he applied and was accepted to Harvard Medical School. He went on to become a respected pediatrician. After my breakdown this summer I debated returning to the the fine accounts, like An Unquiet Mind, that had originally guided me to an understanding of my newly acquired label. Then I remembered Mark’s memoir Just Like Someone Without a Mental Illness Only More So and within minutes it was on my Kindle. But I only decided that I really needed to read it this weekend as my symptoms and anxieties continue to persist.

Mark writes in an honest and matter of fact way about the trail madness has left through his family, tracing a legacy of depression, suicide and alcoholism going back generations. His mother heard voices and received message from license plates but once the episode passed she was able to rationalize it. When Mark’s aunt and uncle died within a month of one another leaving four troubled orphans, his parents took them in even though they had neither the money nor the capacity to manage. His oddly prescient mother had been stockpiling supplies for their arrival in advance, as her helpful voices had advised.

Mark writes in an honest and matter of fact way about the trail madness has left through his family, tracing a legacy of depression, suicide and alcoholism going back generations. His mother heard voices and received message from license plates but once the episode passed she was able to rationalize it. When Mark’s aunt and uncle died within a month of one another leaving four troubled orphans, his parents took them in even though they had neither the money nor the capacity to manage. His oddly prescient mother had been stockpiling supplies for their arrival in advance, as her helpful voices had advised.

Mark was a loner spending a lot of time fishing and playing imaginary games in the woods around his home in Cape Cod. The oldest child of the family he grew up poor in the fallout of the the Depression. His father was a ineffectual used car salesman for many years. Mark was 21 before his father became a rich and famous author seemingly overnight.

Caught up in the hippie movement of the 60s, Mark followed many of his peers to Canada to join a commune in BC. He lived off the land, contemplated the meaning of life and experimented with drugs. And that is where he first encountered his own voices. In 1971, at the age of 23 he experienced three major psychotic breaks that landed him behind the locked doors and plexiglass windows of a Vancouver hospital.

“Among the things I grew up thinking about mental illness was that it was caused by other people or society treating you badly.I also knew that once people were broken they didn’t usually get better and the ones least likely to get better were paranoid schizophrenics, which is what I seemed to be.”

Retrieved by his father, Mark returned to the US where, with ongoing treatment, he continued to recover. The voices faded to the background. He published a book about his experiences and articles advocating for an understanding of mental illness as a biochemical condition, in strong opposition to the RD Laing inspired philosophy that was popular at the time (and has recently resurfaced). Somewhere along the way he decided that he wanted to go to medical school himself. Against all odds, and with pathetic math and science marks, he applied to one school after another. Incredibly Harvard gave him a chance.

Over the years that followed, Mark dedicated himself to his studies and his internship. By this point he had recognized that he was bipolar (not a schizophrenic who responds to lithium as he had been told), but even then, the schedule of an intern is grueling. During these years he also married, bought a house and started a family. The model of normal and healthy he figured his mental health issues were history.

Then 14 years after his third psychotic break, several years into a successful pediatric practice, the voices returned to taunt him. The trigger was his realization that he was fueling his high stress schedule with a two pack a day smoking habit along with 5 or 6 beers, half a bottle of wine, a few shots of bourbon and a sleeping medication to round off the day! Hardly a surprise then that his effort to quit cold turkey should trigger a psychotic break.

Although he sensed things were falling apart he resisted seeking help in a hospital. Driven by an absolutely irrational fear planted in his head by his voices he attempted to throw himself through a third story window. The window smashed but he fell back into the room. Unfortunately he ended up in a straightjacket on a gurney in the hallway of the very hospital where he had completed his internship and taught a course.

Although my own manic resurgence following an extensive period of wellness was somewhat less dramatic than Mark Vonnegut’s, it is only a matter of degree. Yet in time he was able to return to work and it has now been more than 25 years since his last manic break. His ability to rebuild his life and career even in the face of abject humiliation is an inspiration. And I am fortunate that I have neither smoking or alcoholism to contend with. But his story stands as stark reminder that with bipolar you must take the medication that keeps you stable and monitor your own level of energy. If we become complacent we risk an unwanted replay, no matter how long we have been well.

This book was published in 2010, so It was not available when I was first coming to terms with my diagnosis. Perhaps if I had read it when I first heard the interview I might have been able to head off my more recent experience. But then again, a manic person is a slow learner because that high just feel so good. Especially in contrast to the draining and despondent opposite end of the cycle.

I would recommend this memoir to anyone interested in mental illness, especially those who understand what it is like to experience psychosis. Its casual, relaxed style makes for an easy read but, as a practicing physician, Vonnegut has some depressing observations about the decline of health care in his own country. Most importantly though, he leaves those of us who live with mental illness with a sense that we can get better, we can stay better and if we fall, we can get up and move forward.

That is exactly what I need to remember right now.