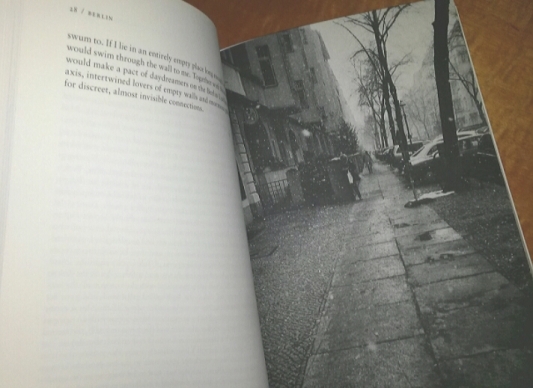

“We only know their story as they told it. Like in books. The only way their story can be told is the way they want to tell it. Isn’t that beautiful? Like a fairy tale. The only pictures we’re left with are the ones our minds created, as we listened to their storytelling.”

The back cover of Slovenian writer Goran Vojnović’s award winning novel, The Fig Tree, promises a “multigenerational family saga…spanning three generations”—exactly the type of description that typically has me thinking twice if not turning away altogether. However, trusting on the strength of Vojnović’s Yugoslavia, My Fatherland—a tightly woven tale of a young man who discovers that his father, long thought dead in the bloody conflicts of the 1990s, is not only alive, but a fugitive war criminal—I had no hesitation to take on this newer (2016) work, recently released from Istros Books in a translation by Olivia Hellewell.

The Fig Tree is an ambitious undertaking. It is multigenerational in the sense that we all exist within the framework of those who came before us and those who will follow. Here the central concern is that of the narrator, Jadran Dizdar, a man in his 30s who is, it seems, adrift within his own life. His grandfather has just died, perhaps under curious circumstances, his father has been gone for many years, his mother is bitter and resentful, and his wife has just walked out on him and their young son. He is trying to make sense of himself by coming to understand the decisions and actions of those around him. But is he avoiding asking the questions only he can answer?

The Fig Tree is an ambitious undertaking. It is multigenerational in the sense that we all exist within the framework of those who came before us and those who will follow. Here the central concern is that of the narrator, Jadran Dizdar, a man in his 30s who is, it seems, adrift within his own life. His grandfather has just died, perhaps under curious circumstances, his father has been gone for many years, his mother is bitter and resentful, and his wife has just walked out on him and their young son. He is trying to make sense of himself by coming to understand the decisions and actions of those around him. But is he avoiding asking the questions only he can answer?

The story begins in 1955, in Buje, Croatia, close to the Slovenian border where a young Aleksandar Đorđević is due to take up a post as forest warden. Arriving from Ljubljana in Slovenia, the newcomer bears a Serbian name and birthplace, but his heritage is complicated and uncertain. He soon takes a fancy to the nearby village of Momjan where, against the concerns of his pregnant wife, Jana, he decides to build a home—the house where they will raise their two daughters, and where one day the garden will be graced by a huge fig tree. It is also where the very next chapter opens. Moving ahead to the present time, Jana is gone, having faded away in a steady loss of memory, and now Aleksandar, Jadran’s Grandad, has also died. That event and its consequences—his daughters’ differing reactions, his grandson’s suspicion that he may have taken his own life, and his cremation and burial—form the backbone upon which will Jadran flesh out the story of his family’s near and distant history.

As a novel focused on family dynamics, it is natural that relationships—especially those between husbands and wives, parents and children—should be the primary focus of The Fig Tree. And so it is. This is a novel about all the complicated facets of love. Jadran is intent on retracing his parents’ early romance, his own love affair with Anya, and the factors that shaped his grandparents’ final years. But his connection to his father, Safet, who has made himself so strangely absent, is possibly the most nebulous element of all, one that haunts both him and his mother. When Safet disappears to Bosnia in 1992, my immediate thought was that he would get caught up in the war. However, his existence in Otoka where he assumes residence in his grandmother’s empty house, is at once mundane and mildly eccentric. He is perhaps trying to connect with his own family’s past, while escaping the family and life of his present. Five years after his departure, his son comes to visit. In his father’s absence, Jadran had created a Bosnian dad fantasy that Safet could not even begin to live up to. He has to come to terms with the truth of the man who is not an idealized hero but:

just like the person who was waiting for me at the bus station in Bihać: scrawny and greying, oddly dressed, the sort of person who offered his hand and asked how my journey was, and whether I was hungry, the sort who, after I replied that I was, glanced around confusedly, not knowing where to take me to get something to eat; unprepared, lost.

Their brief reunion is awkward and strained, both parties are uncomfortable, but the reader may well wonder if there is discomfort in the son finding an unwelcome reflection of himself in the father.

Some of the most powerful passages of The Fig Tree trace the gradual decline of Jadran’s grandmother Jana following a likely stroke. Aleksandar’s complicated reactions as his wife gradually slips away from him—loss, guilt, frustration, redefined love—is wonderfully imagined. It is also one of the spaces in which the wars which tore apart the Balkans enter the narrative:

I know who that is, she said to him, turning away. It was of no interest to her that the country was collapsing, because that was beyond her comprehension. And what she didn’t understand didn’t interest her. The present became increasingly demanding, and one evening she got up, said that she couldn’t watch any more of it, and left the present behind.

Her world no longer extended beyond the walls of their house, and Aleksandar was left alone with the impending times, with a sense of dread, alone with everything that was happening on the outside.

The conflict and its implications are echoed in personal concerns about ethnic identity and nationality. Jadran’s family is rooted in Slovenia, but he and some of the characters have a complicated heritage—something which always matters on some level but holds greater relevance as the former Yugoslavia comes apart and borders take on new importance. The arc of this story may extend beyond the war, before and after, but underlying tensions and repercussions cross into the everyday throughout.

The Fig Tree is a deeply immersive, highly rewarding novel. However, I would suggest that it might take a little time to find one’s footing within the narrative flow. This is, perhaps, because Jadran can be a somewhat difficult narrator to warm to. At times he seems colourless, willing to slip into the background or even slip offstage altogether, allowing accounts drawn from his parents’ and grandparents’ lives to be told from afar. At other times, when he is front and centre, he can get bogged down in his own mix of blame, bitterness, and limited self-awareness, on occasion even falling into unbroken passages of running thoughts, a near stream of consciousness. Early on, shifts in the storyline seem a little odd, characters and situations are often introduced in a sideways fashion, with explanations and clarifications arriving only in time. Yet, once one gets accustomed to the manner of telling, the characters and their stories become increasingly compelling. And if there is a strong current of uncertainty running through Jadran’s account, it is not surprising, there is so much he is trying to resolve, so much that may never be known:

The coffin is no longer visible. The cranking of the mechanism that lowered it down has stopped. The sound of the furnace, however, grows louder. I hear the last of Grandad’s secrets burning, I hear it all disappear. All that remains is doubt, for doubt is the only thing that’s eternal.

Then, as the novel nears a close, Jadran makes a confession that I did not see coming, but one that reveals what I had already sensed. It’s a twist that brilliantly reframes everything—not only the text that has just been read, but the notion of writing a family history at all.

The Fig Tree by Goran Vojnović is translated from the Slovene by Olivia Hellewell and published by Istros Books.