Each August is Women in Translation Month, a time set aside to promote women writers from around the world who write in languages other than English and, of course, encourage increased translation of these authors into other languages so that they may be more widely read. This initiative, started by blogger Meytal Radzinski, is now in its sixth year.

My best ever effort to participate was during 2015, my first year as a blogger. Not only was this before writing critical reviews and editing commitments started to creep into my reading time, but I was also recovering from a cardiac arrest and could stretch out on the sofa and read without guilt. Doing much else was painful! Since then, each year I have made public or private commitments to toss a few extra appropriate titles on the TBR pile and, if lucky, read one or two. I console myself by remembering that reading women in translation is something that naturally seems to occur throughout the year in the course of my normal reading. As so it should.

My best ever effort to participate was during 2015, my first year as a blogger. Not only was this before writing critical reviews and editing commitments started to creep into my reading time, but I was also recovering from a cardiac arrest and could stretch out on the sofa and read without guilt. Doing much else was painful! Since then, each year I have made public or private commitments to toss a few extra appropriate titles on the TBR pile and, if lucky, read one or two. I console myself by remembering that reading women in translation is something that naturally seems to occur throughout the year in the course of my normal reading. As so it should.

This year I have a few books earmarked for the month (fingers crossed), but I thought I would take a little time to suggest some titles that might not be so well known. They’re all taken from my own bookcases and most are (as of yet) unread.

I’ll start with those that I have in fact read and reviewed. First up, poetry:

From the bottom up:

From the bottom up:

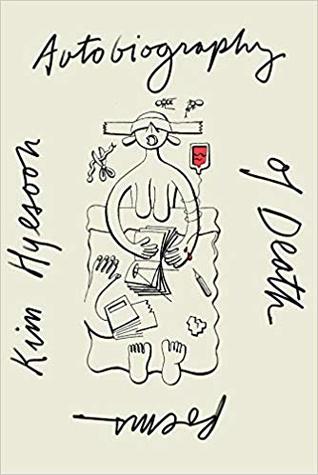

Korean poet Kim Hyesoon won the 2019 International Griffin Poetry Prize for this book Autobiography of Death, a cycle of 49 poems and one longer piece inspired by national tragedies and personal experience. Her daughter’s distinctive illustrations accompany this powerful collection translated by Don Mee Choi.

Thick of It by German poet Ulrike Almut Sandig, translated by Karen Leeder, is a wonderful blend of the magical and the everyday. Fresh and alive.

Finally, Italian poet Franca Mancinelli’s The Little Book of Passage, translated by John Taylor, is a spare and delicate collection that invites rereading. Earlier this year she and I were able to meet and spend a few days together in Calcutta when my visit happened to overlap with a residency she was doing in the city—evidence that reading the world makes the world smaller in unimaginable ways!

*

Second, I wanted to highlight a book I recently reviewed that I am afraid has not had the attention it deserves:

Croatian writer Olja Savičevič’s Singer in the Night features a wildly eccentric narrator and a highly inventive style to tell a story that paints a serious portrait of the world that her generation inherited after the break up of the former Yugoslavia. Translated by Celia Hawkesworth, this book is already available in the UK and well worth watching for when it comes out on October 1 in North America.

Croatian writer Olja Savičevič’s Singer in the Night features a wildly eccentric narrator and a highly inventive style to tell a story that paints a serious portrait of the world that her generation inherited after the break up of the former Yugoslavia. Translated by Celia Hawkesworth, this book is already available in the UK and well worth watching for when it comes out on October 1 in North America.

*

Third, I have an impressive stack of Seagull Books by female authors that I am ashamed to say I have not read yet (save for the poetry title tucked in here). The interesting thing for me about this selection is that although I did purchase many of these books, other titles arrived as unexpected—but very welcome—review copies by writers previously unknown to me.

Most of the above are German language writers; two, Michele Lesbre and Suzanne Dracius are French, the latter from Martinique. The review copy at the bottom of the stack is East German writer Brigitte Reimann’s diary I Have No Regrets.

Most of the above are German language writers; two, Michele Lesbre and Suzanne Dracius are French, the latter from Martinique. The review copy at the bottom of the stack is East German writer Brigitte Reimann’s diary I Have No Regrets.

*

Finally, I wanted to include a couple of translated titles by Indian women writers. Two vastly different offerings.

Translated by Kalpana Bardhan and published by feminist press Zubaan, Mahuldiha Days is a novel by Anita Agnihotri, one of West Bengal’s best known writers. She draws on the decades she spent in the Indian Administrative Service in this story of a young civil servant caught between her obligations to the tribal community she is working with and the state. By sharp contrast, I Lalla, gives a fresh voice the poems of fourteenth century Kashmiri mystic poet, Lal Děd. A detailed introduction by translator Ranjit Hoskote provides a fascinating background to her life and the tradition to which she belonged, opening a world little known to most Western readers.

Translated by Kalpana Bardhan and published by feminist press Zubaan, Mahuldiha Days is a novel by Anita Agnihotri, one of West Bengal’s best known writers. She draws on the decades she spent in the Indian Administrative Service in this story of a young civil servant caught between her obligations to the tribal community she is working with and the state. By sharp contrast, I Lalla, gives a fresh voice the poems of fourteenth century Kashmiri mystic poet, Lal Děd. A detailed introduction by translator Ranjit Hoskote provides a fascinating background to her life and the tradition to which she belonged, opening a world little known to most Western readers.

*

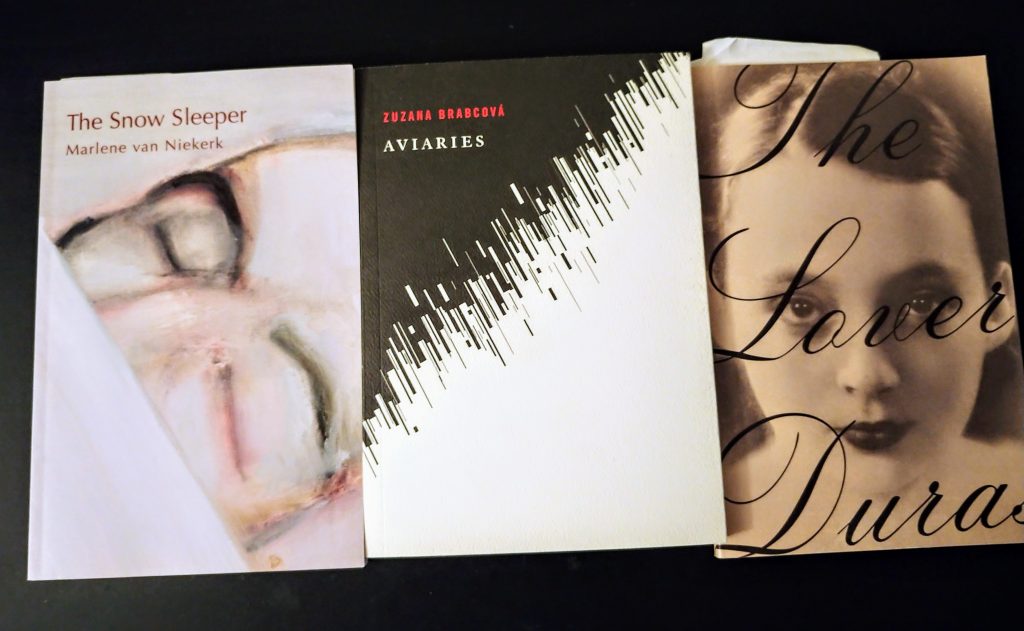

So, what are my best laid plans for this month? I would like to read one or two titles from my Seagull stack—not sure which—and I have a new Istros title Wild Woman by Marina Sur Puhlovski on my iPad in PDF format, but the following three books have been patiently waiting for August:

The Snow Sleeper by Marlene van Niekerk, translated from the Afrikaans by Marius Swart, is a recently released collection of short pieces, including “The Swan Whisperer” which was published as part of the Cahier Series. I ordered it as soon as I heard of it—new van Niekerk is a rare and special treat. Aviaries by Czech writer Zuzana Brabcova caught my attention when fellow readers and reviewers started talking about it so it’s another title I sought out when it was released here this spring. And last but not least, Marguerite Duras’ The Lover is a book I’ve been meaning to read for years now. Will I fit it in this August? Time will tell. And, of course, I reserve the right to change my plans altogether…

The Snow Sleeper by Marlene van Niekerk, translated from the Afrikaans by Marius Swart, is a recently released collection of short pieces, including “The Swan Whisperer” which was published as part of the Cahier Series. I ordered it as soon as I heard of it—new van Niekerk is a rare and special treat. Aviaries by Czech writer Zuzana Brabcova caught my attention when fellow readers and reviewers started talking about it so it’s another title I sought out when it was released here this spring. And last but not least, Marguerite Duras’ The Lover is a book I’ve been meaning to read for years now. Will I fit it in this August? Time will tell. And, of course, I reserve the right to change my plans altogether…

The nice thing about books is that, at least with the old fashioned solid form variety, they don’t vanish at month’s end if you don’t get to them. They will still be there on the shelf waiting no matter how much time I do or do not have to read amid all my other projects on my plate this August!