What do you want me to do? says the First Voice.

I want you to talk a little more, says the Second Voice.

Wasn’t it enough? says the First Voice.

Not yet, says the Second Voice.

What should I tell you? says the First Voice.

Anything. Everything, says the Second Voice.

So hard, says the First Voice.

I know, says the Second Voice. But it’s worth trying.

You mean to work our memory? says the First Voice.

Yes, says the Second Voice. Our scabbed memory.

I don’t remoment anything, says the First Voice. I can’t remoment anything important. Things I remoment are all broken.

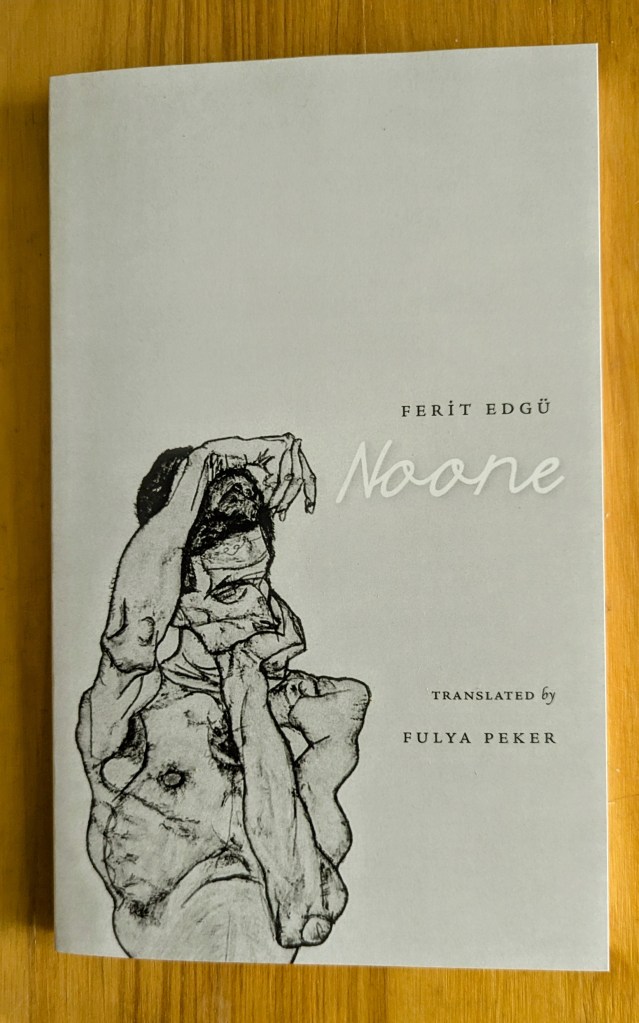

Noone, by Turkish writer Ferit Edgü, opens with a chorus of voices, each with an ascribed character or quality—the Initial Voice, the Alwaysasking, the Broken, the Ramshackled, and so on—setting the stage for the unconventional narrative that will follow. Part I finds us alone with two apparently distinct voices, the First and the Second. It is the depth of winter and the voices converse, debate and remoment—a most striking way of saying remember—as they sit together in a dark and cold dwelling somewhere in a remote mountainous region. Outside wolves and dogs howl. Snow falls without respite. And nearby there are others, village residents who, do not share the same language or culture. The Voices interact to pass the time, waiting for the long winter to end and the roads to open. But are they two disembodied voices, two distinct individuals, or one man trying to find company within himself?

This spare novella, which was composed over the span of ten years, from 1964 to 1974, is a response to what Edgü has referred to as the most transformative experience of his writing life—the nine months he spent, at the age of twenty-four, teaching in the village of Pirkanis in an isolated part of the province of Hakkâri in southeast Turkey. This region, his time there, and its more recent bloody history has influenced much of his writing, including the 2007 novella and 1995 short story collection published together, in Aron Aji’s English translation, as The Wounded Age and Eastern Tales by NYRB Classics. This volume was a runner-up for the 2024 ERBD Literature Prize which will hopefully bring attention to this earlier book. Work on what would become Noone was actually begun while Edgü was in Hakkâri, but the fact that it took him a decade to complete it implies that a certain amount of time and distance was required to articulate and make sense of what had been a profoundly disorienting experience, and, as he says at the outset: “transform a monologue into a dialogue.”

This spare novella, which was composed over the span of ten years, from 1964 to 1974, is a response to what Edgü has referred to as the most transformative experience of his writing life—the nine months he spent, at the age of twenty-four, teaching in the village of Pirkanis in an isolated part of the province of Hakkâri in southeast Turkey. This region, his time there, and its more recent bloody history has influenced much of his writing, including the 2007 novella and 1995 short story collection published together, in Aron Aji’s English translation, as The Wounded Age and Eastern Tales by NYRB Classics. This volume was a runner-up for the 2024 ERBD Literature Prize which will hopefully bring attention to this earlier book. Work on what would become Noone was actually begun while Edgü was in Hakkâri, but the fact that it took him a decade to complete it implies that a certain amount of time and distance was required to articulate and make sense of what had been a profoundly disorienting experience, and, as he says at the outset: “transform a monologue into a dialogue.”

The abstracted doubled character that emerges and recedes during the first part of Noone—the “we”/ “I” / “you” of the First and Second Voices—often resembles a world weary soul, an exile who has travelled far and wide and now finds himself on this mountain top, uncertain how he got there. The Voices share stories, dreams, and memories, often provoking, confusing, or irritating one another. For, as translator Fulya Peker says in her lyrical introductory Note: “Noone compels us to consider the politically imposed idea of ‘the other’ and how this ‘other’ is not somewhere outside, external to us, but within.” To this end, the use of the grammatically incorrect spelling for “no one” is telling. The translator does not explain this decision or its relation to the original Turkish title Kisme, but because the word appears to function as both a pronoun and a noun, it is an affecting choice. Along with “remoment” and an ongoing shifting tapestry of pronoun usage—you, we, I, he—Edgü is repurposing language, perspective, and narrative in a manner that reflects the shifting personal, psychological, social, and political territory within which his story unfolds.

The second part of the novella, while still featuring the two Voices, steps outside of the snowbound dwelling, at least initially, to offer an account of the protagonist’s arrival in Pirkanis, a village comprised of only thirteen houses and one hundred people, so isolated it is ultimately accessible only by horse or on foot. It is an impoverished community with strange traditions, an unfamiliar tongue, and at least one potentially suspicious resident. Life is hard, death is always near at hand, and loneliness takes on a whole new meaning for the outsider who has come to provide medical support. As loneliness begins to take its toll, the isolation is stark and haunting:

He takes a book Opens He quits without reading

He takes an envelope Opens He tears up the letter and throws it away before getting to the end

He opens the lid of the stove & throws the letter on top of the fading ashes

Again he returns to his mattress

Again his eyes are fixed to a spot on the wall

No

His lips are black and blue

Black and blue lips (only) tremble

His teeth are chattering

Dogs are again howling outside

A stranger is approaching

Or the wolves are coming down againWith no period no comma no question with no ending dead night goes on like this in fragments

An interlude like this, in which the dialogue of Voices is temporarily silenced, feels heavy, intense. Our exiled hero is naked. Stark, spare, and poetic, Noone offers an existential, dramatic portrayal of extreme isolation, not only that of the central character, but of the people he finds himself among.

Noone by Ferit Edgü is translated from the Turkish by Fulya Peker and published by Contra Mundum Press.

“The translator does not explain this decision or its relation to the original Turkish title Kisme, but because the word appears to function as both a pronoun and a noun, it is an affecting choice.”

This is so interesting. I appreciate the other examples you’ve pulled, in terms of language usage, too, but this one particularly resonates with me, the idea of a space/an absence being closed up, pulling no and one together.

These prizelists do help with visibility, as do reviews like yours. Of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sadly, Ferit Edgü’s death was just announced yesterday, just as English language readers were beginning to learn of his work. I do hope more translations are on the way—his style is so spare, yet so intense and affecting.

LikeLike

That’s sad, although the publishing industry does seem to respond to these events by bringing other work into print, which is some consolation for readers.

LikeLiked by 1 person