Of late, concern for the environment has fallen out of fashion in much of the world. Where I live, and in any other regions, oil companies, and forestry and mining interests exercise an outsize influence on governments, especially in a world of global economic uncertainty, fueling resistance to monitoring greenhouse gas emissions, investing in clean energy projects or promoting electric vehicles. It’s suddenly become too expensive, too inefficient to worry about the future. Besides, many insist that climate change is a hoax. So by the time we really feel the heat, so to speak, it will be too late to act. What stories will we, or rather our ancestors, tell to make sense of the damage done? Will it even matter?

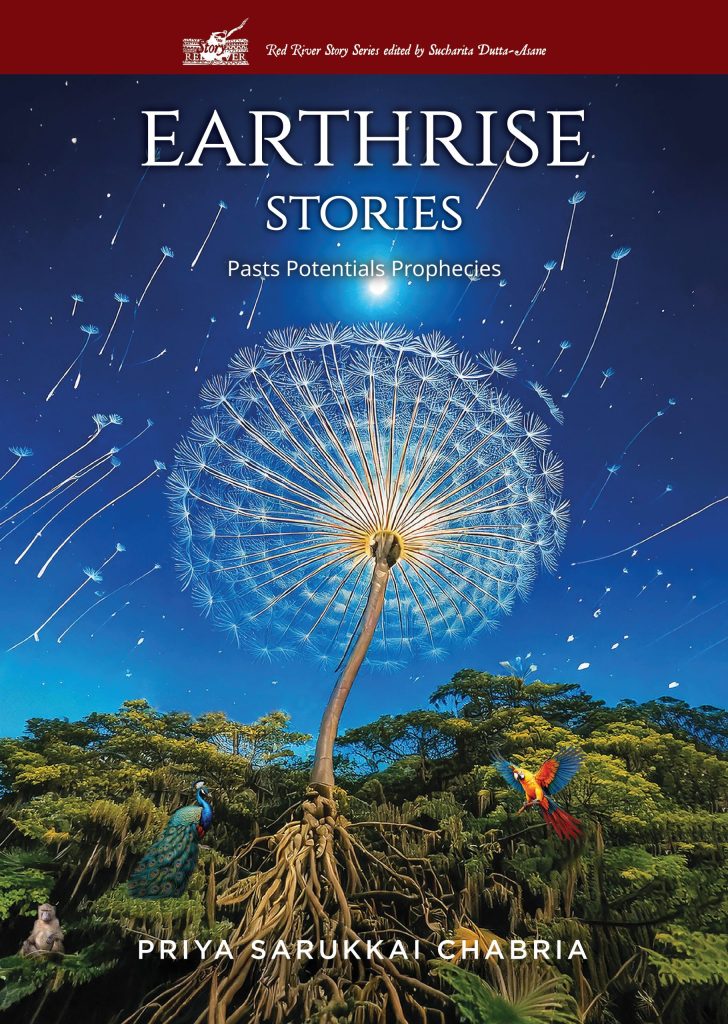

For Indian poet and writer Priya Sarukkai Chabria, the fate of our planet is an ongoing and vital theme. She sees it as a question that arises in the myths and traditions of a distant past, swirls around the influence of technology and artificial intelligence shaping our present existence, and reaches far into the future where an unknown realm of possibilities can only be imagined. Yet, she is prepared to explore new ways of thinking about and envisioning what we have come from and where we may be going. Now a wide-ranging selection of her poignant and thought-provoking fictional imaginings have been gathered in her new book, Earthrise Stories: Pasts Potentials Prophesies.

As a novelist and short story writer, Chabria has long sought expression through speculative fiction, typically with a strong Indian sensibility, and this collection highlights her strength in this genre, along with her distinct ability to flesh out the sensual intensity of her female protagonists, be they drawn from epic literature, or existing on a far distant timeline. But more than anything, these stories form a coherent project in which the reality of climate degradation and what it means for the fate of the planet is a driving force. As she says in her Introduction:

As a novelist and short story writer, Chabria has long sought expression through speculative fiction, typically with a strong Indian sensibility, and this collection highlights her strength in this genre, along with her distinct ability to flesh out the sensual intensity of her female protagonists, be they drawn from epic literature, or existing on a far distant timeline. But more than anything, these stories form a coherent project in which the reality of climate degradation and what it means for the fate of the planet is a driving force. As she says in her Introduction:

I write stories of Earth, and some of the ways we could love her as she spins through our present dark time; the small gem of her seemingly weightless sphere spiraling through space, circling the sun like a prayer, sapphire and emerald as the eye of a dream, summoning tenderness.

Earthrise is divided into six sections, each one featuring a striking illustration by artist Gargi Sharma, and expanding in different spatial directions. “Past Re-Presented” is rooted in mythic times; “Now” searches for grounding in our ever-evolving present; “Ten Years from Now” turns to nonhuman life, natural and artificial; “In the Near Future” reaches deeper into the consequences for nature and a memory of humankind; “In the Far Future” contemplates the possible regeneration of a nearly dead planet; and, finally, “Prophesies that Come True” reintroduces a recognizably human narrator in in one story and offers a comet-focused cautionary tale in the other. Together, the eighteen stories that comprise this volume take the reader on a journey through time and space, marked by a wide variety of shifting voices, styles, and tones.

The opening section re-animates tales drawn from Indian myth, legend, and literary tradition. Characters like the celestial nymphs (aspara) Menaka and Urvaśī are realized as full-bodied sensual creatures rising above their passionate and tragic circumstances to set commonly accepted records straight. Episodes from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana are re-imagined with multi-dimensional, even cosmic, elements to at once reinforce their timelessness and set a foundation for many of the stories to follow.

The mood changes abruptly, however, as we enter the realm of the present day. The stories in “Now” are playful and inventive in style, but darkness and warnings lurk in their narrative themes. War, migration, economic turmoil, ecological devastation, and the increasing presence of robotic and artificial intelligence all feature here. There is even a lecture—or the draft of one—about the promises of a technologically driven future in one of my favourite pieces, “Cockaigne A Reappraisal (Draft) by Dr Indumati Jones (To be presented at UTIIMDS),” a text complete with the professor’s own personal notes to self:

With augmented AI inputs that analyse large amounts of financial data this sector is being steered towards making more predictive decisions in the stock market, and can tailor options to meet the investment patterns of specific financial firms. (Add examples. Quote sources?) On a lighter note, (smile here) Photoshop will be relegated to the past as in-camera devices will automatically correct flaws. Power outages like the one I’m currently experiencing will be out-dated — pun intended! — (smile here) as various AI driven units will be linked to a central intelligence system – as is already occurring in certain Smart Cities worldwide.

Dr Jones’s cynical optimism aside, the atmosphere that dominates the four stories in this section is ominous.

Ten years on, things are no better, flora and fauna are in serious decline (the author setting a fictional report in her hometown of Pune, even) and hopes that damages might be undone are outsourced to the services of a LoveBot who can customize a dream, but has no power to make it come true. Moving on, further into the future, the Eco-Lit exam that makes up the content of one of the stories of the next section, leaves no question about ecological outcomes, but the prose in other tales becomes more poetic, dream-driven and, in one story, “The Princess: A Parable,” folkloric. But the hard reality of the potential fate (or fates) of the Earth and the life she once sustained cannot be denied.

Yet, this is where Chabria’s stories of Earth take a detour from the classic dystopian formula. Although she leaves no question about the destructive tendencies of man and the fragility of life on our planet, when we reach the far distant future, there is the hint of a utopian possibility, however unlikely (and unlike anything we have ever known) that might be. In the two penultimate stories, she envisions variations on a world where life at its most fundamental cellular level has been preserved, integrated with novel notions of consciousness, historical awareness, and the means to reproduce or self-evolve. In this sort of speculative realm, the poetic, passionate energy that fills Chabria’s female protagonists charges her post-human narrators. “Paused,” for instance, imagines a planet where proto or potential lifeforms that can decide how they wish to evolve. But it is a lonely existence, and evolving is a process fraught with challenges. After an aborted attempt, her narrator retreats in a panic:

I trigger TEMP TORPOR in myself. It causes shuddering standstill of all activities. Cessation shocks my systems. Quieten down, please, down. Alarm still volcanoes. Shuush, shuuhh. Quieten to hill size. Rolling boulders. Be still, shuush. Become pebble size. Still, be still. Be spore. Be a drop of silence, a bead of spreading stillness. My systems slow, calm. I’m sliding into deep sleep; almost a hibernating pod again. Scan the damage. I must create low energy compounds to coat the membrane till it can sustain survival. I’m barely born but must manage so much!

Clearly, earthly recovery will be a slow and painful, but re-birth, in this scenario, could be intentional, not accidental. What then?

Earthrise presents many questions, and offers no clear solutions (except, of course, the ones we’re already boldly ignoring). Yet, in drawing on such a vast array of inspirations, from mythology, history, science—natural, physical, ecological— and, of course, poetry, Chabria has crafted a collection that values life, all life, not just the hair-covered, supposedly “Wise Ones.” It is sad and hopeful—a warning, a promise, and a prayer.

Earthrise Stories: Pasts Potentials Prophesies by Priya Sarukkai Chabria is published by Red River Story. (Available worldwide through Amazon.)