Raging winds howl to the vakai trees as their pods tremble in fear.

A land cloaked with countless peaks

yet not an ounce of soul.

It was this cold grim path that he,

the ruler of my heart, chose

over lying in my tender embrace.“What the Heroine Said” – Avvaiyat (translation by Gobiga Nada)

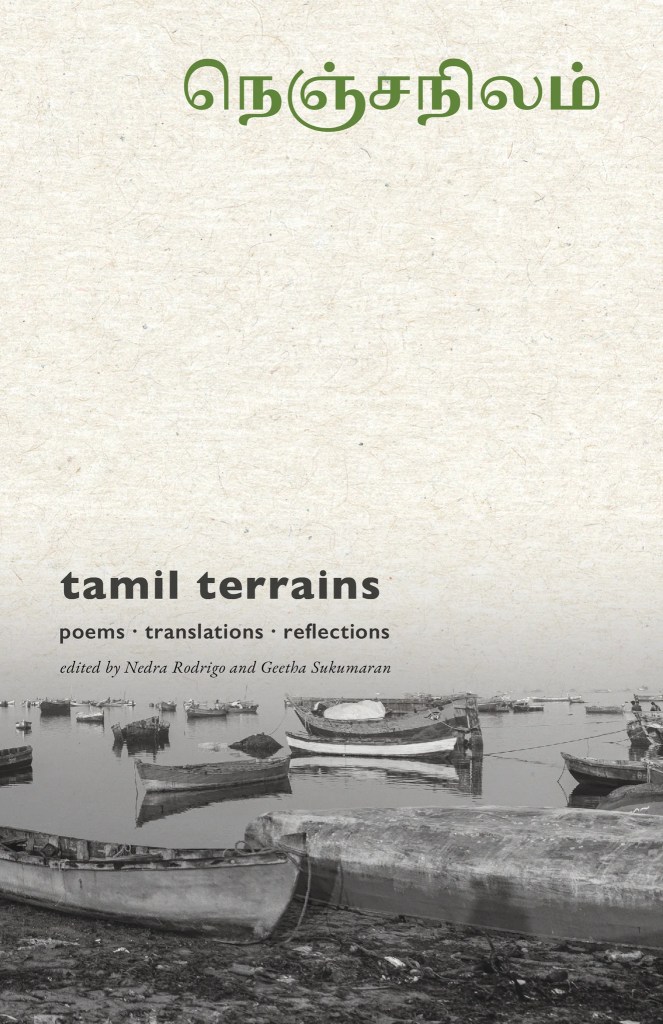

The second in trace press’ translating [x] series, Tamil Terrains, arises from a series of online workshops conducted over six weeks in Autumn of 2022 and Spring of 2023. Editors Nedra Rodrigo and Geetha Sukumaran invited poets and translators from India, Malaysia, Singapore, Ilankai (Sri Lanka), and Canada to explore classical and modern Tamil poetry and enter into conversation about “what it means to translate in anti-racist, feminist, and decolonial ways.” With a history that extends back over two thousand years, Tamil is a language that is deeply entwined with its indigenous landscapes—mountain, forest, field, desert, and coast. But this relationship to land has long been troubled by conflict, colonization, and displacement, so this project also seeks to ask how a connection to these terrains, with its layers and accumulated losses, can be understood in traditional Tamil speaking communities in South and Southeast Asia and throughout the diaspora.

As both Nedra and Geetha, and a number of the participants in the workshops, live in Takaronto (so-called Toronto, Canada), the workshop discussions opened with the question of how diasporic translators “who occupy Indigenous lands as refugee and immigrant settlers, might critically engage with, and contest, ongoing erasures carried out on the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island.” This raises a perspective often ignored, or at best simply addressed with rote land acknowledgements, but one that has deeper, and in our present day, significant implications. In recognition, then, of the ways in which translation has been employed to dismiss the cultures and peoples of Turtle Island, this book opens with Tamil translations of work from two Indigenous poets—Mi’kmaw poet shalan joudry and Michi Saagiig and Nishnaabeg poet Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. The volume closes with an essay by Thamilini Jothilingam, whose family was forced to flee civil war in Jaffna when she was a small child. She reflects on the two places where she feels most at home—her current home in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia and the Vanni region of northern Sri Lanka. Both places carry a legacy of colonial violence.

As both Nedra and Geetha, and a number of the participants in the workshops, live in Takaronto (so-called Toronto, Canada), the workshop discussions opened with the question of how diasporic translators “who occupy Indigenous lands as refugee and immigrant settlers, might critically engage with, and contest, ongoing erasures carried out on the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island.” This raises a perspective often ignored, or at best simply addressed with rote land acknowledgements, but one that has deeper, and in our present day, significant implications. In recognition, then, of the ways in which translation has been employed to dismiss the cultures and peoples of Turtle Island, this book opens with Tamil translations of work from two Indigenous poets—Mi’kmaw poet shalan joudry and Michi Saagiig and Nishnaabeg poet Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. The volume closes with an essay by Thamilini Jothilingam, whose family was forced to flee civil war in Jaffna when she was a small child. She reflects on the two places where she feels most at home—her current home in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia and the Vanni region of northern Sri Lanka. Both places carry a legacy of colonial violence.

Another distinctive feature of this project and the collection that emerged from it, is the desire of the facilitators to gather people who identify as Tamil, regardless of individual fluency, thus opening a point of connection and collaboration to those who may have grown up away from their ancestral homelands. As a result, the approach to translation explored in the workshops and reflected in Tamil Terrains is varied and creative. Participants are encouraged to engage in retelling, re-creation, expansion and commentary, especially with ancient and classical poetry and traditional folk songs. Nedra Rodrigo describes the decision to differentiate types of translation for the workshops—Root, Branch, and Driftwood:

Root as a direct translation from the source text; Branch as a translation supported by a bridge translation; and Driftwood as a transcreation that was inspired by the source text or that archived some aspect of the text.

The invaluable nature of this approach is clearly reflected in the work selected for publication.

The original texts are presented Tamil script, with a few exceptions where the original poem was written in English or where the decision made to use transliteration. At times, several translations of a single poem may follow, perhaps by translators from different geographical areas, or employing different approaches. Sometimes a translation or transcreation may also be accompanied by a reflection that allows the translator to express the thoughts, experiences, and emotions guiding their personal approach to the piece. Such insights are particularly interesting and add another layer to the process of translating or re-imagining a poem or song.

Finally, translation is also recognized as an act of resistance, speaking to the dislocation from homelands due colonial actions, war, and migration, and the displacements of the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island. The poetry selected for the workshops from more recent and contemporary Tamil poets, much of it touched with a measure of darkness and grief, was chosen to encourage exploration of these concerns, understanding that “(r)esistance here does not mean shutting out but opening up to each other, to allow each other the chance to dwell in our imaginations.”

I remember

the Saamiyadi resting after his trance

swatches of vermillion scattered

all over the entrance.

Withered betel leaf, with shrunken veins.

Everyone standing in the dark smoke

yearning for something

enchanted by the words of the Saamiyadi.I remember

we were no further than an arm’s reach.

Even so

between us the distance widened

like these ones on one street

and those ones on another.From “Tree with Broken Shade” by S. Bose (translation by Yalini Jothilimgam)

This volume, reflective of the collaborative spirit of the workshops that led to it, offers an opportunity to appreciate the many complex ways Tamil speaking people, and their descendants who may be spread far and wide, can maintain a connection to the landscapes, traditions, and histories of their respective homelands through poetry and other cultural elements such as art and film. Reaching from the Sangam era (300BCE – 300CE) to the present day, the translations, transcreations, and reflections gathered here combine to make reading this book a very dynamic and moving experience.

Tamil Terrains is edited by Nedra Rodrigo and Geetha Sukumaran and published by trace press.