She put on her bathrobe and sat down at the dressing table, making as little noise as possible. In the mirror her face seemed to her tired and used, like an old glove. Her mouth was set in brackets by two faint, sketchy lines that stopped a little before the slope of her chin, as if the unknown artist had been called away in the middle of his work. Her eyes had that same open, sincere expression as in children who are telling a lie. Three delicate wrinkles lay like a pearl necklace around her neck, and they would dig deeper day by day. Would this face last out her time, this face that bore traces of so many things the world must know nothing about? Did it turn toward her with hostility whenever she wasn’t looking? And what would be underneath, when it fell apart one fine day?

Lise Mundus has an acute awareness of faces, her own and those of others—what they hold, what they hide, what they give away. And it seems to becoming more of an obsession. Not only has the sudden fame that accompanied her publication of a popular adult novel after years of writing children’s books pushed her face out into public view, but of late she has begun to question the motives of those around her. She already knows her husband is wildly unfaithful, she fears that she is losing touch with her children, and she resents the presence in her household of Gitte, the young housekeeper who looks after everything. And everyone. Haunted by crippling writer’s block, increasingly feeling isolated and alone, she begins to overhear hushed conversations rising through the plumbing and from behind closed doors. Her husband Gert has just suffered the loss of his mistress to suicide, and now, Lise is certain, he and Gitte are conspiring to push her to that same end.

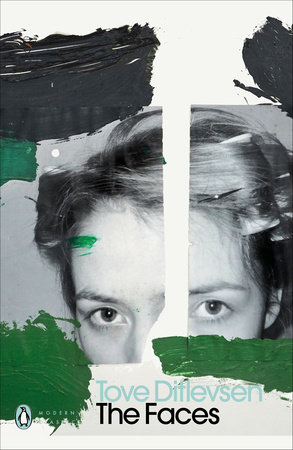

The Faces, first published in 1968 by celebrated Danish writer Tove Ditlevsen, is a sharp, tight portrait of a woman’s spiralling descent into an episode of paranoid psychosis , her hospitalization, and subsequent recovery. Ditlevsen’s personal life was marked by domestic upheaval, addiction, and multiple psychiatric admissions, and she is clearly drawing on lived experience here, but she is doing so with poetic clarity and remarkable insight to impart a sense of what it is like to be unable to distinguish reality from hallucination and yet feel like one has full control of one’s sense, no matter how strange the experiences. However, this is neither memoir nor autofiction. Rather, it is, even through its protagonist’s darkest moments of anxiety and confusion, a story told with great warmth, compassion, and even humour.

The Faces, first published in 1968 by celebrated Danish writer Tove Ditlevsen, is a sharp, tight portrait of a woman’s spiralling descent into an episode of paranoid psychosis , her hospitalization, and subsequent recovery. Ditlevsen’s personal life was marked by domestic upheaval, addiction, and multiple psychiatric admissions, and she is clearly drawing on lived experience here, but she is doing so with poetic clarity and remarkable insight to impart a sense of what it is like to be unable to distinguish reality from hallucination and yet feel like one has full control of one’s sense, no matter how strange the experiences. However, this is neither memoir nor autofiction. Rather, it is, even through its protagonist’s darkest moments of anxiety and confusion, a story told with great warmth, compassion, and even humour.

At first, there is nothing funny about the fragile state Lise is in as we first meet her. She is haunted by memories, appearances, and even the very rooms she occupies. No matter how she tries to hide her concerns, she believes that others are out to exploit her weaknesses—even her best friend Nadia, a psychologist who drops by to visit and strongly suggests that she stay away from the sleeping pills Gitte provides and call her psychiatrist instead. Lise wants to trust her friend, but what she detects in the faces around her and hears whispered behind her back is getting the better of her. She ends up doing the opposite. Convinced that Gert really does want her out of the way, she downs the entire bottle of pills (and immediately calls her psychiatrist to tell him she doesn’t want to die). She wakes up days later, in the toxic trauma centre.

Once she is medically stabilized, Lise is taken to the psychiatric hospital. By this time she is in a state of full-blown psychosis. Voices speak to her from speakers embedded in her pillow and from behind grates in the room to which she has been confined, strapped to the bed, after she failed to settle on the open ward. This room, which is actually a bathroom, becomes her safe space. She can hide here, protected by the voices that alternately attack her and warn her against the nurses and psychiatrist who are all part of their scheme to destroy her. It’s easy for her to believe the danger, she can read in their false faces. Convinced she is being poisoned, she refuses to eat and resists medication.

As the anti-psychotics begin to take effect, Lise starts to accept and embrace her insanity, no longer terrified, but now increasingly alert and wise to the subterfuge that surrounds her. At least, that’s what she thinks. Convinced, for instance, that a nurse has painted her face to look like someone from her past, Lise reasons that she “did it to confuse her and break down her resistance, but [she] saw right through such childish tricks with her healthy, clear sense of judgement.” And certain illusions are especially resistant, no matter how often (and patiently) she is corrected. She continually sees the male nurse named Petersen as her husband, even when the solidity of own perception starts to slip:

‘That’s right,’ said Gert, satisfied. ‘You’re starting to behave quite sensibly.’ His face was suddenly blurred, the way it looks when you’ve forgotten to wind the film and you’ve taken two pictures on top of each other.

‘You have two faces,’ she said, astonished. ‘That’s not allowed. You can only wear one face at a time.’

If the voices and hallucinations that have fueled her paranoia prompted a most desperate, potentially life-threatening action, their gradual retreat into the hard, tactile environment of the hospital ward leaves her fearing that she will be abandoned. Understanding that the manifestations of psychosis is rooted in one’s own disordered thoughts is unsettling, and for a time Lise actively resists the idea that she is moving toward returning home.

As a reader who has experienced an episode of manic psychosis and hospitalization (albeit under very different circumstances), I am always impressed when an author can capture the salient aspects of mental illness—the internal reorientation of reality, the distortion of time— so clearly without sacrificing the literary and poetic qualities that contribute to a good story. Drawing on lived experience is not, in itself sufficient, Ditlevsen achieves this balance through point of view and by keeping her narrative short and focused.

When The Faces opens, Lise is already beset by suspicions and hallucinations, so we come to know her, and those around her, entirely through her increasing warped perceptions. With a tight third person perspective—ideal for conveying madness—there is no ground zero. At first, it’s difficult to tell whether there is a justification for her fears; it does look like there may be some gaslighting going on. Even when she swallows the handful of pills it’s not clear if she has been pushed to the limit by outside forces. Yet, once she’s committed to the psychiatric hospital where she wages her daily struggle against the voices that taunt her and her belief that she is the victim of a grand conspiracy, the extent of her illness becomes apparent. We can “hear” the outside voices of the nurses, doctors and other patients, in concert with what she thinks she hears. Now we have to listen and hope that she will slowly emerge from her psychotic state. The actual state of affairs at home, the “real” nature of her reality so to speak, won’t be revealed until she is finally ready to be released.

The Faces by Tove Ditlevsen is translated from the Danish by Tiina Nunnally and published by Penguin Books. (Also published by Picador)