We take the everyday for granted. The history of the everyday, as Gandhi said, is never written. We don’t write the history of harmony. We write of history with a capital H. The history of strife. The history of the everyday is the history of a time that exists in the blurry lines between memory and forgetting. The days we remember are the days of events, personal, social or political.

It seems such a long time ago that the world slipped into lockdown as a strange, invisible threat began to spread causing illness and death. Where I am in Canada, our first lockdown was the strictest even if it was considerably less severe than in many places. Dramatic charts were hauled out, ominous predictions were made and the outside world suddenly seemed to become a dangerous place. Yet, the feared explosion of cases never materialized except in nursing homes and long term care. We slipped out of confinement into a summer of somewhat reduced freedoms but plenty of elbow room. The consensus: the lockdown was extreme and unnecessary. Of course, it’s impossible to convince a skeptic of the success of a measure by the absence of the thing you set out to prevent.

So we became our own control group. Winter brought a second wave and only when cases and deaths started to rise exponentially were some restrictions brought back. Protestors took to the streets to decry their loss of freedom in the name of an imaginary illness that, even if it existed, was primarily taking only the oldest and weakest among us. Nothing but the flu.

Now as Spring slowly settles in, we are into a third wave, fuelled by variants, striking a much younger cohort and rapidly expanding. The government is responding with weak-kneed measures—even less intense than the last round—figuring we will vaccinate our way out while ICU beds fill up with the sickest group of Covid patients yet. Yes, perhaps fewer of them will die. But anyone who arrives with a serious condition that would normally warrant an ICU bed will have to be weighed for worth, for likelihood of survival, against some young, otherwise healthy Covid patient presently gasping for breath. And people will die who would not have died otherwise. How serious are things? Today the case rate in my city was more than twice that of India.

India. A country that has come to mean a lot to me these past few years is presently on fire—metaphorically and factually. It is painful to watch, heartbreaking to think of. Here in the West, even when things are bad and resources are stretched beyond reason, illness and death is sanitized, hidden behind closed doors, underestimated, forgotten.

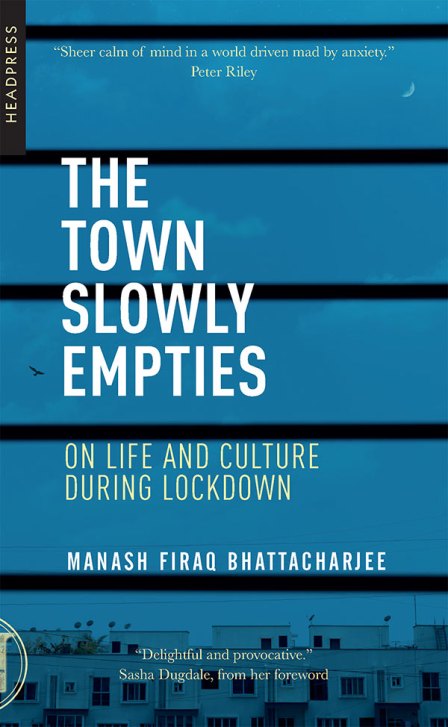

All of this is but a long, yet timely, introduction to my review of The Town Slowly Empties: On Life and Culture During Lockdown by Indian poet and writer Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee. This has proved a very difficult book to write about. In fact, as the present crisis in India began to escalate, I found it increasingly difficult to read. Not that it isn’t good. It is a most wonderful, personal engagement with the early weeks of the sudden, strict lockdown imposed on India last March. Exactly a year ago as I was reading. At first there was a definite sense of déjà vu, but soon the altered routines, unexpected observations, and thoughtful reflections began to feel, quaint, otherworldly, against the horrific backdrop of the second wave now battering the country. Yet, the current state of affairs should in no way undermine the merit of this chronicle of adjustment to the limitations and possibilities of mandated isolation. In truth, it makes it all the more relevant.

All of this is but a long, yet timely, introduction to my review of The Town Slowly Empties: On Life and Culture During Lockdown by Indian poet and writer Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee. This has proved a very difficult book to write about. In fact, as the present crisis in India began to escalate, I found it increasingly difficult to read. Not that it isn’t good. It is a most wonderful, personal engagement with the early weeks of the sudden, strict lockdown imposed on India last March. Exactly a year ago as I was reading. At first there was a definite sense of déjà vu, but soon the altered routines, unexpected observations, and thoughtful reflections began to feel, quaint, otherworldly, against the horrific backdrop of the second wave now battering the country. Yet, the current state of affairs should in no way undermine the merit of this chronicle of adjustment to the limitations and possibilities of mandated isolation. In truth, it makes it all the more relevant.

The Town Slowly Empties—the title comes from Albert Camus’ The Plague—unfolds as a series of journal entries beginning on Monday, March 23, just after a complete lockdown has been declared in Delhi. Within days the entire nation will follow suit with only four hours’ notice. The daily reflections continue until April 14, the end of the first phase of restrictions. Each day’s record is a melange of domestic activity, pandemic progress reporting, political and social contextualizing, philosophical musing, and the sifting of memories, all woven together with literary references, film commentary and a passion for food. Lockdown life offers an uncanny blend of the exceptional and the ordinary. Something frightening is lurking close at hand, just outside the door where the streets have grown quiet, while inside time has expanded, leaving even more empty space to fill, more anxious thoughts to fill it, especially supercharged in those early days.

We have become watchmen, standing guard at ourselves, at our shadows. We terrorize ourselves with caution. We become extremely careful about what we touch, and if we touch, we immediately wash our hands with soap for at least twenty seconds. We are mindful of the merest hint of a sore throat, or rising temperature. We also have the time now to watch others, and not just the human species. We carry the virus in our heads, in our sleep, and some with intense paranoia, perhaps even in their dreams. Fear is our only mode of retaliation. We are brave, we fear bravely. We cannot laugh at ourselves. The absurdity of survival must be taken seriously.

For Bhattacharjee these extra hours afforded by lockdown are measured out in poetry, prose and film. A host of writers and filmmakers become his companions, offering illustrations, examples and inspiration as the days roll by. Along the way he calls upon TS Eliot, Rimbaud, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Fernando Pessoa, Kafka, Agha Shahid Ali, Zbigniew Herbert, Abbas Kiarostami, Satyajit Ray and many others, engaging with their ideas and imagery. This is, then, far more than a record of news reports, readings and recipes, though there is a clear sense of the quotidian routine—waking late, securing provisions, morning tea, making lunch. Each day brings new circumstances, spectacles, and tragedies to process: face masks, Zoom meetings, lost lives translated into statistics, hungry migrant workers desperate to get home. The daily act of processing such experiences through writing opens avenues for the past to enter the stream of the present. Thus, this journal also becomes a memoir and a meditation on memory.

As the days pass into record and reflection, Bhattacharjee will recall moments of his childhood in Assam, his college years, his courtship with his partner, and his pathway to a love of cooking. But the memories he visits are as often collective as they are personal, of mutually shared experiences, or times captured in historical and literary record. For we live not only in our own pasts, but through the lives of others. Under the shadow of Covid-19, we look for meaning not only in pandemics and plagues, but also in disaster. One of the most interesting entries—and now eerily prescient given how the second wave is currently devastating India—moves through film and literature, from Chernobyl to Bhopal, tracing a landscape of disaster in the words of two writers formed in their wake—Svetlana Alexievich and poet Jayanta Mahapatra. Both chronicle the pain and destruction of scientific catastrophe as written on the body and the spirit. Both speak to the necessity of remembering. But how?

Science has no memory. Memory has no science. Science is an idea of progress without memory. Memory is a shelter. Memory looks for shelter. When a scientific experiment goes wrong, it affects nature. The sky, the sunlight, and even the silence turn toxic.

Covid-19 presents a complex interaction between nature, science and society. It is an event that has been anticipated for years, but the degree of disaster experienced reflects lack of planning and uneven response. Vaccines are welcome, if they can be produced and obtained, but the refusal of politicians and people to listen to the scientific advice they do not like—to wear masks, maintain distance, lockdown when needed—has led to unnecessary illness and loss of life around the world. What documentarian or poet will be the one to bring science and memory together to bear witness to this pandemic? For now, we can only meet the moment.

Today many people are starting to imagine a day when the pandemic finally recedes in the rear view mirror. Others are still fighting. Until the world is vaccinated, Covid will still be with us. It may always be with us. With this in mind, Bhattacharajee’s book is both uncomfortable and comfortably nostalgic. There was a sense of global unity to those early days. Yet there is much more within these pages. Reading The Town Slowly Empties is akin to spending time in the company of an intelligent, poetic friend—the sort of person who always has an interesting story to tell, a poem to quote, a book or movie to recommend. To that end, this friend has been sure to leave you, his reader, with a select bibliography, a filmography and extensive notes. You are not left empty handed.

The early months of the pandemic generated a flood of “Lockdown Diaries.” 3:AM, the magazine I was editing for last year, ran such a series as did many other venues. A friend of mine in Bangalore dutifully maintained a daily record, with an eye to economics and social policy among other topics. He has picked up the thread again; at last count it was Day #415. Plague-themed literature also experienced a revival. For a while it seemed as if it was all too much. This warm and thoughtful work reminds me that there cannot be enough. Lest we forget. This experience will look different in a few years’ time, but already our world and our way of being in it has been altered in ways we could not have imagined when we first retreated into our homes in what sometimes feels like another lifetime.

The Town Slowly Empties: On Life and Culture During Lockdown by Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee, featuring a foreword by Sasha Dugdale, is published by Headpress.

I can’t help but admire someone with the self-discipline to keep a record of these days. I am not one who has slipped into inertia, I had productive ways to use my time and I had achievements to show for it at the end of our lockdown. But I could not keep a journal… I wanted to escape into other worlds with books instead.

But in years to come these records will have great value, I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

He mentions that the writing of the journal is a helpful process. And he is reading a lot and watching films along the way!

LikeLike

I go through phases of keeping a journal, but Covid, day after day, no, I just didn’t want to. I started another writing project that I’d been meaning to work on for a long time…

LikeLike

I find it hard to comprehend what’s happened to the world, even after over a year of lockdowns and a completely changed planet. The book sounds remarkable, but I don’t think I could read it just yet. Although as Lisa says, this kind of record will be vital in whatever future we have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do think you would enjoy this, Karen. It is rich in literary content and the writing is wonderful. But against the present context in India everything is thrown into sharper relief.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been struggling to make sense of these numbers, too, the idea that the rates are higher in western Canada than in India but also the fact that the reality of the experience in India is a whole ‘nother. (And not meaning to generalize as obviously from afar Canada to others isn’t imagined in different provinces and I know that India is a whole of many parts too.) I can see where this would be a challenging read at this particular juncture but obviously much to admire in the work. Does it feel like a lot of time has passed since you were editing those pieces for 3AM?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I realize that the case count in India has far greater implications than it ever would in Alberta, but numbers have consequences all the same. Here we have a significant number of Covid deniers (including 17-18 members of the government’s caucus) and to them the death count will always be small (and old people) without thought to what it means to have ICU and acute beds filling up. I despair of the extent to which this has made people more selfish and self-centred. So yes, it feels like ages have passed since editing those essays for 3:AM, but the inward focus that seemed temporary at the time has become intrenched and the real test is if we can remember that this is a global pandemic.

LikeLike