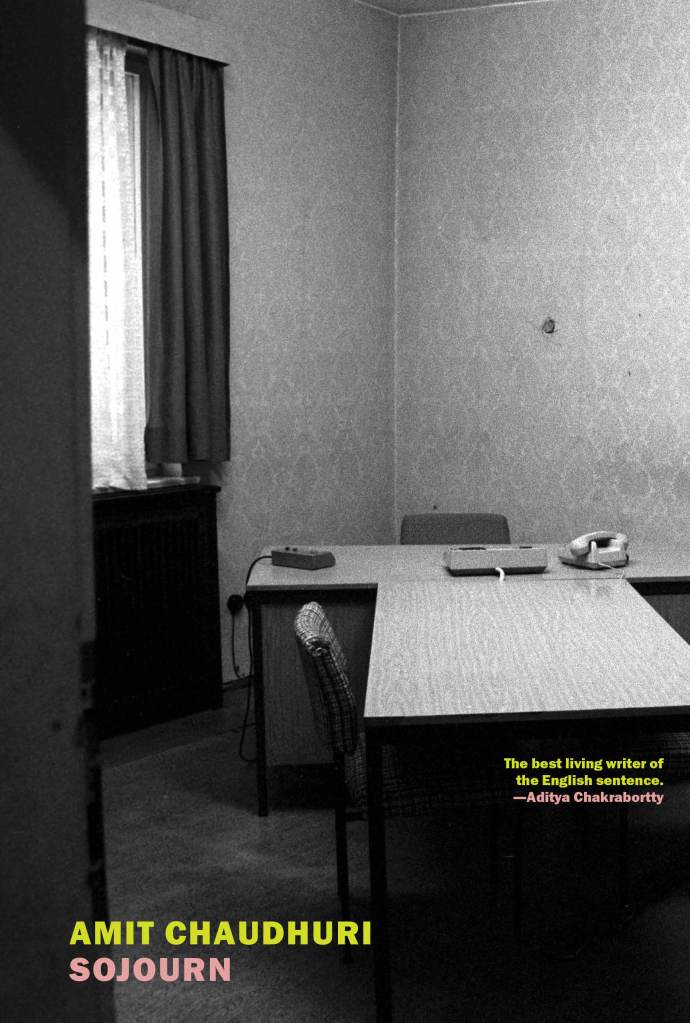

From the opening passages of Amit Chaudhuri’s quiet, lugubrious novella Sojourn, one can already sense that his unnamed narrator, an Indian writer on a four month visiting professorship in Berlin, is slightly out of sync with the world around him, but it’s not clear if it’s simply the strangeness of his environment or some unease he carries with him. It’s not even his first visit to the city, but little seems familiar. He constantly requires directions and gets lost easily. There is, however, a subtle tension running through this lowkey narrative that gradually builds into something more disorienting in this portrait of a man’s shifting relationship to time and place as he enters mid-life.

The year is 2004, fifteen years after the fall of the Wall, but its shadow persists; former demarcation lines and vast areas not yet cleansed of their link to a dark past remain. Residents are inclined to point them out to visitors as if sharing the city’s history with a certain wistfulness, while the narrator tends to react to these spaces as if they hold a connection to an interruption of time in a city that now, after reunification, is still finding its footing.

The year is 2004, fifteen years after the fall of the Wall, but its shadow persists; former demarcation lines and vast areas not yet cleansed of their link to a dark past remain. Residents are inclined to point them out to visitors as if sharing the city’s history with a certain wistfulness, while the narrator tends to react to these spaces as if they hold a connection to an interruption of time in a city that now, after reunification, is still finding its footing.

At his first official function, just days after arriving, our protagonist meets Farqul, the self-styled Bangladeshi poet who appoints himself as his guide and guardian during the early weeks of his stay. Their conversations are peppered with snatches of Bangla. A journalist with Deutsche Welle, Farqul is an elusive yet ubiquitous figure—or perhaps, furtive, as the narrator speculates on their first encounter—who is a well-known exile and appears to be well-liked among members of Berlin’s immigrant community. He had emigrated to Germany in 1977, two years after being kicked out of Bangladesh for writing a blasphemous poem. Prior to leaving India he had spent a rather fractious interlude among the literati in Calcutta where he met and was apparently aided in his move to Berlin by none other than Gunther Grass. (The narrator simply conveys this information without question.) He is a generous, if eccentric, host. He not only shows the narrator around, but helps him get outfitted for the coming cold weather.

Farqul – in the excitement of being in your company – was a man who liked to share. He gave you food; he stood next to you in solidarity when you tried on jackets; he would have shared cigarettes and his flat if I’d been a smoker or needed a room; he might offer his woman. He didn’t create a boundary round himself, saying, ‘This is mine; not yours.’ As long as he was with you he was in a state of transport.

Yet when Farqul suddenly disappears without notice, the narrator flounders a little. Most of the acquaintances he makes through the university remain casual, but he does have the hint of an affair with a German woman who unexpectedly reaches out to him after having attended his inaugural lecture. She tells him she loves India (“I’m wary of Europeans who ‘love’ India – an old neurosis”) and their liaison, for what it’s worth, develops rather uncertainly. The narrator is often uneasy; he seems to be unwilling to exercise any agency. Rather, he tends to drift without commitment. As a result, those who come into his life with whom he may have grounds for connection—social, academic, romantic—have to be persistent if any kind of relationship is going to develop.

He also, for some reason, maintains a distance from the German language. His housekeeper speaks no English and the simple German phrases she uses with him he claims to understand only through her accompanying gestures. He seems content to exist in the city without being able to interpret the conversations around him—to revel in the meaning conveyed by the music of the language rather than its vocabulary or grammar:

They go on about the rebarbative sound German makes, but individual words and names have greater beauty – more history – than English can carry. I entered Hackescher Markt in my mind’s eye five or ten minutes before reaching there. ‘Friedrichstrasse’ had come up in a dream recently, as a port of arrival. Kristallnacht was transparent, broken. I woke up to words and didn’t bother with the language.

Certainly his sojourn in the city is necessarily brief, but his passivity is notable, as is his unwillingness to acknowledge how unmoored he is. That is, until he begins to become disoriented and experience blackouts. The narrative becomes more fragmented as he loses himself navigating an unfolding layout of streets and network of train stations:

The trains emanate sorrow. Not like humans. The humans, in fact, are distracted and impatient. The trains aren’t alive in the way we understand the word. But they feel.

Domination of steel: steel smoke, steel sky.

This book has an intentionally unfinished feel owing to the fact that the narrator’s own mental state seems to be unravelling as his time in the city nears an end. We learn little about his earlier life because he admittedly feels disconnected from it himself, making for a mysterious, yet beautifully written tale of one man’s estranged sojourn in Berlin.

Sojourn by Amit Chaudhuri is published by New York Review Books.