That day was a little bit odd. After walking down the street

. I stopped in a movement,

at one particular moment of growing older.

And I sensed it (the moment of growing older) like a scientist

. over a microscope:

the precise split-second border between the former and the

. future me.

In that borderline, tangible second, I was nothing; only an echo

of a former self and the germ of the future, the old me.It lasted for only that one moment. Then the air rustled like

. golden hay

and into the street a horse came.(from “A Horse Came Into Our Street”)

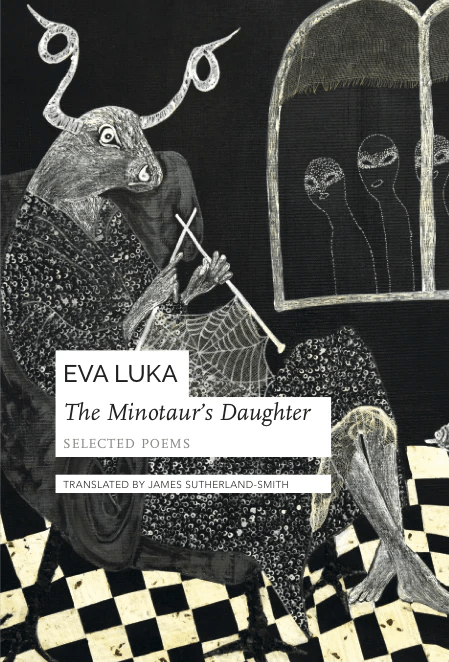

Odd is one way to describe the poetry of Slovakian poet Eva Luka—deliciously, devilishly, delightfully odd. Her poems open up strange, shimmering vistas filled with fantastic imagery. Born Eva Lukáčová in Trnava, Slovakia, in 1965, she studied English and Japanese, first in Slovakia and later in Japan. She began publishing poetry under her given name, first in anthologies and then, in 1999, with her first collection Divosestra (Wildsister). For her second book, Diabloň (Deviltree), published in 2005, she adopted her nom de plume, along with what would become her practice of selecting a poem from each collection to provide the title for the work to follow. In this way, her poems speak to one another within and across collections which also include Havranjel (Ravenangel, 2011) and Jazver (I-Beast, 2019).

With The Minotaur’s Daughter, translated by James Sutherland-Smith, a selection of poetry drawn from her work to date, is now available in English for the first time. In his Afterword, Sutherland-Smith suggests that Lukáčová may be one of the last great poets of resistance in Europe, citing her:

With The Minotaur’s Daughter, translated by James Sutherland-Smith, a selection of poetry drawn from her work to date, is now available in English for the first time. In his Afterword, Sutherland-Smith suggests that Lukáčová may be one of the last great poets of resistance in Europe, citing her:

resistance to conform artistically and [a] resilience against the potential psychological pressures resulting from the circumstances of her life and times. Eva’s resistance to conform to being categorized within a specific poetic movement—particularly those associated with a single gender—reflects the individual nature of her work, and this artistic independence even challenges gender identity in the personae that inhabit her poems.

A transgressive spirit illuminates her poetry, extending beyond matters of gender, to explore questions of personal freedom, sexuality, and desire within a phantasmagorical landscape featuring eccentric figures, mythical creatures, and fabulous flora and fauna. She creates, with her poems, haunting, often dark, scenes or vignettes that can be as intriguing as they are disarming.

Unlike many similar selections that draw from across a poet’s oeuvre, the fifty-nine poems that comprise The Minotaur’s Daughter are not presented chronologically, or divided according to the individual volumes they come from. Rather, the assortment seems to be loosely thematic, with many of the earlier poems coming from more recent collections, and some of the Japanese inspired work from her first book coming later. And, because she sometimes writes companion pieces that appear one or two volumes apart—for example, “Wildsister,” the title poem from her first book, is later answered with “Wildbrother” in her third—here they are presented together. The impact is more powerful this way. It is also evident that Luka appreciates the poetic storytelling potential of triptychs and series, something that may have developed over time, as Sutherland-Smith seems to think that her upcoming fifth collection may include even more.

One of the most developed sequences in this selection begins with an ekphrastic poem inspired by Leonora Carrington’s painting Portrait of the Late Mrs Partridge. In this piece, the speaker is the artist commissioned to capture the likeness of the wild-haired woman in her odd partridge skirt. He then becomes famous, but is ever haunted by the painting. Four more “Late Mrs Partridge” poems follow, addressing her body, her death, her husband, and finally her wake. Mrs Partridge herself voices all but her husband’s lament from beyond this life, even returning to her own wake, still nursing an internal flame, to drink a toast with the bereaved:

A man sits at the top table, his face,

wrinkled from the tertiary era, with an incalculable expression.

The atmosphere is gloomy, but still audible

is a ubiquitous slurping, gurgling and belching,

as if the whispered stories haven’t had as much power

as unstoppable bodily hunger and thirst.

Leonora Carrington’s eerie, fantastic paintings appear again as the stimulus for five other poems in this translation (not to mention the poet’s own artwork which graces the cover). At times, Luka stands as an observer, as in “And Then They Saw the Minotaur’s Daughter” where she watches the “two well-behaved boys—somewhere between childhood and doubt” watching the noble horned woman-creature while spirit-like forms fill the room, Elsewhere she animates and engages directly with the scene, even imagining the central figure outside their fixed setting as in the Mrs Partridge quintet and “Necromancer,” a poem after the abstracted, surreal painting of the same name.

The images that dominate Luka’s poetry are drawn from nature—water, flowers, birds, reptiles, and animals—but, as with her human beings, the line between the real and the spiritual is fluid. They inhabit a shifting borderland and there is a pagan, pantheistic sensibility at play. Her animals inspire awe and fear, mythological figures speak, and a woman invites an angelic black bird (Ravenangel) into her bed in a dark sequence of desire, longing, and loss. Hers is a magical world, albeit one that accepts that mystery can be tinged with heaviness and pain. But it is not a relentlessly dark place; rather it exists in a kind of intermediate, and yet, ultimately familiar, space:

It’s incomprehensible, that border of yours

between the feverish night and the healing morning; as if you

. didn’t recognize

the differences between frenzied hyacinths and tamed hyenas.

. What you tell me

in the evening, no longer applies in the morning, and vice versa(from “You and Me When the Cock Crows”)

One might describe the poetry of Eva Luka as akin to richly woven tapestries; the vignettes she crafts are vivid, often disturbing, but they tend to close with a note of promise, that is, with a measure of the resilience that characterizes her work. This quality is evident in The Minotaur’s Daughter. Her striking imagery is well captured in Sutherland-Smith’s translations, while his decision to break with the typical chronological ordering of a “selected poems” collection offers her first English language readers a deeply rewarding introduction to her singular poetic universe.

The Minotaur’s Daughter: Selected Poems by Eva Luka is translated from the Slovak by James Sutherland-Smith and published by Seagull Books.