I grab the neck of a dinosaur with long lashes and the hand of a small boy with dark-chocolate eyes, put them both in the car, half my body engulfed by the back seat, torso twisted, fingers straining to reach, and then fasten the seatbelt. I put a multicoloured backpack containing a lunch in a plastic box, a bag of chips, a bottle of water, a change of clothes, size 5T, on the seat beside them. Then I walk back around the car, keys bouncing against my palm, sit down behind the wheel, and start the car. First Tuesday in December, mid-1990s, it’s 8:30 a.m., bitterly cold, and blue is the colour of the sky.

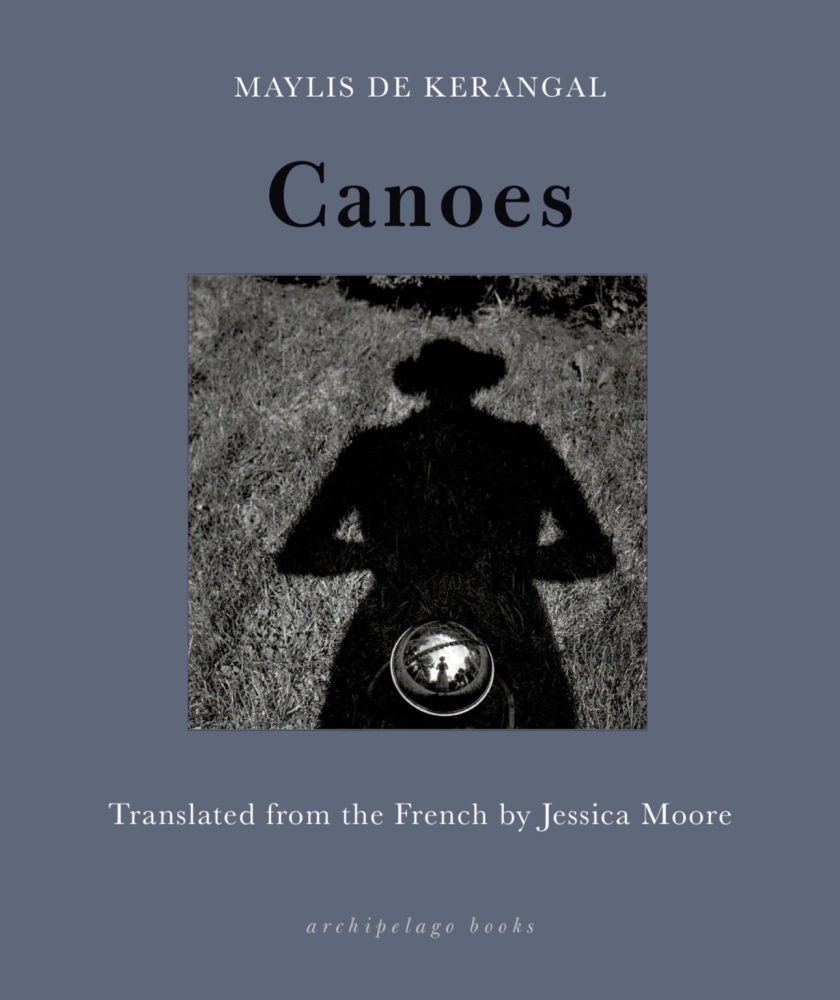

This is the opening of the novella “Mustangs,” the centrepiece of Maylis de Kerangal’s collection Canoes. It’s a precise description of a routine series of actions, but then, in the French writer’s fiction, the seemingly ordinary moment can contain multitudes and what begins quiet and lowkey, can turn unexpectedly, toward an ending suspended in possibility. Her ability to balance emotional restraint against an exceptional eye for detail, and a fondness for sweeping sentences and paragraphs that frequently go on for pages, allow her to tell stories that are at once spare and revealing. She knows just where to turn her narrators’ attention as their stories unfold.

The pieces in this volume—seven short stories and one novella—are connected by a common theme and by a singular image. The theme is “voice.” From a story about a woman consciously trying to lower her voice to advance her career in broadcasting, to the tale of a father reluctant to remove his dead wife’s recorded greeting from the family answering machine, voices—changed, analyzed, unleashed, unexpected—feature directly or indirectly throughout. Translator Jessica Moore indicates in her Note that de Kerangal began working on this collection just as mask mandates “caused mouths to disappear,” something that also often altered sound and auditory comprehension, and may have contributed to this thematic link. But the distinct image or motif that recurs in each of these very different stories seems much more random and therefore a is little treat each time it makes an appearance. The “canoe” of the collection’s title only appears in any particular detail in one of the stories, otherwise it might be a pendant, a craft observed in the distance, or mentioned in some other passing context. A nice, fun touch.

The pieces in this volume—seven short stories and one novella—are connected by a common theme and by a singular image. The theme is “voice.” From a story about a woman consciously trying to lower her voice to advance her career in broadcasting, to the tale of a father reluctant to remove his dead wife’s recorded greeting from the family answering machine, voices—changed, analyzed, unleashed, unexpected—feature directly or indirectly throughout. Translator Jessica Moore indicates in her Note that de Kerangal began working on this collection just as mask mandates “caused mouths to disappear,” something that also often altered sound and auditory comprehension, and may have contributed to this thematic link. But the distinct image or motif that recurs in each of these very different stories seems much more random and therefore a is little treat each time it makes an appearance. The “canoe” of the collection’s title only appears in any particular detail in one of the stories, otherwise it might be a pendant, a craft observed in the distance, or mentioned in some other passing context. A nice, fun touch.

As one might expect, the extended piece, “Mustang,” anchors the collection. The unnamed narrator is a French woman who is living with her husband and young son (whom she simply calls Kid) in Golden, Colorado. Sam is taking a course at the School of Mining where he is quickly adapting to American life and language, while she struggles to find her footing in this vast suburban community in the foothills of the Rockies. At first walking suffices, but the lack of the kind of integrated train and transit system of a European city soon leaves her frustrated, as does the lack of purpose and work to fill her now empty days. So her husband, who has actually arranged this short term foreign escape more for her sake than his own, suggests she learn to drive. He buys a used Mustang and she gets her license. Funny, bittersweet, and ultimately terrifying, this is wonderful story of a woman seeking to redefine herself after loss in a mythic Western landscape of cowboys and dinosaurs.

By contrast, each of the other much shorter stories are condensed, finely drawn episodes that reveal something, often unsettling, of their narrator’s life or engagement with others, yet leaving much unsaid or unresolved. One of the best, perhaps, is the final tale, “Arianspace.” The narrator is a ufologist—an investigator of UFO sightings. She has been sent to visit a ninety-two year-old woman living along among mostly abandoned homes in a rural area. From her earliest impressions, the researcher can tell that she facing someone special:

I had imagined her small and wizened, the wrinkled skin of an old fig, hair sparse, body brittle and slow, an apron tied around her waist and black peasant stockings, but she was something else: a tall, regal woman in jeans, a red T-shirt, and boots, and she was thin, long grey hair over her shoulder, cheekbones still high, and beneath ragged eyelids, eyes of a deep black – the kind of black that absorbs nearly all visible light, and which is found in bird of paradise feathers or on the belly of peacock spiders; altogether wizened, dry, and flaking, but conveying a great impression of physical strength and brutality.

Indeed, not only is Ariane a no nonsense woman with a firm commitment to the alien phenomena she observed, she has impressive evidence. . .

With short story collections, especially dedicated volumes like this as opposed to larger compilations, a test of success can lie in the degree to which each entry stands apart from the others. Even though some of these pieces have a very tight focus, the characters and narrative voices (all first person), are distinct, the settings varied, and in some instances I was left with this eerie feeling—a sense that I wanted to know where the characters went after the story closed, a what-happened-next sort of thing. That is for some readers a negative to the shorter forms, but especially with a writer like Maylis de Kerangal, who is unafraid to leave an open door, the extended possibilities only make the situations she depicts seem more real.

Canoes by Maylis de Kerangal is translated from the French by Jessica Moore and published in North America by Archipelago and MacLehose Press in the UK.