Was it something in the air? In the history of the seaside town? Providence, Rhode Island in the mid-nineteenth century was, this curious biography assures us, famous for its abundance of unsettled spirits:

It is true that other towns also have their ghosts — nowhere, however, are they so noisy and restless. So many phantoms live in Providence they fill up every nook and cranny. Saturated with their breath, the air grows oppressive and causes headaches. You don’t so much walk down the streets as fight your way through invisible throngs.

(from “The Female Presence”)

And a plethora of phantoms makes it easier for a medium to conduct a séance that will satisfy the spiritualists gathered in her parlour. For an attentive and innovative medium like Phoebe Hicks, a successful séance was almost guaranteed, night after night.

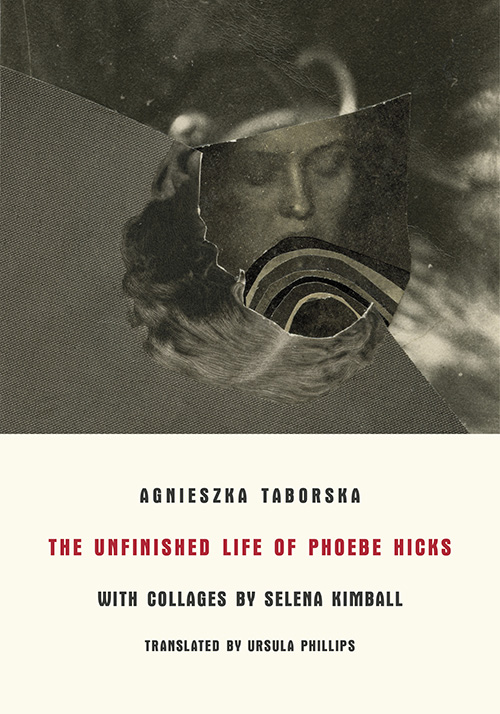

Her story, and that of the rise of Spiritualism in America, unfolds through a series of episodes recorded by Polish writer Agnieszka Taborska, and paired with stunning collages by Selena Kimball, in The Unfinished Life of Phoebe Hicks, new from the inimitable Twisted Spoon Press. If it seems odd that Taborska, an art historian specializing in French Surrealism has chosen to turn her attention to Rhode Island and placed her fictional heroine there, it shouldn’t be. She divides her time between Warsaw and Providence, and her affection for the town and its ghostly history comes through in this imaginative biographical endeavour.

Her story, and that of the rise of Spiritualism in America, unfolds through a series of episodes recorded by Polish writer Agnieszka Taborska, and paired with stunning collages by Selena Kimball, in The Unfinished Life of Phoebe Hicks, new from the inimitable Twisted Spoon Press. If it seems odd that Taborska, an art historian specializing in French Surrealism has chosen to turn her attention to Rhode Island and placed her fictional heroine there, it shouldn’t be. She divides her time between Warsaw and Providence, and her affection for the town and its ghostly history comes through in this imaginative biographical endeavour.

Phoebe Hicks, medium extraordinaire, stumbled into her unlikely profession through the most peculiar circumstances. On November 1, 1847, she found herself violently ill with a bout of food poisoning triggered by a meal of clam fritters. Were it not for a nosey photographer who happened to peer into her window and catch her vomiting into the bowl on her washstand, the incident would have passed into Phoebe’s feverish memory and stayed there. But instead, the invasive images—coincidentally captured with a recently patented photographic method that allowed for an exposure of only three minutes—would be reproduced and widely interpreted as evidence of ectoplasm spewing from her mouth. Although ectoplasm, the manifestation of spiritual matter, would not be officially described until 1894, Phoebe would prove to be ahead of the curve in so many ways—so far ahead in fact that she would even entertain the ghost of Harry Houdini years before his birth—but for some reason her notable achievements have fallen from the records of the history of Spiritualism.

This book aims to rectify that oversight.

Phoebe’s first séance was awkward, but she quickly learned from her mistakes and as her gatherings grew in sophistication, her fame spread. Of course, as the interest in séances increased, so did the number of practitioners, both sincere and false. Yet, as ever, Phoebe was a class act. Her guests would be greeted by the cook’s son, and then ushered into the parlour by her maid, Miriam, a woman so dignified in manner and appearance that some would mistake her for the mistress. Others, however, mused that she may have been the true secret to Phoebe’s success.

They accused her of practices employed by accomplices of other mediums to gain information about clients: bribing servants, placing “their people” in noisy inns where alcohol loosened tongues, studying gravestones — the most reliable sources of information about family relationships. They forgot that it sufficed to reside in Providence a little while to know enough about one’s neighbours to imagine the rest. For the inhabitants of the magic town were strangely alike.

(from “The Maid”)

Now, Phoebe was not content to simply summon the spirits of the locally departed, she also welcomed figures from history, and is reported to have performed a number of impressive feats during the course of her gatherings. But more critically, she established standards for the practice of conducting séances, strengthening the acceptance of the role of medium. For not only was Spiritualism a practice that held particular appeal for women, the profession of medium offered some of these same women an opportunity to support themselves outside of the traditional bonds of marriage. And for some that was a very worrying trend:

A few ill-disposed doctors claimed that Spiritualism was no more than a safety valve for madness and old-maidenhood, that participation in séances was conducive to hallucinations, that the fashion for the table turning, spreading at dizzying speeds, was responsible for madhouses bursting at the seams, that instead of a parlour with its round table a more fitting place for mediums was a hospital isolation ward.

(from “Something That Might Be Called Hysteria”)

Behind the accusations of madness, of course, lay the fear that in the communion with spirits might lead to emancipation.

Twisted Spoon publishes some of the most delightfully strange books and The Unfinished Life of Phoebe Hicks is no exception. Presented as a serious account—albeit with a healthy amount of wry humour—of the role of this somewhat mysterious medium in the early years of spiritualist practice, the portrait that emerges is of a woman for whom the boundary between the world of the spirit and the world of the flesh has become somewhat permeable. She ultimately disappears, not only from history, but from the town of Providence itself, her final whereabouts unknown. But the insinuation is that, unlike the many impostors and charlatans who flocked to the profession in its heyday, there was something uncanny about Phoebe. Something wise, practical, and well, just possibly, genuine. . .

The Unfinished Life of Phoebe Hicks by Agnieszka Taborska with illustrations by Selena Kimball is translated from the Polish by Ursula Phillips and published by Twisted Spoon Press. It is available now in the UK and Europe, and will be released in November 2024 in North America.