To the young, because they are young, everything looks bigger, taking on proportions relative to their age and to the space their bodies occupy, amidst other bodies heavier, taller, and broader than theirs. The tallest person is the oldest, and the uncle or aunt who has reached the age of thirty is of such an advanced age that it is difficult to grasp the concept of this “thirty,” based on the five fingers, or even ten, that the child will hold out to indicate his age. As for the grandfather or grandmother, that’s another story, combining reality and fantasy, the perceptible and the obscure, for the stories they tell of the past place them between two worlds, one foot here and the other there, with this mysterious “there” reaching into a past of which God alone knows the beginning and the end.

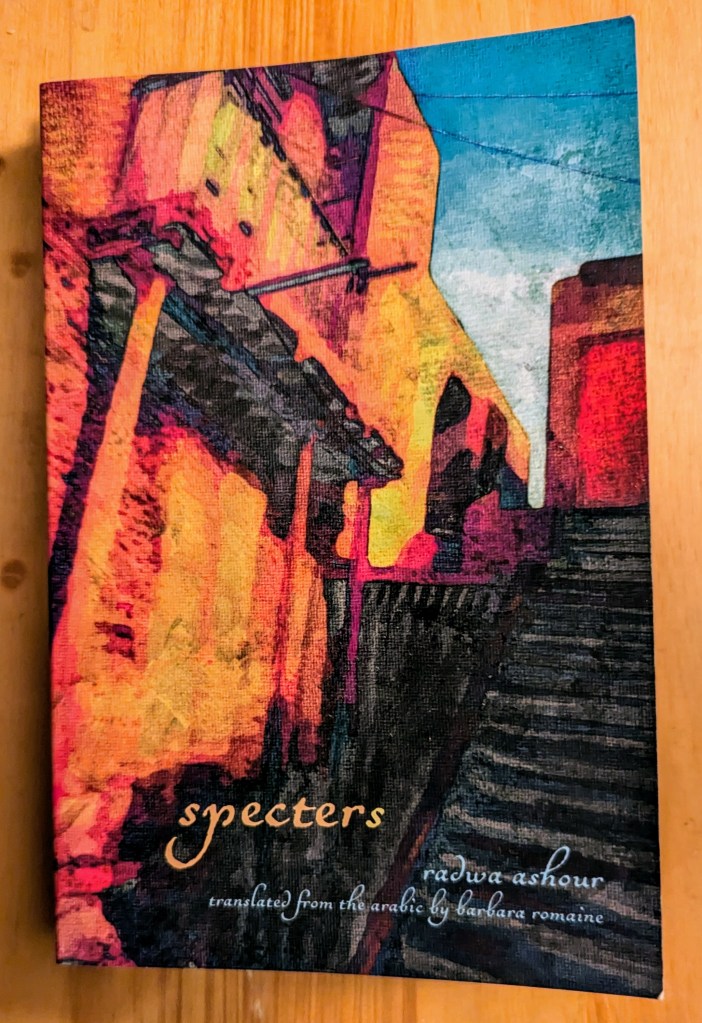

Scepters, by Egyptian novelist and academic Radwa Ashour, is a work that is ever seeking to place itself in relation to time and place, history and memoir, fiction and metafiction. Complex, multilayered, and dynamic, it explores the many ways truths can be approached, examined, and understood. This novel opens with the portrait of Shagar, a strong-willed woman, widowed young, who refused to remarry, raised three children on her own and became the matriarch of her community with, later in life, an uncanny ability to hear the voices of ghosts. The story then turns to her great granddaughter, and namesake, whose unusual appellation (meaning “tree”) was given at the insistence of her grandfather despite strong opposition in the family. As such, the name would align her with her paternal grandfather whose “inexhaustible supply of stories” would have a significant and lasting influence on her life.

But then, the narrative voice shifts. Radwa, the author, enters and immediately raises questions:

But then, the narrative voice shifts. Radwa, the author, enters and immediately raises questions:

What happened? Why did I leap so suddenly from Shagar the child to middle-aged Shagar? I reread what I have written, mull it over, stare at the lighted screen, and wonder whether I should continue the story of young Shagar, or return to her great grandmother, or trace the path of her descendants to arrive, once again, at the grandchild. And the ghosts—should I consign them to marginal obscurity, leaving them to hover on the periphery of the text, or admit them fully and elucidate some of their stories?

She considers erasing what she’s written and starting over with her own story. She then debates whether she should keep Shagar and interweave two separate stories into one. “Who is Shagar?” she asks. Before the chapter is out, Shagar, the now fifty year-old professor of history is back. But not for long.

Moving between memoir, novel-in-progress, metafictional asides, and historical research, Scepters tells the story of two women born on the same day, growing up in Cairo on opposite sides of the Nile. One will become a novelist, the other an historian writing a book called The Scepters about the 1948 massacre at Deir Yassin in Palestine. They will attend the same university, and become involved to varying degrees with the student protests of the 1970s and 80s. However, although both author and character share birthdates and professions, if in different disciplines, and are writing books with similar names, this is not autofiction, nor is Shagar an alter ego. Shagar remains single and much of her story reflects her need to find meaning through political action, and through the lives of her students and a young boy who lives next door. There is an inherent emptiness that she will not find an answer to until the close of the novel. Radwa, by contrast, marries Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti, exiled from his native country in 1967, and then deported from Egypt ten years later when their son Tamim is an infant. Much of her personal story recounts the complications—emotional, practical, and bureaucratic—of trying to maintain family life divided between countries during the precious time afforded by summer and holiday breaks. As such, it is a vital and deeply personal complement to Barghouti’s own account of the same period in his moving memoir I Saw Ramallah.

Generally, the fictional and nonfiction streams that comprise Specters unfold in alternating chapters, one or two at a time. Shagar’s academic life, as a student and as a professor, is central to her story. As is her often disruptive existence within the academic environment. She is political, active in protests, and will spend time in prison, briefly during her graduate years and again later. It is something that she does not necessarily see as a negative:

In September 1981, when she was dismissed from the university, she didn’t panic; after all, she was no longer under pressure to write a thesis or dissertation. There was nothing in the decision that threatened a transformation in the course of her life.

In prison there was ample time to consider the particulars of a life dispersed randomly in the press of daily concerns. In prison there is time, because the days and the nights as well, take their time: each hour has its own sphere, through which she passes in stoic endurance, and into which the succeeding hour does not crowd. Perseverant, country hours that know none of that feverish haste, the constantly ringing telephone, or the harried pushing and shoving in the city’s streets and its overflowing buses, its chaotic rhythms.

Shagar is determined, self-reliant, but not without doubts. About her students, and about changes she observes in the youth. The motivation to political protest of her own younger years now seems to pull promising young people to more radical and dangerous pursuits. Eventually she will turn her attention fully to her research and the subject she has wanted to explore since she first switched from ancient to modern history in the final year of undergrad studies: the massacre at Deir Yassin.

Shagar’s story naturally contains more direct historical and documentary materials—from the notebook filled with reflection her grandfather leaves her to testimonials of survivors of the massacre. But of course, the research is ultimately Radwa’s, a fact that leads at one point to a discussion of her approach to writing her well-known historical novel set in late fifteenth century Granada. This is but one of many places in which the lines between memoir and fiction are openly crossed. Shagar is someone she sometimes loses track of and she finds herself wondering what Shagar is up to or what she would think about something. The explicit and playful metafictional element of this inventive novel within a memoir (or is it a memoir within a novel?) is not only essential to its coherency, but the key to its richness and depth. Blurring the boundaries between the personal and the political—witnessed in Shagar’s life as much as in Radwa’s—highlights the inability to separate the creative process from the research involved or the characters created. Yet, set against the backdrop of ongoing protest, conflict, and instability—in Egypt, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, and Iraq—real lives can only find so much anonymity through fiction. The memoirist can chose what and how much she wishes to reveal, whereas for the documentarian, truths, especially the voices of survivors of violence, must be respected and preserved as faithfully as possible. These are the sorts of concerns Radwa Ashour seeks to balance in Specters. Where one life lived ends and another imagined begins cannot be clearly defined with a simple shift from first to third person, for such shifts occur, on occasion, within each thread, but at the end of the day, one is left to wonder if it is ultimately through the lens of fiction that ghosts can ever truly be heard.

Specters by Radwa Ashour is translated from the Arabic by Barbara Romaine and published by Interlink Books.