Some novels greet you at the door—or in this case, just beyond the baggage claim—engage your attention, and hold you, sentence by sentence, through the past and the present, until you reach your final destination. If You Kept a Record of Sins, by Italian writer Andrea Bajani, is such a book. Yet the magic of this story lies entirely in the telling—in the delicate balancing of select, sharply depicted images within a spare, measured narrative that simmers with barely restrained emotional tension. On the surface, it’s the tale of a young man grieving his mother’s legacy of repeated departures and arrivals, the mainstay of his childhood, while he attends to her final dispatch in Romania, the ultimate faraway destination from which she would never return. His prospect of achieving closure, however, is tenuous for beneath the surface, complex and conflicted feelings remain unresolved.

The novel opens with Lorenzo’s arrival in Bucharest and his initial contact with Christian, the driver who will serve as his guide to the city and his means to understanding some elements of his mother’s life. Although she is dead, she is never far away—Lorenzo’s account is essentially directed toward her—but his tone speaks to an unbreachable distance. After enough time, absence no longer to makes the heart grow stronger. Addressing her is perhaps the only way to make sense of his loss:

The novel opens with Lorenzo’s arrival in Bucharest and his initial contact with Christian, the driver who will serve as his guide to the city and his means to understanding some elements of his mother’s life. Although she is dead, she is never far away—Lorenzo’s account is essentially directed toward her—but his tone speaks to an unbreachable distance. After enough time, absence no longer to makes the heart grow stronger. Addressing her is perhaps the only way to make sense of his loss:

You started leaving when I was young. The first trip was for pleasure, to go meet some friends who were off trying to strike it rich. You drew the world on a sheet of paper the night before, to show me where you were going. We’re here, you said, and tomorrow I’ll be right down here, in this spot. You drew a line with a red marker from home to there. It’s a bridge, you said, it’s like crossing the river to the other side. And under the bridge we colored everything blue; we filled in the water of Europe. Then we taped the picture to the refrigerator, and that’s where it stayed for years to come.

His mother’s trips became more frequent. Promotion of her egg-shaped, sweat-inducing weight loss machine takes her around the world. The souvenirs she brings home multiply in her son’s room, mapping her absence. When she is home, the increasing presence of her business partner in her life begins to put a strain on her marriage. Before long, the partner and the promise Romania holds as the ideal base for their enterprise is too strong and finally she is gone for good. Left behind in Italy, Lorenzo and his dad will never see her again; even the phone calls will dwindle as the years pass.

Now grown and finally in Romania himself, Lorenzo is reunited with Anselmi, his mother’s business partner, a loud, brash Italian who has clearly found a level of success and self-importance that would have eluded him at home. He is of a breed, not uncommon in the country—latter-day middle-aged foreign opportunists—and Lorenzo will encounter more than a few men of this type, including another long-time friend of his mother who reveals to him the shocking and sorry state of her final years. No one is exactly forthcoming with details, but Anselmi has taken up with a young Romanian woman named Monica who seems less than thrilled with her circumstances and rather attracted to the young Italian she has been ordered to attend to. Lorenzo, however, is seemingly most comfortable in the company of Christian, his mother’s long time driver. With him he is able to be present without pressure. Together they visit Ceausescu Palace, spend time in the city, share both laughter and silence. Lorenzo is gently attentive to the hidden strengths Christian seems to carry, leaving a faint erotic tension in the air.

If You Kept a Record of Sins offers an account that rides as much on what is unspoken as on what is shared. The narrative is economical and precise, moving from one finely honed image to another. Lorenzo’s mood is lonely, detached. He is cautious in his engagement with others. The abandonment he felt at a young age comes through even as he recalls tender moments of play or adventure with his mother. As an adult he appears to be grasping at something to feel for someone he hardly ever knew. Her own family, he is aware, were oddly unforgiving and remote themselves, while her final years in Romania were marked by romantic betrayal and self-destruction, but how to make sense of the damage she was responsible for between those two ends? A mixture of love and ambivalence fuels this bereaved son’s ongoing one-sided conversation with this mother as, for example, in this account of his first night in her apartment:

The mirror was too low—it cut off my head—and to think there was a time you used to lift me up, to look into my eyes. I was still wet when I left the bathroom, a trail of droplets behind me. I turned off all the lights, except the nightstand lamp. I took my pajamas from my bag, put them on, and went over to your bed. I dropped onto it, tried to bounce, then slipped under the covers. And it was almost as if I felt your bones, under there, that I was lying between bone and muscle and had to stay very still, or else I’d hurt you.

This is a novel at once sombre and hopeful. Beautifully translated by Elizabeth Harris, it never falls in to oversentimentality. Grief is idiosyncratic, sometimes elusive, and Bajani captures this complexity well. The cast of complicated secondary characters add depth to Lorenzo’s experiences without ever distracting or weighing them down. Reading fiction this well-crafted is a joy.

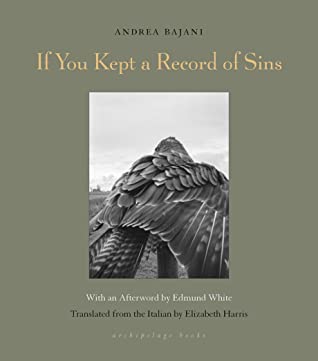

If You Kept a Record of Sins, by Andrea Bajani is translated from the Italian by Elizabeth Harris and published by Archipelago Books.

There’s so much sentimentality attached to motherhood, it’s very difficult when the relationship is fraught.

Yet mothers are just the same as everyone else, and some of them inevitably are flawed human beings. Learning to accept parents as they are is one of the tests of adulthood IMO.

LikeLike

I love Archipelago Books. It doesn’t seem to matter what they’re about, the way they describe them makes them seem urgently important and, often, beautiful. I had to read that bit about the mirror twice to visualize it and then it brought back the opposite positioning of how long it took to be TALL enough to see oneself wholly in the mirror!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I fell in love with the title and cover and bought it on those terms. I was not disappointed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, thank you for writing this review! I loved reading it and feeling like there was someone out there who shared my experience and took from this beautiful book the same things I did. I’ve read it a couple times since it came out, and no book has ever affected me so strongly. I’ve been looking for others like it to no avail (with the exception of maybe The End of Loneliness by Benedict Wells, which I’d read before it), so I wondered if in your reading you’ve come across anything comparable?

Thank you again,

S.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not very good at recommending similar reading experiences. This book is definitely the kind of thing I tend to like best—very spare, leaving a lot unsaid. At the moment I am recovering from a broken leg and somehow it seems to have slowed my thinking! Have you ever read Fleur Jaeggy? She’s a Swiss writer who writes in Italian and you might like Sweet Days of Discipline or SS Proleterka. Just a thought.

LikeLike