Maybe at twenty-six he was already too old to seriously go about becoming a poet.

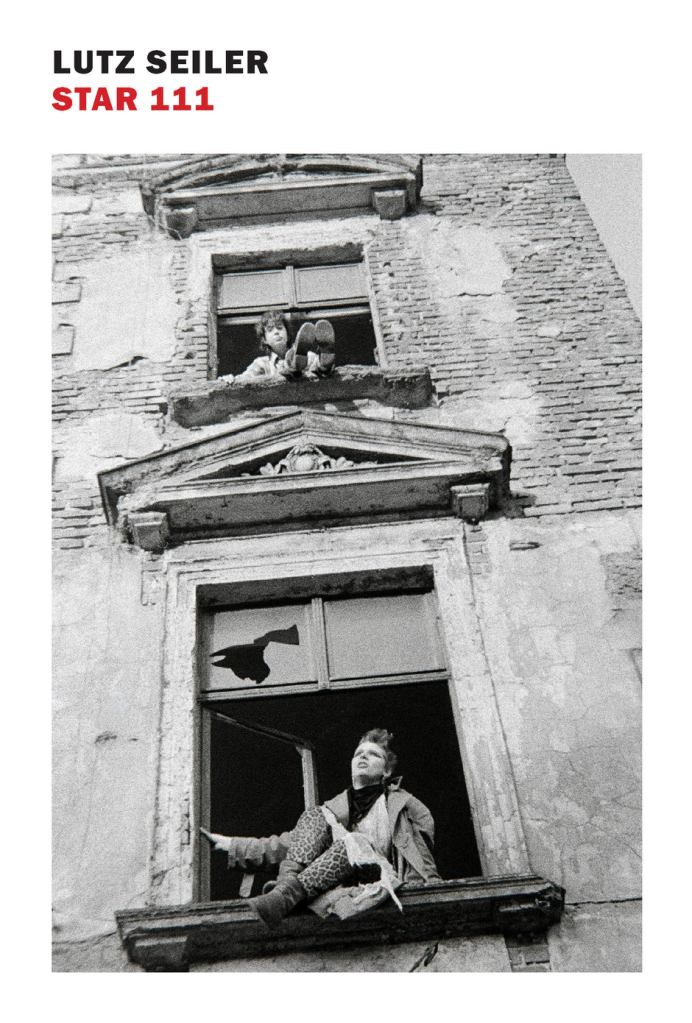

The fall of the German Democratic Republic was rapid and unexpected. As other communist regimes in Eastern Europe began to disintegrate, the East German government tried to maintain control, but in early November 1989 a mistaken announcement led to the sudden opening of border crossings through which hundreds of thousands of East German residents would soon pass. This is where Star 111 by German poet and writer Lutz Seiler begins.

Twenty-six year old Carl Bischoff has just been summoned from Leipzig to his home town Gera in the state of Thuringia. The telegram, dated November 10, reads “we need help please do come immediately,” but as he waits for the train, he has no inclination that all the childhood securities he once imagined were unassailable are about to be upended. His parents, Inge and Walter (Carl has long addressed them by their first names), waste no time announcing their intentions. They are going to take advantage of the crumbling state of the GDR and cross the border. Now. This is, they tell him, a dream they have long held and, should the precious opportunity be short lived, they plan to leave promptly. They will head for the refugee camp at Giessen, and then split up to better their chances of finding suitable lodgings and employment on the other side. Carl’s assignment is to stay behind and look after the apartment. He will be the rearguard. But left behind, Carl finds he is at a loss, confused by this sudden inversion of what he imagines the parent-child dynamic should be and worried about his middle-aged parents who by rights should be the ones at home worrying about him.

Twenty-six year old Carl Bischoff has just been summoned from Leipzig to his home town Gera in the state of Thuringia. The telegram, dated November 10, reads “we need help please do come immediately,” but as he waits for the train, he has no inclination that all the childhood securities he once imagined were unassailable are about to be upended. His parents, Inge and Walter (Carl has long addressed them by their first names), waste no time announcing their intentions. They are going to take advantage of the crumbling state of the GDR and cross the border. Now. This is, they tell him, a dream they have long held and, should the precious opportunity be short lived, they plan to leave promptly. They will head for the refugee camp at Giessen, and then split up to better their chances of finding suitable lodgings and employment on the other side. Carl’s assignment is to stay behind and look after the apartment. He will be the rearguard. But left behind, Carl finds he is at a loss, confused by this sudden inversion of what he imagines the parent-child dynamic should be and worried about his middle-aged parents who by rights should be the ones at home worrying about him.

His age is critical. Carl will repeatedly question what it means to be in his mid-twenties as if there’s some kind of high-watermark that he’s worried he has already missed. He has completed military service, learned a trade, and spent a few years at college, but he is without direction. His dream is to become a poet. Yet, when he is called home, he is apparently recovering from a breakup and a breakdown—something he alludes to but does not discuss because there’s no time. His parents’ departure is so immediate and unnerving that it entirely usurps whatever crash course he might have been on. But, even if it leaves him temporarily unmoored in a world that is rapidly changing, it does offer him a chance to chart a new direction for himself. After a few weeks in Gera, trying to keep a low profile while working his way through the preserves in the cellar, Carl is beginning to bottom out. So he loads up his father’s beloved Zhiguli with tools, a sleeping bag, and some provisions, and heads to Berlin. He has no particular destination in mind. He is simply following a fantasy founded on little more than a few poems set in that mythical city, seeking, as he will later describe it, “the passage to a poetic existence.”

Arriving in East Berlin, Carl tries to get his bearings, picks up the odd unofficial taxi fare, and sleeps in his car. But, with winter settling in it’s a bleak—and cold—existence. Before long he falls ill. When, freezing and feverish, he happens to find his way through the rear door of a cinema, he suddenly steps into another world. So to speak. He finds himself in the company of an odd collection of individuals, led, it would appear, by a charismatic man they call the Shepherd—the owner or companion of a goat named Dodo—who nurse him through his illness and welcome him to their breakfast table, impressed in no small part by his car with its trunk full of tools. His tools?

“No, no Zhiguliman, you don’t have to explain anything here. More than a few people are on the move in this freshly liberated city. The whole world is being parcelled up anew these days—but if you’re looking for something permanent. . .”

Carl is not certain what he is looking for, or what something permanent might even mean. If stability cannot be assured in unstable times, he wants whatever it is the handful of men and women around him seem to have—community. And it seems to be on offer:

It was as if he were already part of a pack, as if he were of the same breed. Everything seemed already embedded according to a long-standing plan and leading toward the only logical conclusion. It was a strange feeling. It was the presentiment of a legend (if there is such a thing, thought Carl), on the point of taking him to its profound, all-embracing “once upon a time.”

It is, in fact, just the beginning. He settles into a spartan empty apartment and soon finds a place among a group of misfits, artists, and anarchists who are systematically occupying abandoned buildings, hoping to take advantage of the shifting political and social terrain to craft a kind of anti-capitalist utopia amid the ruins of a damaged urban landscape before others come to reclaim it. His bricklaying skills secure his place.

Over the months that follow, Carl will oversee renovations, begin to work in the Assel, the café the Shepherd sets up, and embark on a romantic relationship with, much to his surprise and naïve delight, a woman from his hometown. Meanwhile, the progress of his parents is revealed regularly, but only insofar as his mother’s letters allow him to it piece together through what is shared, or more critically, what is left unsaid. For months after he had dropped them off at the border, there had been an unsettling silence. Then, once he has relocated to Berlin, the missives begin to arrive, secretly rerouted through the post office in Gera. For a long time Inge and Walter are apart (“separately after Giessen”, as planned), and the latter’s whereabouts are unknown. On her own, Inge proves to be remarkably self-sufficient, working and making social connections until Walter is finally found and the couple are reunited. From that point on, Carl’s father will rely on his computer programming skills to build toward the shared future they envision. Inge’s cryptic comments and idiosyncratic expressions imply that there is a greater game afoot, but Carl is being kept in the dark. But then, many months will pass before he finally confesses that he has abandoned his post as rearguard.

As Carl constructs a life for himself in Berlin, building relationships with others, testing his emotional boundaries, and tracing a regular path through the streets of his dilapidated neighbourhood, one central focus drives his days—the need to write, to dedicate at least some time to poetry. With a little promising feedback, he fantasizes about the day he will publish a book of his own poems. Yet, with all the uncertainty (and opportunity) that a rapidly evolving Germany promises, for Carl writing is a discipline that exists on its own ground away from it all. He is a purist, not a documentarian:

So-called reality and its abundance (“the most exciting times of our lives,” as everyone was claiming)—it would never have occurred to him to write about it, not even in a journal, never mind that he clearly wasn’t in any state to keep a proper journal (with regular entries). The main question was whether or not the next line would work. The next line and its sound preoccupied Carl, not the demise of the country outside his window. If the poem didn’t succeed, then life wouldn’t either.

It’s not an easy path to follow, but it’s one that sustains him when everything falls into place and one that devastates him when life runs off the rail and words fail to come.

Decidedly autobiographical in nature, Star 111 is a tale of self-discovery, a portrait of a young man seeking to define his identity as an adult and as a poet against a backdrop of rapid change when, for a moment, all the old rules have been suspended before inevitably being rewritten and reshaped by capitalist interests. Seiler’s limited third person narrative with its frequent parenthetical refrains and clarifications, captures Carl’s insecurity and self-doubt as he navigates this strange terrain. It also facilitates the integration of a wide range of eccentric characters: members of the Shepherd’s “pack,” his neighbours, co-workers and customers at the Assel, his lover and her young son, and the many people he encounters vicariously through his mother’s regular updates. Essentially, then, this is a novel about family—natal, accidental, and imagined—and the forces that gather to form and inform one’s independent being. The “Star 111” of the title refers to the popular transistor radio that was the centrepiece of Carl’s family life when he was a child. The memories of it that haunt him reflect the strange longing that tends to set upon us when life conspires to force us to accept that not only are we truly grown up (whether or not we feel like it), but that our parents are independent adults too. As Carl spends a lot of time re-evaluating his relationship with Inge and Walter, he will wonder whether he ever really knew them at all. Or they him.

Decidedly autobiographical in nature, Star 111 is a tale of self-discovery, a portrait of a young man seeking to define his identity as an adult and as a poet against a backdrop of rapid change when, for a moment, all the old rules have been suspended before inevitably being rewritten and reshaped by capitalist interests. Seiler’s limited third person narrative with its frequent parenthetical refrains and clarifications, captures Carl’s insecurity and self-doubt as he navigates this strange terrain. It also facilitates the integration of a wide range of eccentric characters: members of the Shepherd’s “pack,” his neighbours, co-workers and customers at the Assel, his lover and her young son, and the many people he encounters vicariously through his mother’s regular updates. Essentially, then, this is a novel about family—natal, accidental, and imagined—and the forces that gather to form and inform one’s independent being. The “Star 111” of the title refers to the popular transistor radio that was the centrepiece of Carl’s family life when he was a child. The memories of it that haunt him reflect the strange longing that tends to set upon us when life conspires to force us to accept that not only are we truly grown up (whether or not we feel like it), but that our parents are independent adults too. As Carl spends a lot of time re-evaluating his relationship with Inge and Walter, he will wonder whether he ever really knew them at all. Or they him.

Lutz Seiler is, of course, like his protagonist, a poet first and foremost. This can be seen in the way his chapter titles are picked up in the text, often in the closing line, but more explicitly in his attention to the sounds and the rhythms of language. Translator Tess Lewis—who also translated his first novel Kruso which she describes as forming a sort of diptych with Star 111—writes in her Afterword of the challenge presented by his “ability to capture the minutiae and texture of a vanished world in rhythmic, lyrical prose.” She pays particular attention to the various registers in the original reflecting the different tenors of West and East German bureaucracy, varying speech patterns associated with social class, and the lines of poetry by a host of other poets that echo through Carl’s imagination. When words with multiple meanings afford the author an onomatopoeic flexibility that cannot be fully replicated, Lewis found she sometimes had to make alternate word choices, knowing the full affect could not always be maintained. This is not a loss noticed in the English reading though. The sense that this is a moment in time that will not last long and will never come again is captured so vividly through Carl’s adventures (and misadventures), not to mention those of his parents, that it feels, above all, like a privilege to be along for the ride.

Star 111 by Lutz Seiler is translated from the German by Tess Lewis and published by New York Review Books in North America and by And Other Stories in the UK.

Great review Joe – this sounds fascinating and I’ll see if I can track it down. A fascinating period of history and to see it covered like this, from the inside, is very appealing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the UK the book has been out from And Other Stories since last last year I think (I’ve added the cover). It was a remarkable time. I’m only three years older than the author, and I was, at the time, married to someone whose parents had fled East Germany in the 1950s, so the fall of the Wall was such an unbelievable event. It’s great to have this kind of on-the-ground perspective.

LikeLiked by 1 person