But do not grieve for me

do not grieve for your lonely

to and fro

My hour has rusted

My poem has left

your beaten track

Do not grieve My young poem

is more deeply kissed by life

Deathly it creeps

over under through me

Poetry is murdered hope.

(from “In the wild loneliness of the mountains” / Light)

Having read most of the poetry of Inger Christensen (1935-2009) that is available in English translation, to return now to her earliest published collections, Light (1962) and Grass (1963) is somewhat like experiencing the formative spirit of a writer who will soon make her mark as an original and experimental literary force. And yet, it is clear in these poems composed in her mid-twenties, that she is already exploring the themes and perspectives that will define her most ambitious—and most popular—poetic works. This is perhaps to be expected because only six years separate the publication of Grass from the release of her monumental 200-plus page book-length cosmic poem Det in 1969 (“It” in English translation, 2006).

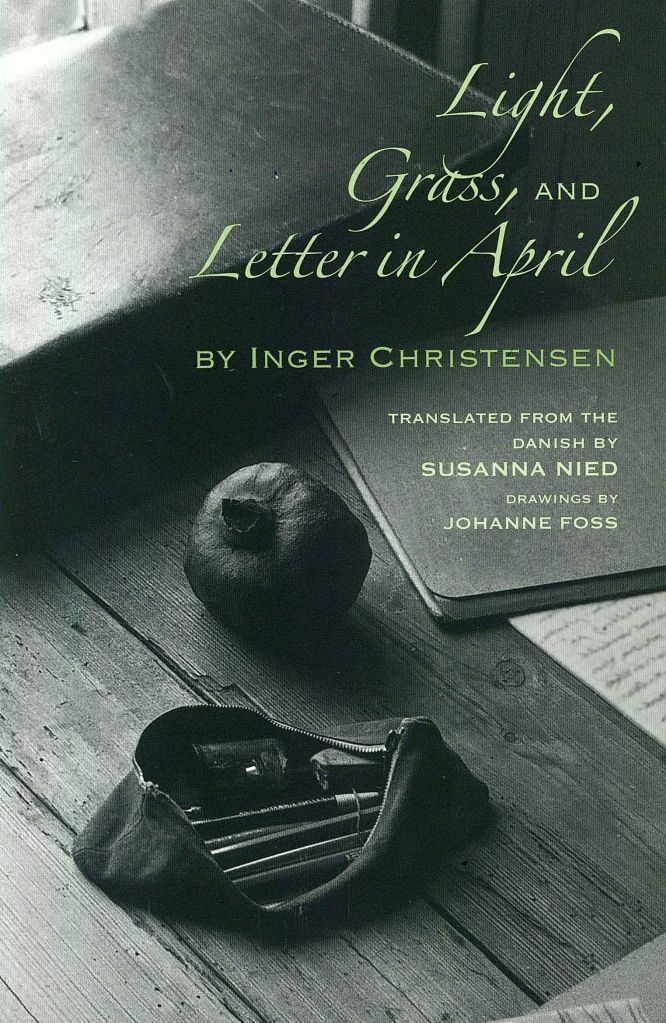

The present volume contains her first two collections, along with her fourth, A Letter in April (1979), a collaborative project that followed ten years after Det. Light and Grass being only one year apart, share much in common and reflect the time in which they were written. Yet as translator Susanna Nied (who has translated all of Christensen’s poetry and is thus well acquainted with her oeuvre) says regarding these two books:

The present volume contains her first two collections, along with her fourth, A Letter in April (1979), a collaborative project that followed ten years after Det. Light and Grass being only one year apart, share much in common and reflect the time in which they were written. Yet as translator Susanna Nied (who has translated all of Christensen’s poetry and is thus well acquainted with her oeuvre) says regarding these two books:

Her lifelong themes are already evident: boundaries between self and other, between human beings and the world; our longing and struggle for direct connection beyond boundaries; the roles of language and writing as mediators of that connection; the distances between words and the phenomena that they stand for.

Images drawn from nature, domestic settings, and corporeal existence feature throughout these poems, with a strong sense of the landscape, the seasons, and the musicality of her homeland. Many of the pieces in both volumes tend to be shorter and lighter in form, though the not necessarily in content, but notably, the final poem in Grass, the sequence “Meeting,” is longer , closer to prose poetry, and seems to presage sections that will later emerge in Det/It.

The unknown is the unknown and gold is gold I’ve heard, one

. winter the birds froze fast to the ice without the strength

. to scream, that’s how little we can do for words with words

the books press close to one another and hold themselves up,

. backs to the living room, our buttoned-up words huddle

. on the shelf, the queue-culture of centuries, inexorably

. built up word by word, for who doesn’t know that the

. word creates order

(from “Meeting: V” / Grass)

The third work collected in this volume, Letter in April, seems quite different in tone, quieter and more intimately focused. It arose as the result of a collaboration with graphic artist Johanne Foss who began with a series charcoal-on-parchment drawings based on Etruscan artworks. Christensen and Foss had known each other for a number of years and both had spent time at an artists’ residence in Italy and explored Etruscan ruins. Taken by Foss’s drawings, Christensen chose some and began writing responses to her images. These responses began as prose pieces, but she ended up discarding them and beginning again in poetry. Their project developed over two years as they worked together during the summer months while their children played. Several themes emerge in this work including parenthood, wonder, nature, and the account of a woman who travels to a foreign country with a child inspired by a trip Christensen took to France with her young son as part of her writing process.

Unpacking our belongings,

some jewelry

a few playthings

paper,

the necessities

arranged within

the world

for a while.

And while you draw,

mapping out

whole continents

between the bed

and the table,

the labyrinth turns,

hanging suspended,

and the thread

that never leads out

is, for a moment,

outside.

(Section I, º )

However, more than a series of poems and drawings, Letter in April follows a complex yet unassuming structure. Each of the seven sections contains five segments marked by a sequence of small circles in varying order. For example, Section I follows the pattern: º º º º º, º º º º, º, º º, º º º . Section II begins with º º º , and likewise each section begins with the same marking as the final segment of the one preceding. These markings link poetic segments with shared motifs, allowing the entire work to either be read straight through, or by following the each pattern individually (i.e. I º, II º, III º, IV º, and so on). This flexibility reflects Christensen’s musical and mathematical instincts, which are also apparent in the arrangement of elements of Det/It, but will be given full reign in her wonderful numerically and alphabetically framed poem Alphabet (1981).

Light, Grass, and Letter in April is a rich compilation of poetry that offers insight into Christensen’s development as a poet from the mid-twentieth century inspired modernism of her earliest work, through to a collaboration (unique in her oeuvre) that incorporates visual and dynamic elements. It is essential for those who already know and love her poetry, but can also serve as an introduction for those who have yet to encounter her masterworks.

So here we sit

in this violent solitude,

where bulbs work

underground,

and we wait.

Around noon

when the mountain rain stops,

a bird stands

on a stone.

Around evening

when the heart stands empty,

a woman stands

in the road.

(from IV º º º º º)

Light, Grass, and Letter in April by Inger Christensen, is translated from the Danish by Susanna Nied, with Drawings by Johanne Foss. It is published by New Directions.

I am very impressed by her work.

Odd, with all her riches available, I always go back the first that I read, Alfabet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a terrific book. Alfabet (and Det) are both books that appeal to audiences beyond those who normally read poetry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And the project continues! Do you think you might feel bereft if/when you conclude your project, or will you simply read in a circle?

I wonder, what distinguishes a poem that is 200 pages long from a novel written in verse. Or whether that’s even an answerable question.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is still one collection of poetry that I do not have and I think I will hold off on it for now just to have something to look forward to.

Her 200-page poem is actually a sequence of poems that are organized into an overarching structure. It does not tell a story, its more of a cosmic, metaphysical poem that I think really spoke to the late 60s mood and anti-war sentiment. It is perhaps more like a long musical piece/rock opera than a novel in verse.

LikeLike