In his Publisher’s Note to the French edition of Roland Barthes’ Incidents, a collection of essays published shortly after the theorist’s death in 1980, François Wahl suggests that the four very different texts assembled form a coherent whole because each piece “strives to grasp the immediate”. These are not theoretical or critical investigations in any sense, rather, in each text, Barthes is immersed in the moment, observing, reflecting, and recording his reactions. There is an unchecked flow and intimacy, by turns nostalgic, sensual, and melancholic but always tuned to the instance of occurrence: to the incident.

These are works that invite the reader to engage with all five senses, mediated through words and memory–they are not formal pieces but rather take the form of journal entries, diary writing, and fragmented travelogue. Barthes writes people and he writes place, never really entirely at ease with too much of either. Delight, boredom, and sadness filter through his reflections creating an immediacy that is at times startling. He is not writing for posterity, he is writing for himself.

These are works that invite the reader to engage with all five senses, mediated through words and memory–they are not formal pieces but rather take the form of journal entries, diary writing, and fragmented travelogue. Barthes writes people and he writes place, never really entirely at ease with too much of either. Delight, boredom, and sadness filter through his reflections creating an immediacy that is at times startling. He is not writing for posterity, he is writing for himself.

The collection opens with “The Light of the South West”, an evocative essay/memoir, a personal tribute to the south west region of France. He writes about the experience of traveling south from Paris. Passing Angoulème he becomes aware that he is on the “threshold” of the land of his childhood. It is the quality of light that defines the place:

. . . noble and subtle at the same time; it is never grey, never gloomy (even when the sun isn’t shining); it is light-space, defined less by the altered colours of things . . . than by the eminently inhabitable quality it gives to the earth. I can think of no other way to say it: it is a luminous light. You have to see this light (I almost want to say: you have to hear it, hear its musical quality). In autumn, the most glorious season in this land, the light is liquid, radiant, heartbreaking since it is the final beautiful light of the year, illuminating and distinguishing everything it touches. . .

He goes on to turn his attention to the elements of the south west that resonate with different aspects of his childhood, to reflect on the way that memories formed in childhood inform way we remember the places associated with that time, the magical spaces and the difficult times will each carry their own tone, their own qualities.

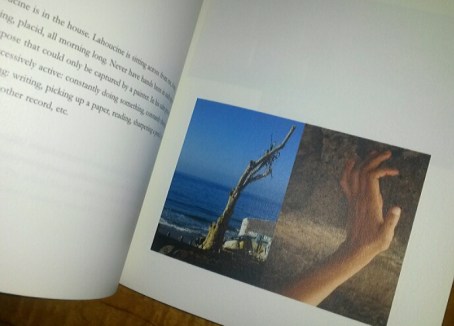

The title piece is the earliest in the book. Recorded in 1969 when the author was in his mid-50s, “Incidents”, as the name implies, captures moments from an extended stay in Morocco through an incidental series of fragmented encounters and experiences. Here, people form the scenery; with a special attention reserved for young men. Barthes demonstrates a a particular eye for detail (and somewhat of an obsession with hands) in these passing observations, combined with an acute sensitivity for scents and colours. The vibrancy, shades and contrasts of the country come alive. As a reader you become aware of the blinding light, the dark shadows–they are not described, you sense them in the background.

The title piece is the earliest in the book. Recorded in 1969 when the author was in his mid-50s, “Incidents”, as the name implies, captures moments from an extended stay in Morocco through an incidental series of fragmented encounters and experiences. Here, people form the scenery; with a special attention reserved for young men. Barthes demonstrates a a particular eye for detail (and somewhat of an obsession with hands) in these passing observations, combined with an acute sensitivity for scents and colours. The vibrancy, shades and contrasts of the country come alive. As a reader you become aware of the blinding light, the dark shadows–they are not described, you sense them in the background.

A young black man, wearing a crème de menthe-coloured shirt, almond green pants, orange socks and, obviously, very soft red shoes.

A handsome, mature looking young man, well dressed in a grey suit and a gold bracelt, with delicate clean hands, smoking red Olympic cigarettes, drinking tea, is speaking quite earnestly (some sort of civil servant? One of those who track down files?), and a tiny thread of saliva drips onto his knee. His companion points it out to him.

Some young Moroccans–with girlfriends they can show off in front of–pretending to speak English with exaggerated French accents (a way of hiding the fact without losing face that they will never have a good accent).

The art of living in Marrakesh: a fleeting conversation from open carriage to bicycle; a cigarette given, a meeting arranged, the bicycle turns the corner and slowly disappears.

The Marrakesh soul: wild roses in the mountains of mint.

The third essay, “At Le Palace Tonight . . .” is a tribute to a Paris club in a converted theatre. He describes the ornate detail, the mood and the atmosphere of this place where he seems to almost prefer to be an observer, watching the dancers and the human interactions rather than taking part. And as in the first essay, we find once again a wonderful evocation of light, this time light as informed by the interior of a structure:

Isn’t it the material of modern art today, of daily art, light? In ordinary theatres, the light originates at a distance, directed onto the stage. At Le Palace, the entire theatre is the stage; the light takes up all the space there, inside of which it is alive and plays like one of the actors: an intelligent laser, with a complicated and refined mind, like an exhibitor of abstract figurines, it produces enigmatic shapes, with abrupt changes: circles, rectangles, ellipses, lines, ropes, galaxies, twists.

This collection closes with “Evenings in Paris” a series of journal entries from 1979 that open with words Schopenhauer wrote on a piece of paper before he died: “Well, we’ve escaped very nicely.” The Barthes who comes through in this selection is tired, often impatient with colleagues and irritated by noise. A certain loneliness and dissatisfaction underscore his descriptions of dinners with friends, failed attempts to win the affections of the younger men he covets, and an unresolved mourning for his beloved mother. Most nights he finds himself heading home alone, half despairing, half relieved, to settle into bed in the company of Pascal, Chateaubriand, Dante, or the echoing ghost of Proust. Although he still enjoys longingly watching attractive men, he has little patience for crowds or social functions. This is a heavier, more emotionally intense offering, the intimacy of “the immediate” weighs heavily as Barthes commits his thoughts to paper, unaware in the writing as we are in the reading, that he is nearing the end of his life.

And, because he is recording the ordinariness of the daily encounter of the self with the world, there is the possibility of shock waves that ring down the years with a new intensity in light of the incidents (that word again) that have unsettled Paris in recent years:

And, because he is recording the ordinariness of the daily encounter of the self with the world, there is the possibility of shock waves that ring down the years with a new intensity in light of the incidents (that word again) that have unsettled Paris in recent years:

The guy who sells Charlie-Hebdo walks by; on the cover in the publication’s idiotic style, there’s a basket of greenish heads that look like lettuces: ‘2 francs the head of a Cambodian’; and, right then, a young Cambodian rushes into the café, sees the cover, is visibly shocked, concerned, and buys a copy: the head of a Cambodian!

Not without a little social commentary, even in a deeply personal journal, Roland Barthes, remains ever relevant down the years.

Reading Incidents is, in itself, a sensuous experience, it is doubly so in this edition from Seagull Books. With a sparkling fresh translation by Teresa Lavender Fagan and illustrated with the evocative photographic images of Bishan Samaddar, this collection of writings becomes one that can, as Barthes himself would have intended, be savoured.