i looked into his low eyes

black, tired

i looked into his heart

and that splotch of vigor

made me

ephemeral, tardy, rancid, and fleetingwe arrive at the altar

in a state of absorption

i request a living offering

start to cough, phlegmy

till i’ve nearly smashed to pieces

at his feet– from “opium weddings”

The poetry of Julia Wong Kcomt turns on the unexpected, crosses cultures, languages and borders, reflecting who she is, where she comes from and where she has travelled to and lived. Born into a Chinese-Peruvian (tusán) family in the desert city of Chépen, Peru, in 1965, she was a prolific writer whose work included eighteen books of poetry, along with a number books of fiction and hybrid prose. Questions of identity and belonging are central to her writing, as are themes of migration, motherhood, and the body.

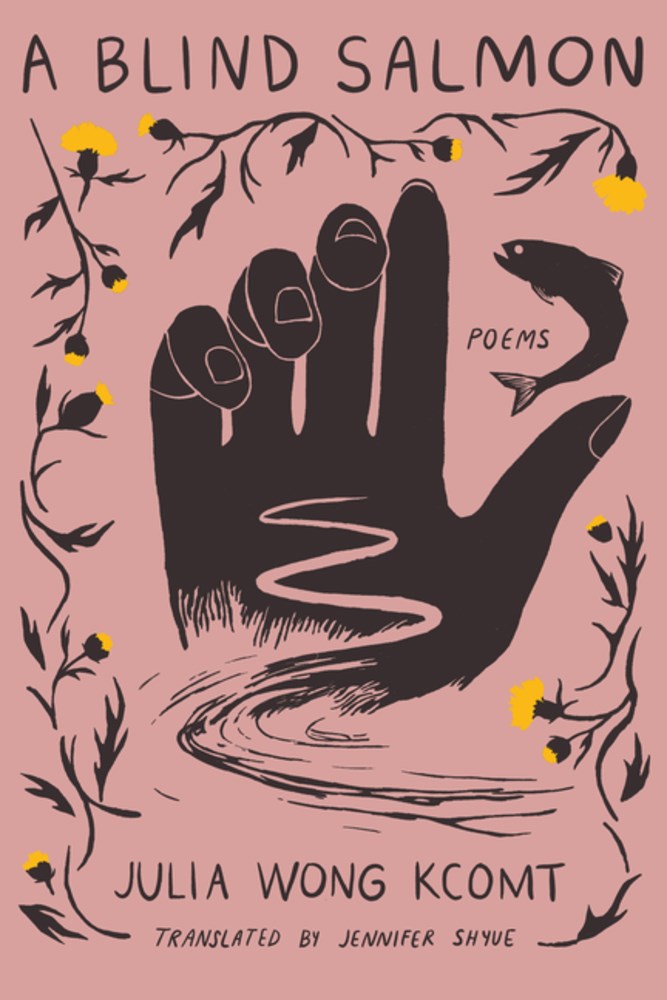

A Blind Salmon, her sixth collection, originally published in 2008, is her first full-length work to be published in English translation. Translator Jennifer Shyue who has a particular interest in Asian-Peruvian writers, has been engaged with her and her poetry for several years making this volume a welcome introduction to an intriguing and important poetic voice. Sadly, however, Kcomt did not live to see its release; she died in March of this year at the age of 59.

A Blind Salmon, her sixth collection, originally published in 2008, is her first full-length work to be published in English translation. Translator Jennifer Shyue who has a particular interest in Asian-Peruvian writers, has been engaged with her and her poetry for several years making this volume a welcome introduction to an intriguing and important poetic voice. Sadly, however, Kcomt did not live to see its release; she died in March of this year at the age of 59.

Composed while she was living in Buenos Aries, the poems in this dual-language collection, often involve a shift between languages—Kcomt was multilingual, speaking Spanish, English, German, and Portuguese—creating a challenge of sorts for Shyue, especially when the original contains English. This is handled with the use of an alternate sans serif typeface when appropriate, or by bringing Spanish into her English translation for the words or lines in English in the original, as in the poem “tijuana big margarita.” When German arises, it is left as is. This shifting linguistic terrain, like the sands of the region she comes from, adds texture and variation when they appear.

The poem “on sameness” which is repeated or echoed in the collection, is another wonderful example of the multilingual dynamic at play. The first appearance features Kcomt’s own English version of her poem “sobre la igualdad,” presented in two different typefaces on facing pages (the regular typeface and that which is used to denote English in the original). The wording is, naturally, identical. It opens:

in the circle, sweet circle

of intense immortalitywhere is my china?

the land with no owners

the face is not repeating itself

Later, when the poem is revisited, Kcomt’s Spanish original faces Shyue’s translation, which she made before reading the poet’s own translation (or at least refreshing her memory of a more distant encounter). The similarities and differences shine a light on the perspective a translator brings to her reading of another’s work—line by line and as a whole:

in the circle, sweet circle

of intense immortalitywhere my faraway chinese country stayed

the great country of all

where no faces repeat

This collection contains a mix of verse and narrative prose poems, the latter sometimes stretching on for three or more pages and offering a broader canvas for the exploration of identity and belonging, in some instances twice removed when set in Germany where Kcomt studied for a time. They address trying to find a home of some sort, balancing relationships, and finding invisible lines can be crossed in an instant as in “aunt emma doesn’t want to die” where the Asian-Latin American speaker, a foreign student, offends her elderly employer with her attraction to a man in a photo (“no looking, margarita. he’s not for you.”) and is forced to leave her home:

when i was moving out, you wouldn’t look at me. at the geographic latitudes i’m from, we’re unfamiliar with that feeling, is it called ethnic guilt? perpetuation of folklore.

reiner was the forbidden fruit next to that tiger from kenya and you hated me because I took a bite that full-moon night as the children danced in costumes in the square.

[. . .]

and though i thought reiner would come looking for me or call me, that didn’t happen. not that it would have been necessary. his torso had imprinted on my groin. sometimes skin serves as a sort of reproduction.

in student housing i was once again surrounded by people like me. foreigners. it’s so hard to be stranger, to come from elsewhere, to fight, to steal, to do anything to get inside and the insiders throw you bait only to take it away.

The poems in A Blind Salmon seem to become increasingly charged with life and energy each time they are revisited. Kcomt’s speakers are bold and unapologetic, reaching out with language that is sensual, unexpected, unsettling. Her images are often startlingly corporeal, yet always touching the tender complexities of being in the world, a world that does not always no how to understand you, or you it, but one that is fully alive.

A Blind Salmon by Julia Wong Kcomt is translated from the Spanish by Jennifer Shyue and published by Deep Vellum/Phoneme Media.