Humans have become alienated from their own history, as they are from their own cosmic nature.

– “Mass and Spirit”

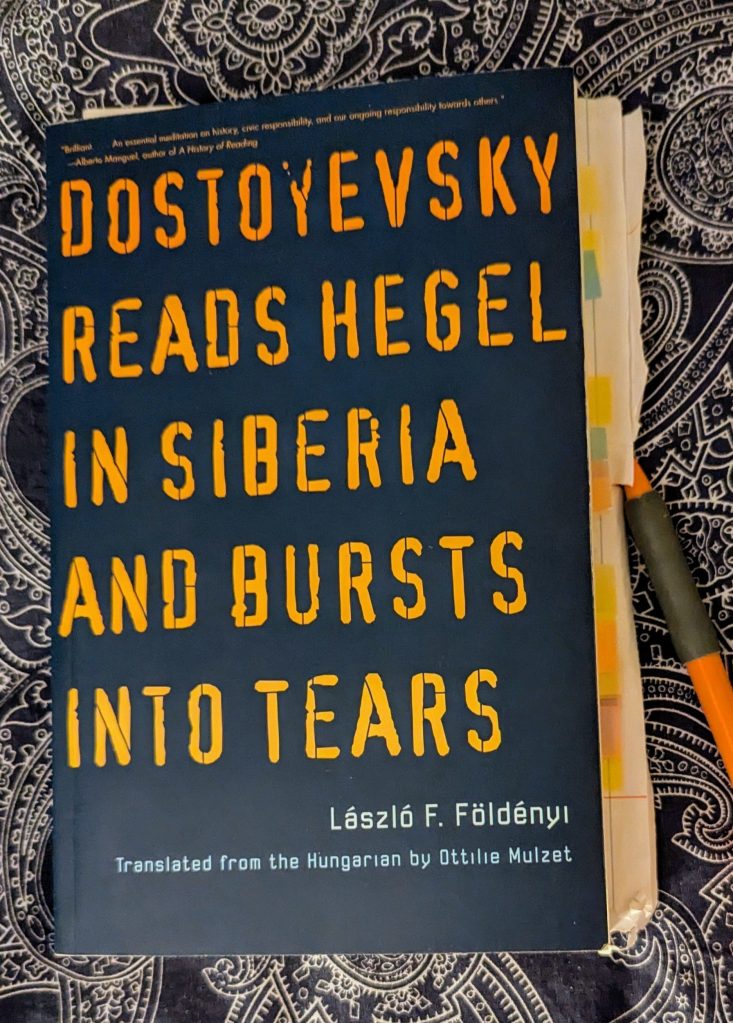

The title is irresistible. It is impossible to read it and not wonder: what is this book about? In truth, it is about many things, or rather, many ideas, but in essence they can all be understood as variations on a dichotomous theme: darkness and light. Pivotal to these inquiries is the lasting impact of post-Enlightenment thinking on a traditional understanding of metaphysics, that is, questions of being and the nature of reality. Where once religion, or belief in God, gods, or some transcendent quality of existence could be turned to in times of darkness, the Enlightenment heralded a belief in “the omnipotence of reason that illuminates all phenomena.” Yet, as László Földenyi posits in this wide-ranging collection of essays, adroitly translated by Ottilie Muzlet, darkness and light (or other similar opposites or variants) are inextricably linked—one cannot be imagined or understood without the other—but in our secularized modern age, we, in our restricted, nondivine omnipotence can find ourselves confronting our own fragility in situations where reason alone may not seem like enough to fall back on. What then?

In his explorations of this conundrum, Földenyi, a Hungarian critic, essayist and professor of art based in Budapest, entertains the ideas, experiences and tribulations of a broad cast of thinkers, writers, poets, artists, and literary figures including Elias Canetti, Heinrich von Kleist, Caspar David Friedrich, Nietzsche, Novalis, Marquis de Sade, Antonin Artaud, and many more. And, of course, the protagonists of the evocatively titled eponymous essay: Dostoyevsky and Hegel. As he examines the manner in which rationalism, and within it a constrained idea of freedom and existence, has been met by those who chafed against its confines to a greater or lesser extent, Hegel is often assigned to the role of advocate for the primacy of logic and reason—not necessarily always fairly—so he makes a regular appearance in a number of pieces. But his main starring role is as philosophical foil to a certain Russian writer exiled to Siberia.

In his explorations of this conundrum, Földenyi, a Hungarian critic, essayist and professor of art based in Budapest, entertains the ideas, experiences and tribulations of a broad cast of thinkers, writers, poets, artists, and literary figures including Elias Canetti, Heinrich von Kleist, Caspar David Friedrich, Nietzsche, Novalis, Marquis de Sade, Antonin Artaud, and many more. And, of course, the protagonists of the evocatively titled eponymous essay: Dostoyevsky and Hegel. As he examines the manner in which rationalism, and within it a constrained idea of freedom and existence, has been met by those who chafed against its confines to a greater or lesser extent, Hegel is often assigned to the role of advocate for the primacy of logic and reason—not necessarily always fairly—so he makes a regular appearance in a number of pieces. But his main starring role is as philosophical foil to a certain Russian writer exiled to Siberia.

“Dostoyevsky Reads Hegel in Siberia and Bursts in Tears” is a vivid exercise in imagination which takes us to Semipalatinsk in southern Siberia where Dostoyevsky was sent in 1854, to serve a period of military service following four years of forced labour. In this barren, desert environment, he lived in a sparely furnished room and made friends with the young local prosecutor, Aleksander Yegorovich Vrangel, with whom he recited poetry, discussed religion, most critically, studied the books that Vrangel was able to secure for him. There is some reason to believe that one of the authors they read together was Hegel, possibly his lectures on the philosophy of world history, either ordered from Germany or in the form of the book in which they had been gathered and published. Földényi enthusiastically admits that he is taking liberties with his assumptions, but the notion is too tempting to resist.

Dostoyevsky emerged from his years of imprisonment and exile, as a man and writer whose experience with hardship and isolation had ignited a metaphysical drive that he would go on to channel against nineteenth century Europe’s adherence to utilitarianism and rationality through his protagonists. For Hegel, history, despite its messiness and violence, could only be properly understood as the logical, progressive march of reason. That which fails to conform—at least in terms a European mind might understand, as such Africa and Siberia—is relegated to stand outside of the historical process and to be worth no further consideration.

If the infinite and the transcendent become lost behind the finite things, then it is no longer possible to speak of freedom. God, subjugated to rationality, is not the God of freedom, but of politics, conquest, and colonization. This is the secular religion of the God of the modern age. And history—looking at it from a Hegelian point of view—is the history of secularization. Dostoyevsky might have justifiably felt that Hegel was not just ushering Siberia (and himself with it) out the door; he was trying to convince, in missionary-like fashion, all humanity to accept as historical only that which the censorship of rationality admitted as such.

In envisioning an intellectual clash between the ideals represented by Hegel, and Dostoyevsky’s own experience of life in a place deemed separate from history, under conditions he would never have known had he not been forced to leave Europe, Földényi sees the ground for the openly acknowledged spiritual transformation that the Russian underwent in Siberia, and the writer he would become.

This may be the most passionate essay in the collection, but many of the smaller, quieter pieces turn on equally intriguing ideas in an open, speculative manner. He writes, for example, about happiness and melancholy, fear and freedom, sleep and dreams. Often his intention is to push beyond a simple dichotomy, at other times he wishes to dig down into an idea through the examination of the lives and ideas of one or more individual who found themselves confronting the limitations imposed by a society dedicated to the furthering of rational ideals. Case in point, in the also cleverly titled “Kleist Dies and Dies and Dies,” Földényi unwinds Kleist’s trajectory from an enthusiastic supporter of Enlightenment ideas through an early “Kantian crisis” which shattered his faith that Truth was knowable, to an act—possibly inspired in part by Goethe’s Werther—that eclipsed any of his writing: his carefully orchestrated double suicide with Henriette Vogel on November 21, 1811.

It bears repeating: the death of Kleist is the most thoroughly documented event of his entire life. The French-Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran justifiably states that it is impossible to read even one line of Kleist without thinking of how he put an end to his own life. His suicide preceded, as it were, his life’s work.

It is tempting to consider, and Földényi obliges, how Kleist’s embrace of death, or the act of dying, might be an answer to the loss he felt in an uncertain world.

The pieces in this collection were published in their original form (some have been substantially revised) between 1990 and 2015. They are not presented chronologically, nor can they be read as one cohesive argument, not least due to the fact that times, and presumably their author’s views, change. But it is telling that the volume opens and closes with essays addressed to Elias Canetti: the first, “Mass and Spirit” written in honour of his ninetieth birth anniversary, the latter, “A Capacity for Amazement,” an examination of his seminal Crowds and Power, fifty years after its original publication in 1960. His examination of Canetti’s exploration of the universal crowd and its ambiguous role in human history is measured, at least for Földényi, against Hegel’s understanding of universal freedom as a rational ideal. For Canetti, the crowd is more than a gathering of humans, it transcends that simple notion to incorporate all natural phenomena, it is cosmic and inherently irrational. Although he may or may not be onside with all the implications of Canetti’s singular arguments, Földényi clearly admires his metaphysical energy and, as the title suggests, his capacity for amazement.

The best essays wrestle with ideas, challenge assumptions, and invite the reader to entertain possibilities, debate with them or, even better, be inspired to read further. Dostoyevsky Reads Hegel is filled with references to so many writers and works that it is impossible not to stop to look someone or something up, or pull a volume off one’s shelves. It encourages side trips down rabbit holes. And that is what is so rewarding about spending time with László Földényi and the fascinating company he keeps.

Dostoyevsky Reads Hegel in Siberia and Bursts into Tears by László Földényi is translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet and published by Yale University Press.