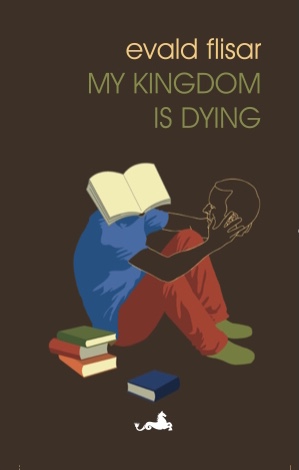

Evald Flisar (b. 1945) is one of Slovenia’s best known and most prolific writers. He has travelled extensively, his work has been translated into at least forty languages, and his plays have been performed around the world. But, as is not uncommon for writers from his corner of Europe, it is one thing to be widely read, quite another to be a household name—at least beyond one’s native borders. This is, in fact, something that is a fate long understood by the aging narrator of My Kingdom is Dying, subtitled Storytelling at the End of the World, a characteristically unusual tribute to the life of a writer, originally published in Slovene in 2020, and now available in David Limon’s English translation, just in time to honour the author’s eightieth birthday earlier this year.

This charming and slyly subversive novel is a celebration of the power of storytelling, formally and informally. The unnamed protagonist is a highly respected novelist and short story writer who, like Flisar himself, has travelled widely and lived and worked in both Slovenia and London. He is quite a quirky, at times even arrogant, character whose life story, as he tells it, has all the qualities of a sophisticated tall tale, one that is gleefully anachronistic, blending profound insights with absurd happenings, and blurring the line between possible fact and pure fantasy. The basic narrative unfolds as the narrator is recovering from a freak accident with the daily assistance of a live-in Carer with whom he shares accounts of his past, including his early development as a writer with the encouragement of his grandfather, the pleasures and pitfalls of his career, his life-long obsession to write a completely original story, and the mysterious figure of Scheherazade who, as if emerging from his youthful reimagining of the Arabian Nights, has followed him around the world, appearing when he least expects it.

This charming and slyly subversive novel is a celebration of the power of storytelling, formally and informally. The unnamed protagonist is a highly respected novelist and short story writer who, like Flisar himself, has travelled widely and lived and worked in both Slovenia and London. He is quite a quirky, at times even arrogant, character whose life story, as he tells it, has all the qualities of a sophisticated tall tale, one that is gleefully anachronistic, blending profound insights with absurd happenings, and blurring the line between possible fact and pure fantasy. The basic narrative unfolds as the narrator is recovering from a freak accident with the daily assistance of a live-in Carer with whom he shares accounts of his past, including his early development as a writer with the encouragement of his grandfather, the pleasures and pitfalls of his career, his life-long obsession to write a completely original story, and the mysterious figure of Scheherazade who, as if emerging from his youthful reimagining of the Arabian Nights, has followed him around the world, appearing when he least expects it.

His adventures are extraordinary and feature an diverse range of real life authors and literary figures—at times holding close to actual details, like the arc of a Borges story or the make-up of a real Booker Prize jury—but because it also leans toward the bizarre, Flisar is able to get away some pretty pointed observations about the literary world with all its pretensions. His narrator takes swipes at critics, fellow writers, editors, publishers, and prize juries. But one must assume that much of this is levelled with tongue firmly planted in cheek. After all, one of our hero’s regular targets is genre writers—in contrast to serious writers of literature such as himself—all in what is a clear genre hybrid blending memoir (fictitious and factual) with fairytale, horror, mystery, and fragments of travelogue. (Of note, several accounts take place in India, and, for the absurdity of events that unfold there, Flisar’s familiarity with the country and its cities, especially Kolkata, is evident.)

By the narrator’s own account, everything was proceeding smoothly, book deal followed book deal, until the sudden onset of writer’s block upended his world. One day, stories presented themselves to him as usual, rising out of a daily act so pedestrian as opening the newspaper over his morning coffee and the next day, the well had inexplicably run dry. No stories came. If storytelling gave him his meaning, not to mention a career, what might be the fate of a storyteller who could no longer tell stories?

It had never seemed possible that it would be storytelling that would bring me to the edge of a nervous breakdown and change me into the kind of person who I liked to write about. This time it happened, not within the framework of an imagined story, but in the reality in which I was forced to live, even if only because of loyalty to the activity that I saw as my “mission”, for I knew that withdrawal from the world, when we lack a way forward and begin to psychologically drown, is always possible and, with the abundance of chemical means available, can also be painless, even instant. But each such thought, that I might withdraw from the world before my natural end (thus showing that I was not a victim, but rather the master of my fate), automatically became transformed into a story that I simply had to write and share with others. With that, the wish for a leap into the next life lost its power and validity.

Now without this critical lifeline, would he be able to hold off his darkest thoughts? When he confessed his predicament to his editor, it was suggested that he seek treatment, all expenses paid, at an exclusive clinic in Switzerland where his writer’s block might be cured. The clinic, ominously named Berghof, turns out to be a dark, dank castle in the middle of a lake where, so far as he can tell, all of his fellow patients seem to be seriously mentally ill. The treatment is absurdly brutal, the doctors appear to be madmen, and it is not until he emerges from his solitary routine that he finds himself among the likes of Saul Bellow, Martin Amis, J.M. Coetzee, Graham Greene, and others. And it just gets stranger from there.

Flisar has a fondness for exploring serious themes within environments that are by turns whimsical and grotesque (see my review of My Father’s Dreams). He is especially interested in the behaviour his characters exhibit under psychological pressures—and his protagonist here is subject to more than a few impulsive reactions when he feels threatened. But, at the same time, in narrating his story to his Carer, a woman he grows increasingly close to, he is able to maintain the storyteller’s objective distance, at least until boundaries between myth and reality finally dissolve. In the end, despite—or perhaps because of—its many spirited and unlikely detours, My Kingdom is Dying is a tribute to storytelling so rich with literary illusions and intertextual elements that it holds a depth its seemingly light, eccentric tone belies.

My Kingdom is Dying by Evald Flisar is translated from the Slovene by David Limon and published by Istros Books.