The unique challenge that arises when one attempts to write about what it feels like when the experience of gender fails to conform with cultural and societal expectations is rooted in the problem of a lack of consensus about terminology. Whether language and meaning are defined by individuals with lived experience or those looking in from the outside, there is no one way to talk about gender identity. There are the absolutists who see male and female / woman and man as fixed black and white entities among both those who identify as transgender and those who deny our existence. And then there are those accept and relate to the notion of a spectrum or continuum in lived expression (reflecting but not necessarily mirroring the intricacies of genetic variation). But transpeople are, first and foremost, people, and our understanding of ourselves not only evolves and changes over time, it is typically measured against those we encounter in the world. And often that can involve many years of wondering where to find our own selves reflected. Just like other people who, for some reason or another, feel a persistent sense that they do not belong.

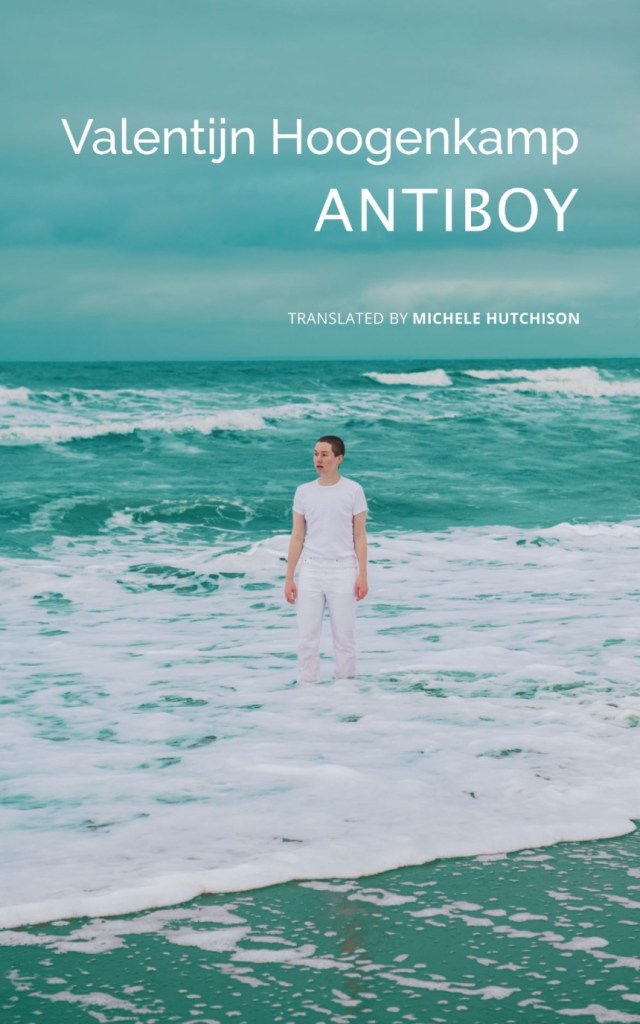

Antiboy, by Dutch poet and writer Valentijn Hoogenkamp, is an attempt to articulate the strangeness, the sorrow, and the satisfaction that can accompany the quest for a more natural way of being. This very spare memoir, translated in crisp, poetic prose by Michele Hutchison, chronicles the author’s lifelong inability to find himself within the female body and life into which he was born. When a genetic mutation for a rare form of cancer (one that will claim his mother’s life) necessitates that he undergo a bilateral mastectomy, he finds an unexpected opportunity to explore his identity. Much to the consternation of others, he rejects breast implants and opts for a flat chest:

Antiboy, by Dutch poet and writer Valentijn Hoogenkamp, is an attempt to articulate the strangeness, the sorrow, and the satisfaction that can accompany the quest for a more natural way of being. This very spare memoir, translated in crisp, poetic prose by Michele Hutchison, chronicles the author’s lifelong inability to find himself within the female body and life into which he was born. When a genetic mutation for a rare form of cancer (one that will claim his mother’s life) necessitates that he undergo a bilateral mastectomy, he finds an unexpected opportunity to explore his identity. Much to the consternation of others, he rejects breast implants and opts for a flat chest:

‘When I got the diagnosis, I pictured my funeral and that nobody there would really know me because I’ve never spoken up. And, in the conversations I had at the hospital, they kept telling me what most women would do in my situation,’ I say. ‘I kept wanting to look over my shoulder and see if that woman was standing behind me.’

‘Because you don’t feel like a woman?’

‘I thought femininity was something that could be learned.’

This is a searching text. Unsentimental and questioning, not stubborn and defensive like some other memoirs that venture into this territory. Hoogenkamp speaks not so much of a boy inside, but an absence where a girl or woman should be. An emptiness. The surgery presents the means to open himself to physical transformation—breasts being such fundamental indication of womanhood—but his decision to forgo implants is not random, there is precedent reaching back much further. He describes the childhood of a social outcast. Set aside. “No one to walk hand in hand to the gym with, to go around to the classes with on my birthday.” Girls playing together in the schoolyard seem strangely alien.

I can do this. I have the same arms and legs as them, I am approximately the same size. I can be one of them.

It should be easy. Natural. But it is not.

Sexuality is another avenue for exploration. Sexuality and gender can easily be conflated, both can be subject to labelling by others or rejection of an individual’s right to define themselves. Hoogenkamp has boyfriends and a female friend she has sex with—a female friend who will, in time, transition to male and provide a little guidance along the way. But his intimate partners prove less flexible than he would hope once he comes out as non-binary. And he allows himself to be used:

My sexual orientation was being wanted. I was sick to death of feeling unwanted.

Although Hoogenkamp finds a space to exist between genders (but adopting male pronouns), there is so much in this short book that resonated deeply with my own experiences growing up without any context for my sense of otherness, my attempts to understand myself through questions of sexuality, and my ultimate decision to transition more than twenty years ago. There are many ways of feeling and talking about a gender anxiety or disconnect, just as there are many ways of trying to describe how one knows that their sex and gender are aligned. At one point Hoogenkamp puts that question to a number of non-trans-identified men and women and finds many hard pressed to articulate an answer. But at a time when differences in gender identity are increasingly being denied or weaponized, it is more important than ever to listen to the varied personal experiences of transgender people.

Antiboy by Valentijn Hoogenkamp is translated from the Dutch by Michele Hutchison and published by Seagull Books as part of their Pride List.