For months The Jew Car, Franz Fühmann’s autobiographical story cycle, sat on my shelf unread. I had bought it in anticipation of the recent release, in translation, of his last major work, At the Burning Abyss: Experiencing the Georg Trakl Poem. However, for some reason, I could not bring myself to read it. I have never been especially attracted to World War II literature, and with the current resurgence of neo-Nazi sentiments and far-right movements in North America and Europe, I was uncertain if I wanted to venture into a series of stories in which an East German writer traces a path from his enthusiastic adoption of fascist rhetoric as a youth, on through his experiences as a German soldier during the war, to his eventual rejection of Nazi ideology and acceptance of socialism in a Soviet POW camp. I wondered if I had the heart for it, and yet the translator of both volumes, Isabel Fargo Cole, advised me that Fühmann’s personal reflections in At the Burning Abyss would have greater impact and resonance with the background afforded by The Jew Car.

Born in 1922, Fühmann grew up in the predominantly German Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia, the son of an apothecary who encouraged the development of a strong German nationalism. From the age of ten to fourteen, he attended a Jesuit boarding school in Kalksburg but found the atmosphere stifling. In 1936, he transferred to a school in Reichenberg, where he lived on his own for the first time and became involved in the Sudeten Fascist movement. After the annexation of Sudetenland in 1938, he joined the SA. 1941, he was assigned to the signal corps serving in various locations in the Ukraine before being moved to Greece as Germany’s fortunes declined. He was captured by Soviet forces in 1945. During his years spent as a POW, he would embrace socialism and upon his release in 1949, he finally found himself on German soil for the first time, settling in the GDR where he would spend the rest of his life.

Born in 1922, Fühmann grew up in the predominantly German Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia, the son of an apothecary who encouraged the development of a strong German nationalism. From the age of ten to fourteen, he attended a Jesuit boarding school in Kalksburg but found the atmosphere stifling. In 1936, he transferred to a school in Reichenberg, where he lived on his own for the first time and became involved in the Sudeten Fascist movement. After the annexation of Sudetenland in 1938, he joined the SA. 1941, he was assigned to the signal corps serving in various locations in the Ukraine before being moved to Greece as Germany’s fortunes declined. He was captured by Soviet forces in 1945. During his years spent as a POW, he would embrace socialism and upon his release in 1949, he finally found himself on German soil for the first time, settling in the GDR where he would spend the rest of his life.

Originally published in 1962, the stories in The Jew Car, which is subtitled Fourteen Days from Two Decades, follow the trajectory of Fühmann’s life between the ages of seven and twenty-seven. Presented with dramatic colour, they offer an attempt to explore the progression of his ideological development during this period. Through an engaging, often ironic voice and well-framed narratives, we watch Fühmann’s fictional alter-ego confront the psychological seduction of the persistent propaganda machine and engage in the mental gymnastics required to continually readjust to accommodate or explain away any evidence that failed to fit with what he has been led to believe.

The title story opens the collection. Set in 1929, the seven year-old narrator is caught up in a wave of rumours sweeping through his grade school. The children listen with a mixture of rapture and fear, to breathless tales of a four Jews in a yellow car who are said to have been travelling through the surrounding countryside, snatching and murdering innocent young girls. When our hero happens to spy a brown car carrying three people one afternoon, it becomes, in his imagination, vividly transformed into the feared mysterious vehicle exactly as described. At school the next day, he is the centre of attention, holding his classmates in thrall until the one person he dearly wishes to impress the most, the girl “with the short, fair hair” neatly puts him in his place. Yet rather than causing him to question his hasty assumptions about the car he actually saw, his humiliation is turned into an increased, abstracted hatred of Jews.

And so the process begins.

Fühmann manages to capture the mixture of naïve enthusiasm, patriotic fervour, and boredom that he and his friends regularly encounter as the tides of history are building around them. He is young, the air is charged with excitement mingled with fear of the dreaded Commune and the anticipation of liberation. At times his young narrator is surprised to catch the worried looks on the faces of his parents and other adults. His faith in the Führer is unshakable and he believes that the German Reich will not abandon the Sudeten German population to murderous cutthroats. This conviction is well captured in the story “The Defense of the Reichenberg Gymnasium.” (September, 1938) Although no violence has yet occurred in his corner of the region at this point, when an alarm summons him and his comrades from the Gymnastic Society to defend the Reichenberg gymnasium from imminent attack, he is ready and eager:

I was excited: I’d never been in a battle like this; the occasional school scuffles didn’t count, the scouting games and the stupid provocations of the police in which I and all the others indulged; now it would turn serious, a real battle with real weapons, and I felt my heart beating, and wondered suddenly how it feels when a knife slips between the ribs. My steps faltered; I didn’t think about the knife, I saw it, and as I passed Ferdl, a sausage vendor who stood not far from the gymnasium, I even thought of stealing off down an alley, but then I scolded myself and walked quickly into the building.

But, as uneventful hours begin to stretch well past lunch time, boredom and hunger start to set in. Ultimately it is decided to send forth a series of provisioning parties to remedy the situation. Young Fühmann is assigned to the third group:

It was a puerile game we were playing, childish antics, and yet murderous, and the awful thing was that we felt neither the puerility no the murderousness. We were in action, under orders, advancing through enemy territory, and so, the five-man shopping commando in the middle and the three-man protective flanks to the left and right, we casually strolled up the street, turned off without incident, made our way back down the parallel street through the tide of workers, Germans and Czechs coming from the morning shift, cut through the arcade, side by side, and at discreet intervals each bought twenty pairs of sausages with rolls and beer.

Fühmann is a gifted storyteller whose poetic prose and ironic tone are pitch perfect, especially in the earlier stories. He creates a portrait of his younger self that is not sentimental or idealized. His moments of empathy for individuals otherwise thought to be inferior are quickly reframed with racist convictions. He does not speak too much about his involvement in direct anti-Semitic actions (though he will in later works). What comes through most strikingly in The Jew Car is the sense of rational isolation that surrounds the individual. Information is strictly mediated, so that otherwise intelligent individuals lose any frame of reference or develop extreme responses to the continual routine of work and deprivation. His steadfast devotion to the military structure will start to weaken as he discovers poetry, although his first published efforts during the war are very much on message. Fühmann will not become a dissident poet until much later, long after the war is over.

The tone of the later stories is soberer, more contained. The narrator describes his conversion to Socialism in terms that border on the religious. He talks about having “scales fall from his eyes” during his training, describes reading Marx, encountered before but now understood in a new light. But he never provides detailed justification—he believes with conviction and is not ready to be swayed. The final tale which describes his arrival in East Germany after his release from imprisonment to join his mother and sister who have been relocated there, is forced and marked by Soviet style melodrama.

In his afterword to the 1979 reissue of The Jew Car, which aimed to address some of the editorial changes made to the original publication, Fühmann noted a shift in tone that impacted the overall flow of the collection:

Probably even while writing I began to sense the inconsistency in this work, expression of a fractured mindset, a switch from self-irony to affirmative pathos that had to lead to a decline in literary quality such as that between the first and last story…

However, although they are autobiographical in nature, these stories are essentially fictionalized—this is not an essay or memoir. That lends the collection a particular power and energy. Yet, there is a clear sense that the ending is idealized and incomplete, as indeed it is. As Isabel Cole’s Afterword goes on to explain, Fühmann’s infatuation with the socialist vision of the GDR will fade as he chafes against the rigid restrictions imposed on individual and creative expression. He will, nonetheless, remain in East Germany for the rest of his life. In 1982, two years before his death, he will publish an in-depth exploration of his personal evolution through his discovery of and affection for the poetry of Georg Trakl. To that work, At the Burning Abyss, my attention can now turn…

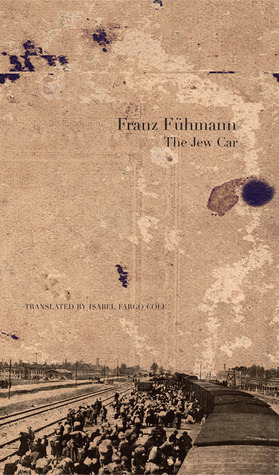

The Jew Car by Franz Fühmann is translated by Isabel Fargo Cole and published by Seagull Books.

This review, together with my review of Malina by Ingeborg Bachmann represents my contribution to this year’s German Literature Month. Also related: See my recent interview with translator Isabel Cole, primarily regarding Wolfgang Hilbig, but also touching on Fühmann, which was published at 3:AM Magazine this past month.

I understand entirely your feelings about engaging currently with anything covering the WW2/Nazi period. I read much of this kind of literature in the past but I doubt I could deal with it in that much depth nowadays. Nevertheless, this sounds powerful and nuanced, and we do need to keep trying to understand what happened in the past to aim to stop it repeating itself…

LikeLiked by 1 person

This book does afford a very interesting perspective, the ordinary soldier was very shielded and caught up in a vision. Fuhmann will go on to seriously confront the legacy of WWII as will many German writers of his generation and the following one. What is perhaps even more frightening when it comes to racist/fascist ideology is that very ordinary, otherwise intelligent people can get caught up—in the right circumstances it could be any one of us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds like it explores both the ideologies at the heart of twentieth century Europe: important if uncomfortable reading. Interestingly, it’s not that unusual for people to move from one extreme to another, though usually from left to right (though not in Max Aub’s Filed of Honour). I can see why you might be reluctant to read it – sometimes German Literature Month can throw up an excessive number of Nazis (in fiction I mean).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Although Fuhmann addresses the enormity of the crimes the Nazis perpetrated later in his life, what comes through in this work is how easy it is for young people to be swept up in the excitement of nationalism, and how, as a soldier who was primarily assigned to sending telegrams or roadwork crews—ordinary, unexotic tasks. The officers belonged to a different world and a telling encounter with an officer who had first encouraged his poetry writing upon his arrival in Germany in ’49 demonstrates the lingering impact of those differences.

LikeLike