I arrived in Olevano in January, two months and a day after M.’s funeral. The journey was long and led through dingy winter landscapes, which clung indecisively to grey vestiges of snow. In the Bohemian Forest, freshly fallen, wet snow dripped from the trees, clouding the view through the Stifteresque underbrush to the young Vltava River, which not had even a thin border of jagged ice.

As the landscape past the cliffs stretched into the Friulian plains, I breathed a sigh of relief. I had forgotten what it is like to encounter the light that lies behind the Alps and understood, suddenly, the distant euphoria my father experienced every time we descended the Alps.

The unnamed narrator of Grove arrives in Italy, fresh from the loss of her long-time partner, planning to spend three months contemplating the possibility of forcing her life “into a new order that would let me survive the unexpected unknown.” As she travels down from Germany, she stops in Ferrara, a town she had and M. had planned to visit on the Italian trip they would never manage to take together. But the literary landscape of Georgio Bassani will have to wait, at this time her destination is further south, a small village south-east of Rome. There she will walk the streets and roadways of the rolling landscape, orienting herself in relation to the house where she rents an apartment, the nearby cemetery and grove of trees. An anchor for an unanchored time.

German author and translator Esther Kinsky’s books cannot be rushed. They unfold slowly and linger in the imagination. Like her acclaimed novel, River, this meditation on grief offers an intimation of autofiction but I prefer to see her work as fiction bound to real-life experience and location that conceals as much as it reveals. Intimate yet not overtly confessional in nature. The focus is on immediate response to encounters, observations and memories, while autobiographical details tend to be limited, leaving both the author and her protagonist in the shadows. The narrator has recently lost her husband after a serious illness; Kinsky’s husband, Scottish-born German translator Martin Chalmers, died in October, 2014. The grief, the loss, is palpable, yet still too recent to be fully articulated, not only in the first section chronicling those early months alone, but in the third part set exactly one year later. M.’s memory haunts the narrator’s dreams, her attachment to an article of his clothing, his image. However, we learn very little of anything about him or their life together. Likewise, what the narrator is looking for and what she finds is unclear—as in River, it is the journey, or rather journeys, not the destination that guides the narrative.

German author and translator Esther Kinsky’s books cannot be rushed. They unfold slowly and linger in the imagination. Like her acclaimed novel, River, this meditation on grief offers an intimation of autofiction but I prefer to see her work as fiction bound to real-life experience and location that conceals as much as it reveals. Intimate yet not overtly confessional in nature. The focus is on immediate response to encounters, observations and memories, while autobiographical details tend to be limited, leaving both the author and her protagonist in the shadows. The narrator has recently lost her husband after a serious illness; Kinsky’s husband, Scottish-born German translator Martin Chalmers, died in October, 2014. The grief, the loss, is palpable, yet still too recent to be fully articulated, not only in the first section chronicling those early months alone, but in the third part set exactly one year later. M.’s memory haunts the narrator’s dreams, her attachment to an article of his clothing, his image. However, we learn very little of anything about him or their life together. Likewise, what the narrator is looking for and what she finds is unclear—as in River, it is the journey, or rather journeys, not the destination that guides the narrative.

In the first part of Grove, “Olevano,” one has the sense that the narrator is attempting to find herself in the landscape of a place where death is never far away. Cemeteries, the sellers of fresh and plastic flowers to mark graves, the sight of a body being removed from a house, memories of the Etruscan tombs her father loved, even trees being felled to combat the spread of disease all summon thoughts of morti, followed by sounds of vii—bird song, children’s voices, the daily ordinary routines of life. It’s a slow unfolding, gradual emergence from winter to the early signs of spring, that accompany the narrator’s wandering through the village, the countryside, to Rome, to the sea and back to her temporary refuge on the hillside. She is learning how to live again, awaking in an alien place, a stranger to each new day:

In the first part of Grove, “Olevano,” one has the sense that the narrator is attempting to find herself in the landscape of a place where death is never far away. Cemeteries, the sellers of fresh and plastic flowers to mark graves, the sight of a body being removed from a house, memories of the Etruscan tombs her father loved, even trees being felled to combat the spread of disease all summon thoughts of morti, followed by sounds of vii—bird song, children’s voices, the daily ordinary routines of life. It’s a slow unfolding, gradual emergence from winter to the early signs of spring, that accompany the narrator’s wandering through the village, the countryside, to Rome, to the sea and back to her temporary refuge on the hillside. She is learning how to live again, awaking in an alien place, a stranger to each new day:

When after sweeping the landscape my gaze fell to my hands on the window ledge, I thought I saw M.’s hands beneath them, in the space between my fingers – white and delicate and long, his dying hands, which were so different from his living hands, and they lay beneath mine as if on a double exposed photograph. Then the coffee maker hissed, and the coffee boiled over, and my living hands had to break away from M.’s white hands in order to turn off the stove and remove the pot, but I inevitably burned myself, and this pain made me aware that I hadn’t relearned anything yet.

The flowing language, poetic, careful and observant, traces a slow burning existential pilgrimage. Kinsky paints a rich portrait, not only of the landscape and urban areas, but of the people—from the reticent village population to the groups of African migrants who cluster around marketplaces and bus stations, barely surviving on the outskirts of society, unable to leave, with no home to return to. As in River, a novel set on the edge of London along the Lea River, her narrator here similarly is attentive to the character and quality of place; she does not simply see, she feels her way through the misty months of early disorienting grief and necessary solitude.

I became dizzy looking at this unfurled country which was laid so bare yet remained so incomprehensible to me. A rugged terrain with a restless appearance – it presented itself differently from each side. On each side the routes drew a different script, the mountains cast different shadows, and the plains, foregrounds, midgrounds, and backgrounds shifted. A terrain that left traces in me, without a recognizable trace of myself remaining in it. Something about the relationship between seeing and being seen – between the significance of seeing and being or becoming seen, as a comforting conformation of your existence – suddenly appeared to me as a burning question, which defied all names and acts of naming. If on that hillside some had told me that I might die from the inability to answer or simply even phrase this question, I would have believed them.

It is clear from the beginning that she is no stranger to Italy. Her father spoke Italian, was fascinated with the history of the Etruscans, and year after year family holidays were spent exploring the country. The second section of Grove begins with her father’s death, then revisits memories of trips taken over the years. Grief, through the lens of time and distance becomes an attempt to understand a somewhat elusive man against the backdrop of his knowledge of architectural sites, landscapes and bird calls, his tendency to disappear for hours and his penchant for outings that often led to the family getting lost. In the end though, this fascinating and recognizable account of lengthy family car trips reminds anyone with a similarly enigmatic parent that we can ever fully know them when so much of our experience rests deeply in childhood. Loss and mourning is perhaps always incomplete.

So we come to the third and final part of the novel which finds our narrator returning to Italy exactly one year after her stay in Olevano. Again it is January when a certain colourlessness and frosty otherness mutes the land. She travels first to Ferrara, orienting herself by the landmarks of the life and characters of Georgio Bassani, haunted more by the fictional environs of the Finzi Continis. From there she moves to Comacchio, on the Adriatic, where she spends her days walking through the stark salt pans, observing flamingos and other shore birds, and seeking out the site of a fabled necropolis. It’s a sad and lonely time to be wandering this place devoid as it is of tourist activity, but she seems to be approaching a new, peaceful meditative relationship with loss. If she set out to consider how she might force her life into a new order one year earlier, the apparent bleakness of this last stop in Italy carries the quiet promise of moving forward anew even if where she is heading and what she has learned is not clear, or not for sharing.

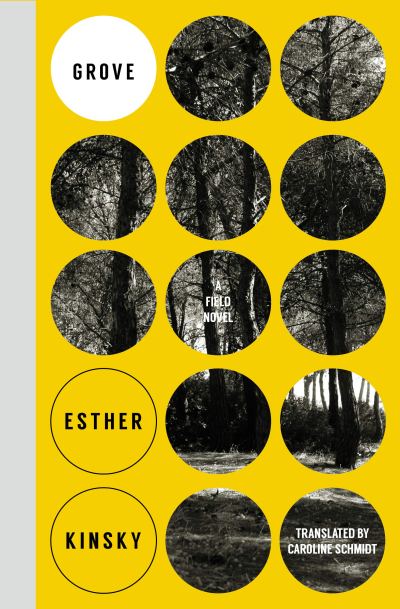

Grove by Esther Kinsky is translated from the German by Caroline Schmidt and published by Fitzcarraldo Editions in the UK and as Grove: A Field Novel by Transit Books in North America.

She writes very powerfully, doesn’t she Joe? And you make a good point about the autofictional element – she *does* keep you at a certain distance, so although she articulates the pain which surely comes from her own loss, it’s in a strongly fictionalised way. A very interesting author.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. I imagine she does draw from real experience but maintains personal boundaries. Much recent auto fiction can lean into too much information IMHO, I like the mystery.

LikeLiked by 1 person