Out into that wondrous night

I stepped unseen and stealthy,

with not a thing in my sight

nor any light to guide me

but one burning in me bright.(from “On a Dark Night” by Saint John of the Cross)

If Fray Juan, the determined and devout evangelist of the barefoot or Discalced Carmelites, the reformed order founded by Saint Teresa of Ávila, was deemed troublesome during his lifetime, the humble Spanish friar, poet and mystic who would later become known as San Juan de la Cruz or, in English, Saint John of the Cross, was no less disruptive in the months and years that followed his death. In life, his dedication to the austere principles of the reformed order and his success in fostering it’s expansion across sixteenth century Spain upset other Carmelites. In 1577, this led to his torture and confinement in a monastery in Toledo where he composed and committed to memory one of his best loved poems prior to making his daring escape, naked into the “pitch-dark night.” After recovering from his ordeal, he returned to assisting with the spread of chapters of the Discalced Carmelite before eventually joining the monastery in Segovia as prior. Yet, when he disagreed with some changes being made in his order, he was moved to an isolated location where he fell ill with erysipelas. As his condition worsened, he was transferred to the monastery in Úbeda where he died on December 14, 1591 at the age of forty-nine. However, he would not stay there, well, at least not in one piece. The widow doña Ana de Peñalosa, sister of the influential don Luis de Mercado who was Fray Juan’s friend and the funder of the monastery in Segovia, wanted his remains to rest there.

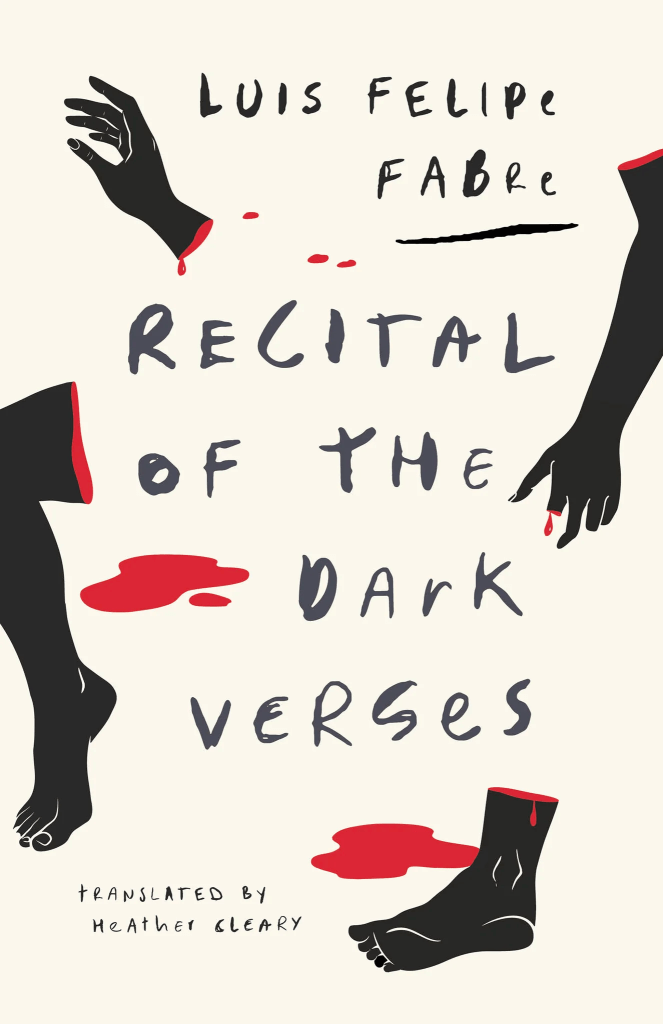

The effort to satisfy that desire is where Mexican writer Luis Felipe Fabre’s Recital of the Dark Verses begins. What follows is an unexpectedly energetic historical-fiction-meets-comic-road-novel that serves up spirituality, adventure, with a healthy amount of bawdy humour. When the bailiff, whose name biographical sources fail to agree on, and his two young assistants, Ferrán and Diego (thus named because no record exists to confirm or contradict the author’s fancy), arrived at the monastery in Úbeda in September or October of 1592 with orders to collected the late friar’s body, they are met with no small measure of resistance. First there’s the matter of the smell emanating from the corpse that has inspired ecstasy in the monks and near frenzy among the townsfolk who have clamoured for any available piece of Fray Juan’s tattered clothing, soiled dressings, or physical person. As the porter explains to Diego and Ferrán, it is a question of:

“The aromatic clamor of his body. The scent of saintliness. The gentlest of perfumes which stirs in the soul yearnings, burnings, and zeal, and which, emanating from beneath the slab whereunder lies Fray Juan and drifting through the air, at times reaches my own nose like a distant jasmine while at this door I stand.”

It is a scent that cannot be silenced, an aroma that inspires a devotion so intense that it can lead to feverish displays of ardor or, if one fears being deprived of access to it, potential violence. Of course, for those who cannot smell it, or who only detect the normal odour of decay, it can engender doubt and fear about the solidity of one’s own faith.

But that is not all that delays the planned retrieval. When it is uncovered eight or nine months after the friar’s demise, the body Fray Juan, even with all the sores caused by the disease that killed him, is uncorrupted. A finger cut off still draws blood. So the bailiff takes the finger as a token for doña Ana, and instructs the monks to make an effort to encourage some further desiccation, vowing to return the next year. So it is not until April of 1593, that the bailiff and his assistants finally manage to depart Úbeda with the body of Fray Juan in a large leather case—albeit absent an arm left behind as relic. They travel by night, staying off the main roads, but they cannot escape the saintly scent, impossible to disguise, that arises from their secret cargo and which will be responsible for much of the undue attention and danger that will stalk them as they seek to carry out their mission.

Along the way they not only have to face their own fears as the dark nights threaten to close in around them, they must fend off amorous barmaids, a group of shepherds with ill intent, and an angry mob of townsfolk from Úbeda who are determined to retrieve the body of their blessed friar at all costs. Fabre draws on a wealth of often conflicting historical and biographical accounts of the saint’s posthumous journey, while liberally incorporating themes and figures from Greek mythology. But fundamental to this absurd tale of devotion, temptation, and misadventure are the words of San Juan de la Cruz himself. Three of his best known poems—“On a Dark Night,” “Love’s Living Flame” and “Spiritual Canticle”—are recited in full or in part throughout the novel, along with passages from the extensive commentaries the friar wrote to flesh out his own work.

For a man so committed to an especially extreme expression of faith, Fray Juan’s verse is intensely passionate and sensual in nature, with a speaker that often takes on a female voice, that of a lover seeking to join with her Beloved. The spiritual ecstasy inspired by his words contrasted with the religious attachment his followers hold to his physical body (which will not make it to Segovia fully intact—only his head and torso rest there to this day), set the stage for a philosophical exploration of the blurred line between the heavenly and the worldly domains. On their journey, the three couriers tasked with the transportation of the friar’s body, will all face their own demons. The bailiff doubts his faith, while twenty-year-old Ferrán, who is trying to stay one step ahead of the Inquisition is cynical and unmoved by the mystic’s poetry. However, sixteen year-old Diego, a naive youth in the full turmoil of puberty, finds his tongue possessed by Fray Juan’s words and his soul struggling to balance spiritual inspiration with his own blossoming sexuality:

He was delirious. Delirious with fear, with fever, with hunger, exhaustion, and love. But through his deliria did Diego speak truth as if by the tongue of another. For his deliria were none other than Fray Juan’s liras and, though Diego knew them not, from him did they spring forth as if from an old and distant void or night or heart.

The result is a tale that is light in tone, but one that easily carries deeper and darker themes on its playful narrative stream. Careful attention is paid to the exegetic tradition and the formal conventions of the saint’s own commentaries. Each chapter opens with an introduction incorporating the specific lines that will be expanded upon therein along with the particular challenges that await our protagonists. To further evoke the mood of the era, Fabre, in the original Spanish text, employs certain archaic verb forms and syntax. Translator Heather Cleary, unable to access exactly the same measures, choses to:

play with word order, an antiquated past tense, and a few lexical choices here and there in order to create similar rhythmic effects, shift the temporality of the narrative without sacrificing clarity, and evoke the ludic sensibility that evades the original.

It works beautifully. The result is a comic Golden Age-hued celebration of the many questions that can arise about the nature of the relationship between the body and the soul, the sacred and the profane. You can take any answers it may suggest as you will.

Recital of the Dark Verses by Luis Felipe Fabre is translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary and published by Deep Vellum. This book was read as part of Spanish Lit Month 2024.

Well, I was wondering how that cover would fit, but it most definitely does! What a tale.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s the perfect balance of absurdity, philosophy, and history (insofar as contemporary biographies of would-e saints can be). The obsession with relics—even body parts—in the Church confounds me, but St John really was divided up along the way to his final resting place!

LikeLike