all paths

lead to the same place

journey is illusion’s horsebackthe world’s embers

blacken its wanton footstepthey burn

our anxious tongueswithin its form

the poem seeks itself

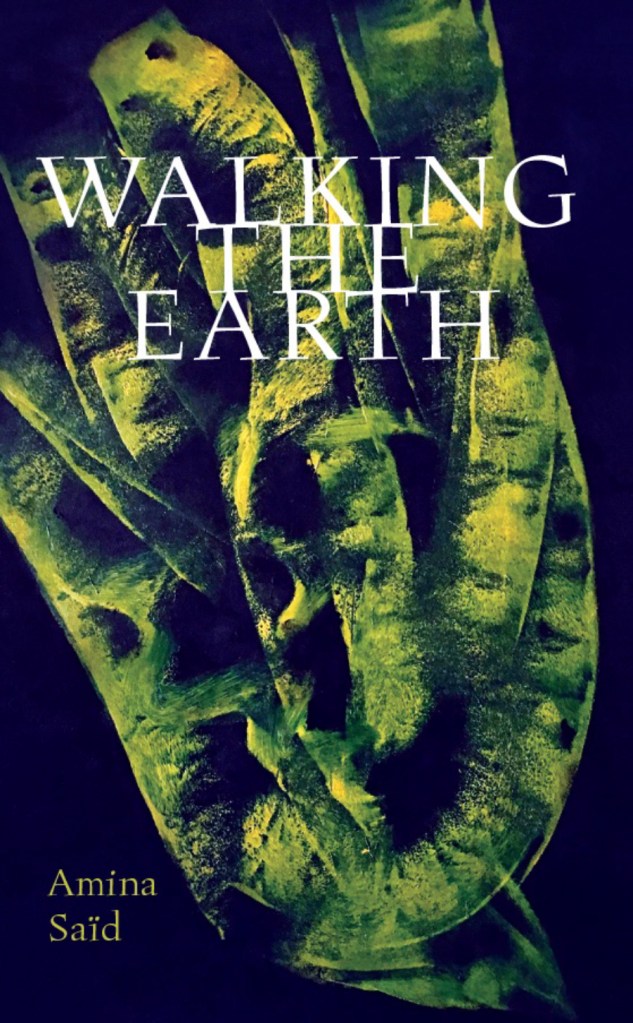

Poems for wanderers, or the poem as a series of wandering, emergent forces, Walking the Earth by Amina Saïd hums with an intoxicating, primal energy that speaks to something fundamentally vital and human, in a sense that is too easily buried in the noise and chaos of our constantly plugged-in contemporary reality. Born in Tunisia in 1953, to a French mother and Tunisian father, Saïd was raised in both Arabic and French. At the age of sixteen she moved to Paris with her family where, when she entered university, she decided to study English literature so not to have to choose between her two native languages. Her poetic vision, however, draws on French and Arabic sources and the sunlit Mediterranean landscapes of her birthplace.

Today, Saïd can be considered, according to Hédi Abdel Jaouad, the author of the Preface present text, as the “most potent—and prolific—poetic voice in Tunisia today, if not in the whole of Francophone Africa.” Yet, until this point, no complete, single volume of her work has been made available in English. Now, thirty years after its original 1994 release, Walking the Earth (Marche sur la terre), in Peter Thompson’s translation, finally corrects this oversight.

Today, Saïd can be considered, according to Hédi Abdel Jaouad, the author of the Preface present text, as the “most potent—and prolific—poetic voice in Tunisia today, if not in the whole of Francophone Africa.” Yet, until this point, no complete, single volume of her work has been made available in English. Now, thirty years after its original 1994 release, Walking the Earth (Marche sur la terre), in Peter Thompson’s translation, finally corrects this oversight.

This haunting sequence of poems, untitled and distinguished only occasionally by dedications, or by shifts in format or theme, has a hushed meditative quality reinforced by the poet’s spare, concise language, subdued and mystical tone, and the recurrence of common motifs. The world her speakers evoke is shaped by primordial elements in concert with journeys across a vast unformed terrain:

earth is this round dream

in its heart

stones fusingtheir fire tongues

gouge the pathways of blood

where another fire burns

In her prefatory Note, Saïd writes that this, her seventh book, can be understood as a search for “place”—one that moves from the intimate to the universal—her own journey and that of many who pass through spaces “as much geographical as mental.” She is thinking of the displaced, those driven to move by war or disaster, but also the wanderer and traveller. Wandering is a theme of particular importance in Maghrebi (Northwest African) literature, and one that touches the poet, as someone who writes to hold an intermediary space between the Orient and the Occident, deeply:

My belonging to these two worlds both legitimizes the quest for place and generates a proliferation of doubles: shadows, voices, witnesses, angels, those who keep vigil. . .

This quest for place is born of a profound feeling of exile. Isn’t any creative person “exiled,” a nomad, an eternal wanderer seeking a place—a utopia, a place imaginary, impossible, dreamed of—which poetry can, with a sudden flaring, show in an unforeseeable image?

The quest that stretches across the pages of Walking the Earth is rich in mythological and archetypal images. The recurrence of specific motifs—light, darkness, stones, deserts, shorelines, blood, fire, tongues, voices, screams, silence—contributes to the cyclical feel of the work. Walking is an existential act while language and words are formative elements:

a voice recites

a voice despairs

the choir takes hearta hand inscribes

ancient alphabetsthe light awakens

As the sequence progresses, it becomes clear that the search for “place” is ultimately a search for meaning. The poem itself is the journey, even if the end is but another beginning. It is a path a reader can walk over and over again, and arrive at a different “place” each time.

the poem scents itself

with deepest nightI inscribe myself with sand and dust

in the nostalgia of a world

from before this worldI’m absent

from the mirror of the tribe

Walking the Earth by Amina Saïd is translated from the French by Peter Thompson with a Preface by Hédi Abdel Jaouad and published by Contra Mundum Press.