Anyone familiar with the unbroken, single paragraph monologues that characterize the typical novel by late Austrian writer, Thomas Bernhard, might find it hard to imagine how his work could be realized in the medium of the graphic novel. I mean wouldn’t there be too many words to corral on the blank page? How could the intensity of the original be translated? For Austrian cartoonist and animator Nicolas Mahler it’s simply a matter of focusing on the essentials of the story and letting his quirky illustrations and creative use of space do the rest. As a result, his graphic interpretation of Bernhard’s Old Masters: A Comedy is, well, something of a small masterpiece. One suspects that the author himself, and his alter ego characters, Reger and Atzbacher, would secretly agree, despite their shared conviction that a true artistic masterpiece is impossible to achieve, let alone imagine.

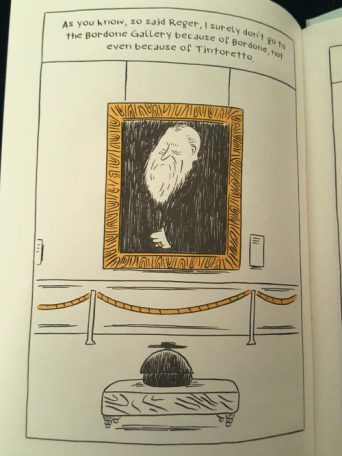

Rendered in stark black and white drawings playing on extremes—massive architectural details, characters who are tiny and squat, elongated and thin, or large and corpulent, often grotesque, appear against golden yellow highlights (a distant echo of the artwork in Ludwig Bemelmans’ Madeline series)—Mahler allows his images to complement and amplify the ridicule, humour and disgust so intrinsic to this and the majority of Bernhard’s idiosyncratic prose. Frequently recurring of images—the museum security guard, Irrsigler, seems to spend an inordinate amount of time disappearing into the men’s room—visually mimic Bernhard’s fondness for repeating phrases and motifs. As the blurb on the back of the newly released English language translation of this comic-book take on a comic classic states: “The Master of Overstatement meets the Master of Understatement.”

Rendered in stark black and white drawings playing on extremes—massive architectural details, characters who are tiny and squat, elongated and thin, or large and corpulent, often grotesque, appear against golden yellow highlights (a distant echo of the artwork in Ludwig Bemelmans’ Madeline series)—Mahler allows his images to complement and amplify the ridicule, humour and disgust so intrinsic to this and the majority of Bernhard’s idiosyncratic prose. Frequently recurring of images—the museum security guard, Irrsigler, seems to spend an inordinate amount of time disappearing into the men’s room—visually mimic Bernhard’s fondness for repeating phrases and motifs. As the blurb on the back of the newly released English language translation of this comic-book take on a comic classic states: “The Master of Overstatement meets the Master of Understatement.”

And it’s a match made in, well, the Art History Museum in Vienna.

There is precious little action in Old Masters and little obvious plot. It is, however, a spirited takedown of Bernhard’s favourite targets: the Catholic Church, the State, the arts and artists—his characteristically dark, satirical look at the world in general and Viennese society in particular. But it is also, in the end, a touching, sad and surprisingly romantic tale.

The story unfolds, if you will, at the musem, on a bench in the “so-called Bordone Gallery” directly across from Tintoretto’s White-Bearded Man. Here sits Reger, as he is wont to do every other day. Meanwhile, the narrator, his long-time friend Atbacher, observes him, just out of sight, from the “so-called Sebastiano Gallery” waiting for exactly eleven thirty, the time at which the two men have agreed to meet. Reger’s invitation is out of character because the they had met there just the day before and this second consecutive rendezvous was not in keeping with the typical pattern of either man. Curious as to the reason for Reger’s invitation to break from habit, Atbacher has arrived an hour early so as to watch his friend undetected. Naturally, this provides him the opportunity to launch into a lengthy account of Reger’s family history, his opinionated views, and his predilection to spend every other day at the museum, seated across from Tintoretto’s White-Bearded Man. In the novel this monologue consumes the bulk of the text. The same is true in this version which contains roughly the same number of pages, but much, much fewer words!

The story unfolds, if you will, at the musem, on a bench in the “so-called Bordone Gallery” directly across from Tintoretto’s White-Bearded Man. Here sits Reger, as he is wont to do every other day. Meanwhile, the narrator, his long-time friend Atbacher, observes him, just out of sight, from the “so-called Sebastiano Gallery” waiting for exactly eleven thirty, the time at which the two men have agreed to meet. Reger’s invitation is out of character because the they had met there just the day before and this second consecutive rendezvous was not in keeping with the typical pattern of either man. Curious as to the reason for Reger’s invitation to break from habit, Atbacher has arrived an hour early so as to watch his friend undetected. Naturally, this provides him the opportunity to launch into a lengthy account of Reger’s family history, his opinionated views, and his predilection to spend every other day at the museum, seated across from Tintoretto’s White-Bearded Man. In the novel this monologue consumes the bulk of the text. The same is true in this version which contains roughly the same number of pages, but much, much fewer words! We learn that Reger, the museum regular, has been visiting the Art History Museum for over three decades. Yet his attitude toward great art, the work of the “so-called” old masters, is one of disdain. Philosophically, he muses that a detail might be perfected, but the whole of any painting, sculpture, or other artwork ultimately leaves us appalled:

We learn that Reger, the museum regular, has been visiting the Art History Museum for over three decades. Yet his attitude toward great art, the work of the “so-called” old masters, is one of disdain. Philosophically, he muses that a detail might be perfected, but the whole of any painting, sculpture, or other artwork ultimately leaves us appalled:

There is no perfect painting and there is no perfect book and there is no perfect piece of music, said Reger, that is the truth.

None of these world-famous masterpieces, no matter who did them, is actually something whole and perfect. That reassures me, he said. In essence, this makes me happy.

Only when we unswervingly come to the realization that there isn’t this whole or perfect thing do we have a possibility of survival.

And that has been the reason why I have gone to the Art History Museum for over thirty years…

As one might a expect, a number of artists, writers, and thinkers are subject harsh, and often hilarious, criticism as Reger, speaking through Atbacher’s account, expresses his unbridled opinions. Nineteenth century Austrian author, Adalbert Stifter, for example, is written off as a “kitsch master” with “enough kitsch on any random page to satisfy more than one generation of poetry-thirsty nuns and nurses” and then, strangely, compared to Heidegger, that “National Socialist, knickerbocker-wearing Philistine.” No one tosses out an insult like a cranky Bernhard character!There is, of course, much more below the surface than insults and irritation. That is where his peculiar wisdom lies. And, in this story, we learn that our irascible main character Reger’s antipathy to the old masters, and artists in general, has its roots in an emptiness they cannot fill. One that speaks to his, and our, need for love. One does not need to be familiar with Old Masters in its original form to enjoy this book (I wasn’t), but exposure to Bernhard in his full verbal intensity probably is. The satire, the heartbreaking warmth of the ending, and the sheer feat of rendering the mood and spirit of the Austrian writer’s pessimism and bleak humour into a graphic novel is not likely to be fully appreciated otherwise. I am a huge admirer of Bernhard, but I confess I’ve never really been drawn to graphic novels (pardon the pun). But the other night, when my son found this book on the doorstep of my old house where it had been left by a courier, I was immediately captivated. It has been a difficult few weeks and Bernhard’s misanthropic humour, oddly, is always strange comfort at such times. The beauty of this book is that it is not only a delight to read and look at, but I can imagine myself returning to it and rereading it many times (after all it doesn’t take very long—it’s akin to an instant hit of Bernhard relief).

One does not need to be familiar with Old Masters in its original form to enjoy this book (I wasn’t), but exposure to Bernhard in his full verbal intensity probably is. The satire, the heartbreaking warmth of the ending, and the sheer feat of rendering the mood and spirit of the Austrian writer’s pessimism and bleak humour into a graphic novel is not likely to be fully appreciated otherwise. I am a huge admirer of Bernhard, but I confess I’ve never really been drawn to graphic novels (pardon the pun). But the other night, when my son found this book on the doorstep of my old house where it had been left by a courier, I was immediately captivated. It has been a difficult few weeks and Bernhard’s misanthropic humour, oddly, is always strange comfort at such times. The beauty of this book is that it is not only a delight to read and look at, but I can imagine myself returning to it and rereading it many times (after all it doesn’t take very long—it’s akin to an instant hit of Bernhard relief).

Thomas Bernhard’s Old Masters, illustrated by Nicolas Mahler, is translated from the German by James Reidel, and published by Seagull Books. Essential medicine for any Bernhard fan, I’d say.

This is my first offering for German Literature Month 2018.

You know, I might just be tempted by this…

I’ve only read Concrete, but I liked it, so maybe this one might suit me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This might just be my way into Bernhard …

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is a lot of fun. I’d like to read the novel now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really never expected to enjoy a graphic novel so much, but this one is definitely one for me!

LikeLike

I just read for GL 8 The Loser by Thomas Bernhard. A typical long monologue attacking everything. The story line revolves around The influence The Canadian Piano Master Glenn Gould had on The musical ambitions of The narrator and a friend. I would suggest those new to Bernhard start with Wittgenstein’s Nephew

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Loser was my first Bernhard, and I love Wittgenstein’s Nephew. I usually recommend Gargoyles as a starting point, but in truth I really like his short works: Voice Imitator and Goethe Dies in particular.

LikeLike

What an intriguing idea. Wonder what B himself would think of it? I’ve had Correction sitting accusingly on my nightstand for ages, and have never felt sufficiently morose to start it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t help but think he would like it. Beneath the dark satire we associate with him is a great degree of humour and affection. What puts me off some of his longer novels is simply the unbroken deluge of words—my reading time is often too fragmented to allow me to get caught up in that. I am very fond of his shorter works which condense his style into novellas, stories, even “flash” fiction. This project allows for the incorporation of the “deeper” questions that exist in his longer works into a work that can be read in a much shorter time.

LikeLike

Thanks for highlighting this one. It’s certainly an intriguing concept, although I would never have expected to see a graphic adaptation of any of Bernhard’s novels. Despite conjuring up fairly vivid mental images of his characters and settings while reading, I’ve always considered his treatment of these elements to be muted and rather secondary to the monologues that dominate his texts. But I suppose this might represent a welcome challenge to an artist interested in adaptation of his work into a visual medium.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s clearly created with a great deal of respect and admiration for Bernhard’s work. Not being a graphic novel aficionado, I can only judge it by my own response. It’s great fun!

LikeLiked by 1 person

How fascinating! I’ve never read any of Bernhard’s work, but I confess this is very tempting… 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Might be a good way to start—read this and then the novel it is based on.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an inventive project and a nice gateway into the work of Thomas Bernhard. Added to my TBR, and looking forward to your future contributions to German Literature Month, Joe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. As usual, I have grand ambitions and lots of German lit to chose from, but I’ll be happy if I manage a few good contributions.

LikeLike

Really glad you persuaded me to pick this up, Joe. Just the thing for an off-colour day. Don’t think I’ll review because you have done such a sterling job. I might – just might – proceed to the novel now, though I’m still not sure if I can handle Bernhard in all his diatribic intensity!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, that is quite an achievement, would never have thought of Bernhard as graphic novel material…

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s great, and clearly created with a lot of affection for Bernhard. I’ve never thought of myself as a graphic novel reader, but this works for me, perhaps because it is Bernhard!

LikeLiked by 1 person