We live in a world that is always in flux. Conflict, natural disasters, and political destabilization are continually reshaping our world and threatening our future on an intimate, community and global scale. An element of the universality of the human condition unites us in our response to these factors while privilege, culture, and history set us apart. To begin to understand where others have come from, what they have been through, their trials and their dreams, we must be able to speak to one another, learn to listen, and read their words. This is why translation matters.

The art of literary translation is often said to be both impossible and necessary. Impossible because no linguistic code is commensurable with any other—particularly so in the case of poetic language which, being among the most refined and expressive of literary forms, is expected to have myriad and complex nuances. Yet translation remains necessary. Without it there would be no conversation across linguistic and cultural barriers, no prospect of the mutual understanding that remains a prerequisite for the peaceful, emancipated life towards which we are all striving.

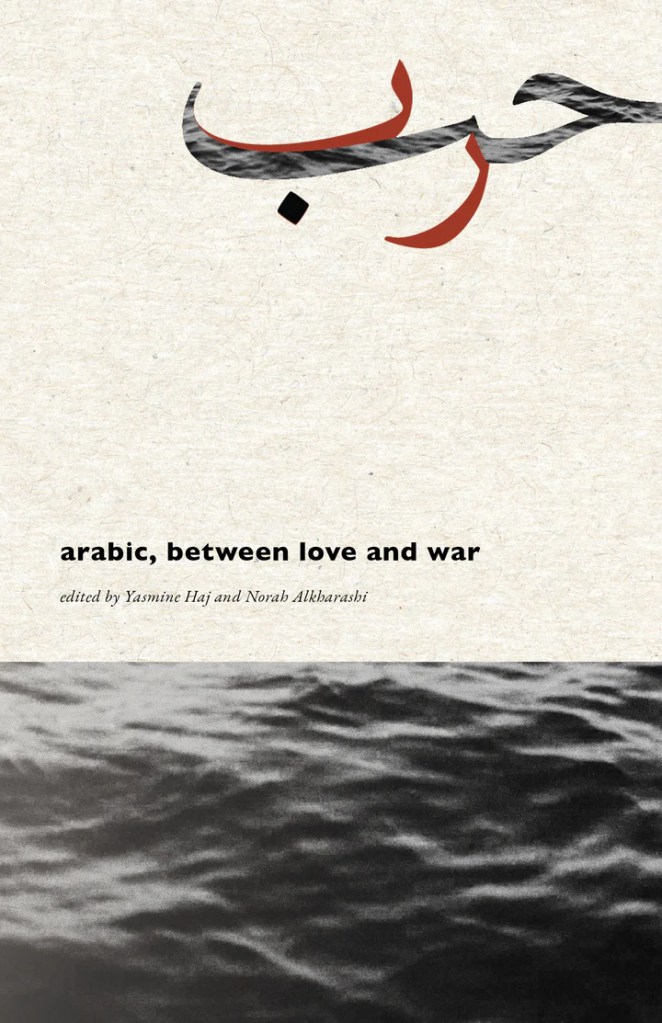

These are the words of translator and scholar Norah Alkharashi from her introduction to arabic, between love and war, a distinctive collection of poetry co-edited with Yasmine Haj and newly released by the independent Canadian publisher trace press. This anthology, which gathers the work of poets and translators from across the Arabic speaking world and its diaspora, arose from a series of creative translation workshops, facilitated by the editors, that allowed translators from varying backgrounds the time and space to explore the “processes of loss and unlearning encountered on their path to translation as critical creation.” This unique collaborative engagement ultimately led to the selection of thirty-seven thematically linked poems, presented alongside their translations—Arabic to English or English to Arabic—that comprise the first release in the trace: translating [x] series.

The title and theme of this project illustrates one of the central challenges of the art of translation: how to reflect the nuances implicit in one language within the context of another. In Arabic, only one extra letter separates the word for “love” حب from the word for “war” حرب , a distinction that can have many implications in poetic discourse, especially when the two realities are often so deeply entwined in the lived experience of so many in the Arabic speaking world. Here the collected poems are divided into three sections: Love, Interval, and War, but the boundaries cannot be so clearly drawn. War frequently lingers in the background, even when a poet speaks of love; while love is a persistent life force even in the face of loss, loneliness, and displacement. And once again, the memory and fear of war haunts, even in the quiet in between conflicts—in the interval.

The title and theme of this project illustrates one of the central challenges of the art of translation: how to reflect the nuances implicit in one language within the context of another. In Arabic, only one extra letter separates the word for “love” حب from the word for “war” حرب , a distinction that can have many implications in poetic discourse, especially when the two realities are often so deeply entwined in the lived experience of so many in the Arabic speaking world. Here the collected poems are divided into three sections: Love, Interval, and War, but the boundaries cannot be so clearly drawn. War frequently lingers in the background, even when a poet speaks of love; while love is a persistent life force even in the face of loss, loneliness, and displacement. And once again, the memory and fear of war haunts, even in the quiet in between conflicts—in the interval.

The poems of the first section, “Love,” tend to be tinged with sadness and longing, be it for for an imprisoned child or a lost lover:

I remembered you!

. I remembered the silence growing slightly wet,

. and the trees that shaded us,

. and the fragrance drawing near.. I didn’t know

that we were on the edge of everything

and that one word

alone was enough to wither a tree,

. that silence turns into shade,

. and the heart a safe haven for pain.– from “One Word” by Ali Mahmoud Khudayyir

Translated from Arabic by Zeena Faulk

Meanwhile, the longest section, “Intervals,” casts the widest emotional net, speaking to the most fundamental elements of human experience—birth, death, hope, despair—in a world that can seem to turn without reason, or as the epigraph to this part says, those “liminal spaces where wars of flesh and love—ongoing, past, or yet to pass—have lingered. Holding hearts and words in limbo, with beats yet to be translated.” Lena Khalaf Tuffaha’s “Time Travel,” originally written in English, captures this unsettled sense succinctly:

. . . We travel because

motion is more comfortthan settling, calcifying.

We travel because it meanswe haven’t gotten to where

we’re going yet, the storyis still being written and

our fractures aren’t done setting.There is still a chance

we’ll turn out differentor better or—best of all—

like our parents withoutknowing we’ve become

who they were. . .

Finally, it is sadly no surprise that the poems in the “War” section are the most direct and unequivocal. But they are not without a promise, however faint, and hope for a future free from the ravages of war:

I wish I could, I wish it were in my hands

to uproot injustice

and dry the rivers of blood

off this planet.

I wish I could, I wish it were in my hands,

to hold for this man, tired

in the path of confusion and sorrow,

a lamp of prosperity and serenity

and grant him a safe life.

I wish I could, I wish it were in my hands,

yet all I have at hand is a ‘but’.– from “This Earthly Planet” by Fadwa Tuqan

Translated from Arabic by Eman Abukhadra

These are but three brief excerpts. The poems gathered here represent the work of fifteen poets chosen for translation by fourteen translators (some translate more than one poet or are also poets themselves), and together the contributors come from varied Palestinian, Iraqi, Jordanian, Saudi Arabian, Lebanese, Sudanese, Tunisian, Egyptian, Syrian, Canadian, American and British backgrounds. Some of the poets write in English (and are thus translated into Arabic), whereas some of the translators are scholars specializing in Arabic. This rich range of perspectives and differing Arabic literary traditions must have contributed to a vibrant workshop environment which is distilled in this elegant and vital anthology.

arabic, between love and war is edited by Yasmine Haj and Norah Alkharashi, and published by trace press.