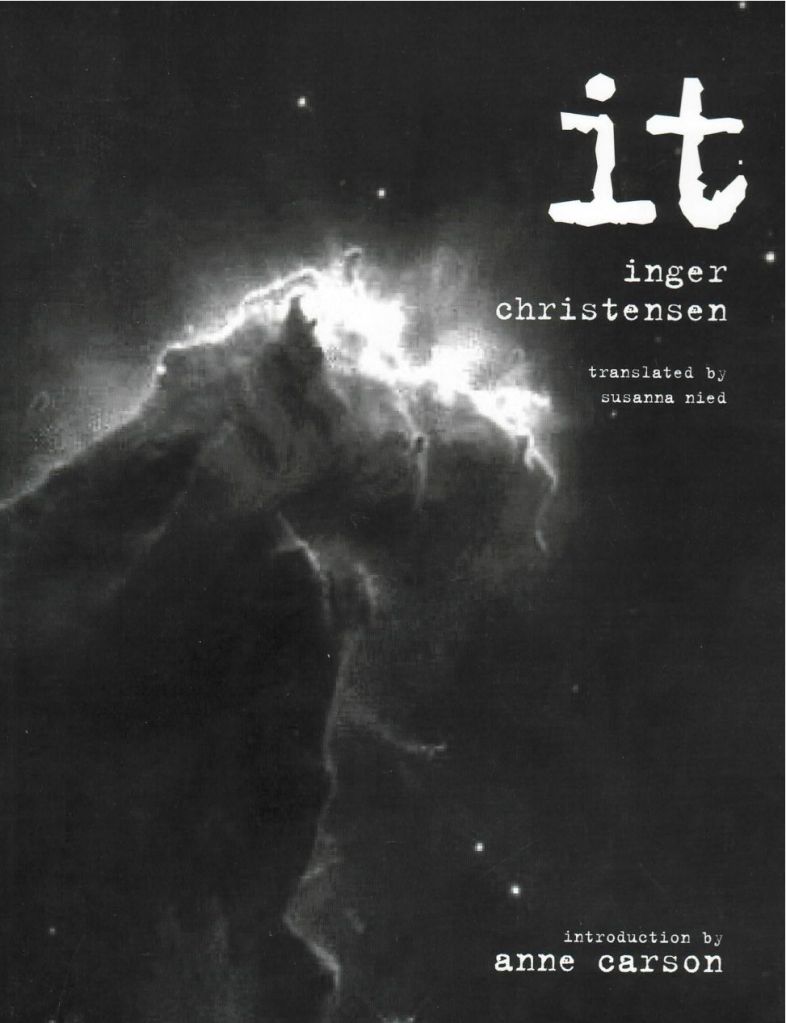

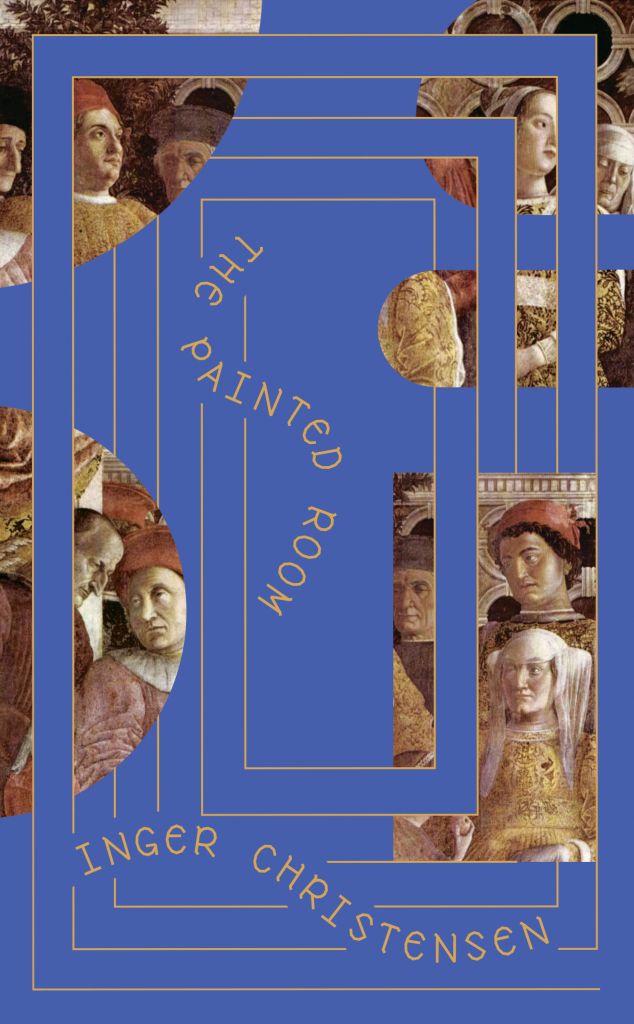

Recently re-issued by New Directions, Denise Newman’s translation of Inger Christensen’s 1976 novella The Painted Room might at first appear to be somewhat more conventional than the Danish poet’s experimental prose works like Azorno or Natalja’s Stories. That would, of course, be a premature assessment. Subtitled A Tale of Mantua, this slender three-part volume is set in, and revolves around, the court of Ludovico Gonzaga III and the painting of the famous Bridal Chamber by Andrea Mantegna in the mid-1400s, but it is more than a simple piece of historical fiction. By turns witty, magical, and wise, The Painted Room offers a pointed commentary on art and immortality, power and passion.

As Italy gradually splintered following the fall of the Roman Empire, it evolved into a patchwork of independent territories over which powerful families battled for control until, by the fifteenth century it was common for each of these regions to be held under the autocratic control of single princes. Mantua in northern Italy, ruled by the Gonzaga’s from 1328 to 1707, was not only a tyrannical, war-focused principality, but, as its ruling family sought to elevate its social status through patronage of the arts, architecture, and music, it would become an important cultural centre in the early years of the Renaissance. In 1459, acclaimed artist Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), noted for his striking compositions and innovative studies of perspective, agreed to enter into the service of Ludovico, the Marquis of Mantua, and the following year he was appointed court painter—a position he would hold for over forty years. His masterpiece would be completed there, the Camera degli Sposi or The Bridal Chamber in the ducal palace, a room decorated with realistic architectural details, frescoes featuring interrelated narratives and a spectacular illusionary ceiling that appears to be a concave structure with an oculus open to the sky. The painting of this room and its images, offer the inspiration for Christensen’s novel, but the story she weaves extends far beyond these four walls.

As Italy gradually splintered following the fall of the Roman Empire, it evolved into a patchwork of independent territories over which powerful families battled for control until, by the fifteenth century it was common for each of these regions to be held under the autocratic control of single princes. Mantua in northern Italy, ruled by the Gonzaga’s from 1328 to 1707, was not only a tyrannical, war-focused principality, but, as its ruling family sought to elevate its social status through patronage of the arts, architecture, and music, it would become an important cultural centre in the early years of the Renaissance. In 1459, acclaimed artist Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), noted for his striking compositions and innovative studies of perspective, agreed to enter into the service of Ludovico, the Marquis of Mantua, and the following year he was appointed court painter—a position he would hold for over forty years. His masterpiece would be completed there, the Camera degli Sposi or The Bridal Chamber in the ducal palace, a room decorated with realistic architectural details, frescoes featuring interrelated narratives and a spectacular illusionary ceiling that appears to be a concave structure with an oculus open to the sky. The painting of this room and its images, offer the inspiration for Christensen’s novel, but the story she weaves extends far beyond these four walls.

The first part, “The Diaries of Marsilio Andraesi: a selection” proports to be outtakes from the personal journal of Ludovico’s devoted secretary, pictured to the far left of the Bridal Chamber’s “court scene” fresco which features members of the Gonzaga family and their attendants. Here Andraesi is leaning in to listen to the prince who has turned to speak to him. From the secretary’s personal account, which begins in March of 1454, we get an unvarnished, if rather biased and often catty, record of events leading up to Mantegna’s arrival at Mantua through to his death in 1506. Andraesi is not impressed with his master’s persistent efforts to woo the celebrated artist and the reason for his resistance is unlikely. It seems that the painter’s wife, Nicolosia Bellini (of the Venetian artistic dynasty), was once his secret love, now forever lost. So he focuses his attention on rumours he’s heard of Mantegna’s reputation as a troublemaker trained in “arrogance, brutality, and the hunt for novelty.” He feels the prince’s idolatry will only lead to shame. But, of course, the offer is accepted and the secretary’s would-be romantic rival arrives, at first on his own, but soon followed by his family:

Today I finally caught a glimpse of Nicolosia. I became deathly pale and could barely move. My brain turned completely white and my heart so drained of blood that it could hardly beat; I froze. An angel in the fire of earthly feelings.

(17th of August, 1460)

Bitterness and jealously continue to colour Andraesi’s reports, especially as progress on decorating the palace room is slow, and his secret confrontations with Nicolosia intensify. Then, when Mantegna’s wife suddenly dies (at least in this version of reality), the relationship between the two men gradually begins to shift toward what will eventually become one of friendship and respect. In the meantime, Mantegna’s young children are devastated by the loss of their mother but comforted by their father’s inclusion of her likeness in his art. After all, in art, the dead live on. When the frescoes are finally completed in 1474, guests are welcomed for a dedication event in what Ludovico calls “The Painted Room,” but which the children have christened the “Ghost Room.” In his reflections on the occasion, Andraesi calls attention to the uncomfortable dynamic that exists between art and immortality:

There is more life in the paintings than in all of these lively and rapturous spectators who simply put on airs because they are afraid of the pictures’ soul which is their own. The pictures are like all great ghosts in Art who calmly and tirelessly wait for their living models to die. All those who have had the chance on this occasion to look at themselves in the light of Art’s exegesis have consequently entered into a relationship with Death; and they must each conduct their negotiations with him day by day over the time and place and manner of their dying, and about their measure of anxiety.

In the second part, Christensen’s narrative adopts an even more fantastic examination of life at court and its connections to the broader world. However, immortality continues to be a central theme, not explicitly through art but through children, legitimate or otherwise. Attention turns to the dwarf depicted in the “court scene,” a member of the prince’s entourage, re-imagined as Ludovico’s daughter and given the name Nana (Italian for dwarf). When we meet her she is distraught about her unfortunate fate, imagining that her diminutive height will deny her an opportunity to love and marry. The gardener steps in and arranges for her to marry his beautiful son Piero once they are both old enough.

Nana’s story adds an added dimension to the events recounted in the first part. On the day of her wedding three unknown women appear; no one is certain who they are but coincidentally Mantenga has captured their likenesses among the figures who are seen leaning over the balustrade that surrounds the oculus painted on the ceiling of the so-called Ghost Room. To Nana, they are clearly angels. They tell her that Piero is actually the son of Pope Pius II, and leave her what she calls “The Angel’s Book,” a volume that is in fact the popular erotic novel written by the Pope before his call to the priesthood, when he was known y his birth name, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini. The Tale of Two Lovers tells of the tragic affair of Euryalus, one of the men waiting on a nobleman and Lucretia, the wife of a wealthy man. Their love is expressed through a series of letters until they are finally able to meet in bed. Variations on the theme of this tale are echoed and played upon as The Painted Room unfolds, along with the revelation of other surprising entanglements.

The final, dreamlike part of The Painted Room takes the form of a “how I spent my summer holidays” school assignment written by Bernadino, the then ten year-old son of Mantega. He details his role in assisting his father in his work on his masterpiece, describing much of the process involved in laying the foundation, and mixing and applying the paints. But then he realizes that he is expected to record some kind of trip or adventure when in truth he has gone nowhere. So taking inspiration from his younger sister, he imagines himself entering the background of one of his father’s paintings and meeting an aged Greco-Roman hero who has forgotten who he is. Yet another glance at the question of immortality through the daydreams of a child facilitated by the magic of art.

Inger Christensen’s fiction—and her poetry for that matter—tends to work with layers, variations, and cross-referenced themes. Her foray into the world of fifteenth century Italian court life is filled with art, intrigue, infidelity, and murder, blending fact and fantasy to create an informative, entertaining, and intelligent tale. And, like any one of Mantegna’s famous paintings, repeated visits and closer inspection promises to offer ever more detail and connections.

The Painted Room by Inger Christensen is translated from the Danish by Denise Newman and published by New Directions.