A form of life that keeps itself in relation to a poetic practice, however that may be, is always in the studio, always in the studio.

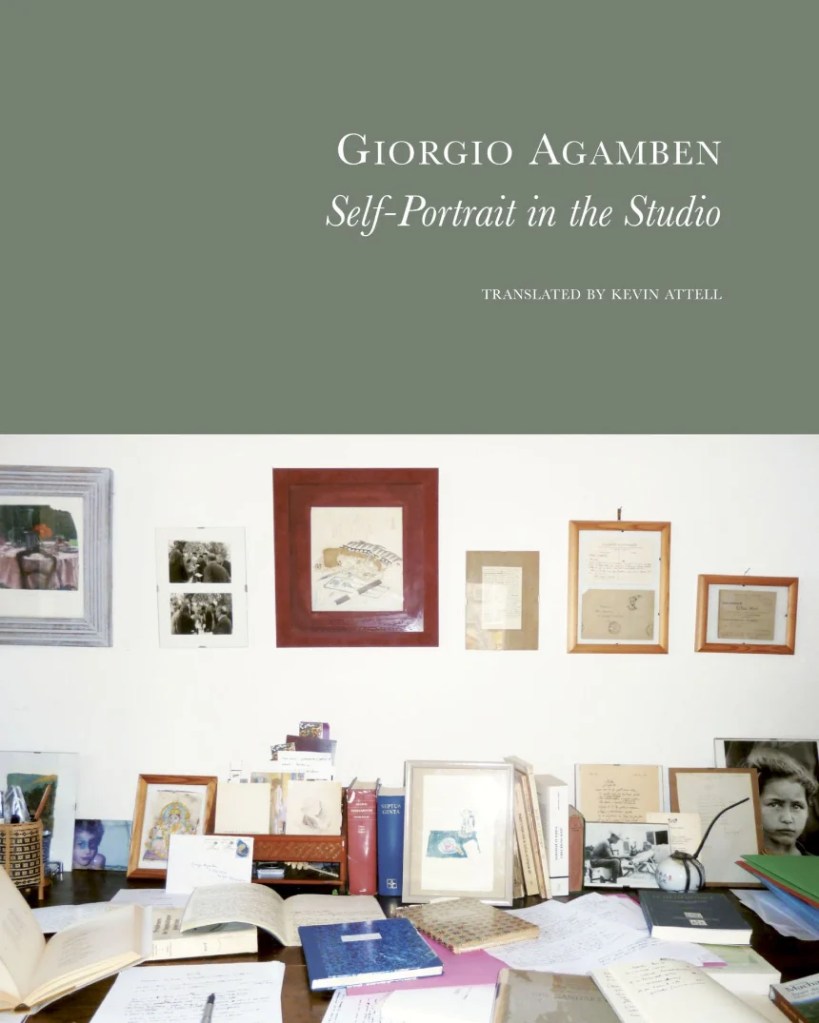

Granted that what Giorgio Agamben calls a “studio” might be better understood by English language readers as a “study,” the ideal space is the same: some kind of a desk , plenty of shelving for books, and some room on the walls for a few well-chosen prints or framed memorabilia. Over the years the Italian philosopher has occupied a number of studios, most rented or borrowed from friends, and each one, revisited through photographs often grainy or discoloured, contains the memories of friends and colleagues and others who have, through their writing, influenced and inspired him. With this slender, generously illustrated volume, Self-Portrait in the Studio, Agamben reflects on his own intellectual journey, which is, in his case, nothing less than a life journey, from the sixties through to the present day, via photographs, paintings, poems, beloved books, and precious friendships.

In this day of the ubiquitous selfie—that practice of intentionally placing oneself front and centre at any site of interest—one might expect a book with “self-portrait” (autoritratto) in the title to be a self-focused venture. Yet, although Agamben does appear with friends, mentors and fellow students in a number of the included photographs, his motivation is to centre those whose words and ideas have touched him and the lessons they have passed on. In a parenthetical aside he addresses this objective:

In this day of the ubiquitous selfie—that practice of intentionally placing oneself front and centre at any site of interest—one might expect a book with “self-portrait” (autoritratto) in the title to be a self-focused venture. Yet, although Agamben does appear with friends, mentors and fellow students in a number of the included photographs, his motivation is to centre those whose words and ideas have touched him and the lessons they have passed on. In a parenthetical aside he addresses this objective:

(What am I doing in this book? Am I not running the risk, as Ginevra [his spouse] says, of turning my studio into a museum through which I lead readers by the hand? Do I not remain too present, while I would have liked to disappear in the faces of friends and our meetings? To be sure, for me inhabiting meant to experience these friendships and meetings with the greatest possible intensity. But instead of inhabiting, is it not having that has got the upper hand? I believe I must run this risk. There is one thing, though, that I would like to make perfectly clear: that I am an epigone in the literal sense of the word, a being that is generated only out of others, and that never renounces this dependency, living in a continuous, happy epigenesis.)

This desire to stay out of his own way goes a long way to explaining the surprisingly engaging nature of this book. It is not a detailed or rigorous intellectual autobiography, but rather a chance to spend a little time with a philosopher who truly seems to delight in the exchange of ideas, someone who wishes to honour some of the friendships, writers and artists who have helped shape his own development over the years. Of course, given that he is writing from the vantage point of his early eighties, there is also a clear appreciation of the fact that the themes and dreams of a life are ever necessarily unfinished. In his preamble he muses: “While all our faculties seem to dimmish and fail us, the imagination grows to excess and takes up all possible space.” There are regrets—for example, sorrow that he did not come to appreciate Ingeborg Bachmann’s poetry while she was still alive—but the text ends with a positive, and still forward looking, affirmation of life and love.

Progress through this book of memories is essentially chronological, Agamben employs objects in or associations with his various studio settings as touchstones that trigger memories of a particular person or persons who came into his life, and, frequently, the poets or writers that any one connection might have him led to explore. The tapestry of a life of ideas ever expanding, moving from friendships with important contemporary literary and intellectual figures, to meditations on the ideas of those he came to know only through their work, and back again. He never devotes more than a few pages to any one individual, social group, or writer as he honours those who have influenced and inspired his own thought over time.

For myself, many of the individuals he talks about, including those he counts among his important friendships, were previously unknown to me (but easy to look up, of course), but others, especially the writers he feels a strong connection to—like Simone Weil, Walter Benjamin, Hölderlin, and Robert Walser—were not. Of particular interest is the way he considers our relationships to those we read carefully or enjoy close intellectual companionship—what is it to engage intensely with the ideas of others?

As he makes his way along this retrospective pathway, Agamben draws some striking connections that he measures himself against in assessing his own life. Notably, he comments on a piece written just three years before Walser’s commitment to the hospital where he would spend the rest of his life, in which he questions the idea that Hölderlin’s last decades were ones of misery, suggesting instead that his loss of his senses wisely afforded him the time and space to dream :

The tower in the carpenter’s house in Tübingen and the little hospital room in Herisau: these are two places on which we should never tire of meditating. What was accomplished within those walls—the refusal of reason on the part of two peerless poets—is the strongest objection that has ever been raised against our civilization. And once again, in the words of Simone Weil: only those who have accepted the most extreme state of social degradation can speak the truth.

I also believe that in the world that befell me, everything that seems desirable to me and seems worth living for can find a place only in a museum or a prison or a mental hospital. I know this with absolute certainty, but unlike Walser I have not had the courage to follow out all its consequences. In this sense, my relation to the facts of my existence that could not happen is just as—if not more—important than my relation to those that did. In our society, everything that is allowed to happen is of little interest, and an authentic autobiography should rather occupy itself with facts that did not.

So where does that put his little exercise in self-reflection? In a class of its own. With Self-Portrait in the Studio, Agamben, traces a rich network of interconnection, through personal contacts, study and research, and even, in some locations, a coincidental proximity to history, to produce a work that is entertaining, intelligent and humane.

Self-Portrait in the Studio by Giorgio Agamben is translated from the Italian by Kevin Attell and published by Seagull Books.