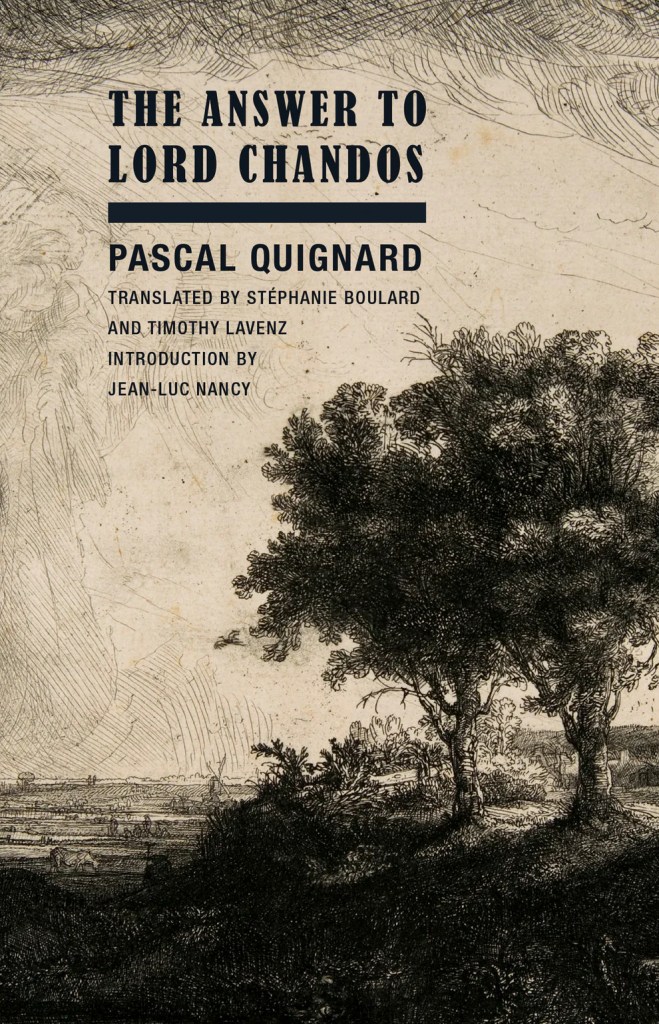

Austrian poet, writer and librettist, Hugo von Hofmannsthal signalled a break with his earlier works when, in 1902, he published the story “A Letter,” also known as “The Lord Chandos Letter.” It is presented as a letter to Francis Bacon, dated August 1604, from his (fictional) friend Philip, Lord Chandos, in which the latter defends his abandonment of the poetic life, and society in general, as a result of his nearly complete loss of the ability to express himself in words. The sentiment expressed in this communication echoes an abrupt change in Hofmannsthal’s own approach to language and the limits of the word so closely that it has been thought to have had at least some autobiographical grounding. But, it is, in fact reflective of the contemporary emergence of new ideas about thought and expression, especially in Vienna, and the impact that would have on philosophy, science and the arts. Although the exact context has been debated, clearly Hofmannsthal was seeking to express some aspects of his own shifting literary perspective through the existential crisis of faith in language expressed by his character in his fictional letter.

More than a century later, French author Pascal Quinard is not content to leave this influential “letter” as a one-sided communication. So he has picked up the pen of Lord Bacon to respond to Chandos (and presumably his creator) with The Answer to Lord Chandos. In his introduction, Jean-Luc Nancy suggests Quinard may have a wider perspective in mind:

More than a century later, French author Pascal Quinard is not content to leave this influential “letter” as a one-sided communication. So he has picked up the pen of Lord Bacon to respond to Chandos (and presumably his creator) with The Answer to Lord Chandos. In his introduction, Jean-Luc Nancy suggests Quinard may have a wider perspective in mind:

Literature began to distrust itself at the dawn of the twentieth century, beginning with Nietzsche and Mauthner (much read by Hofmannsthal). At the beginning of the twenty-first century, we doubt instead if literature still takes place. Hofmannsthal’s recoil before words responds to the wear and tear of a certain grandiloquence and literary profusion of the nineteenth century. The vibrant defense of those same words, in Quinard, responds to a banalization and informanization of language ushered in by the twentieth century.

The result is a moving defense of the vital importance of language and poetry that arises from decades of Quinard’s personal contemplation of the original story.

He opens this essay with an imaginative consideration of two artists who preferred to pull themselves away from the world, more comfortable with limited contact with others, but who continued to have faith in their art. He writes about how Emily Bronte’s time in Brussels in 1842, and the necessary social engagement required of her there, only deepened her need for solitude. Her beloved moorlands, which she wandered with her dog and pet bird of prey, served as her inspirational wellspring. Society was not essential for Bronte or for German-born English composer, George Handel. In 1710, Handel travelled to London where he would remain for the rest of his life, becoming in 1718, the director of music to the current duke of Chandos (hmm…) before becoming involved in opera and theatre. But as Quinard describes him, he preferred to live and compose in relative isolation:

Inside Handel’s small living room—according to the inventory made after his death—there was a large secretary made of walnut, a water bowl, a full-length mirror ringed with brass, and two striking wooden heads on which his wigs were placed. Two big heads without eyes or mouth, so that the wigs, reeking with sweat and smoke, could dry out when the evenings were over. So that the smell of society and its solicitations, its judgments, its resentments, its heartbreaks, were not brought any further into the house.

Ultimately, Quinard’s thoughts turn to “A Letter” and its author. Acknowledging that Hofmanthal had suffered a nervous breakdown right as the century turned, fueled by personal matters, Quinard, himself falling under the darkness of depression in 1978, fashioned a response to his fictional young letter writer.

Lord Chandos’ letter to Lord Bacon begins with an apology for taking two years responding to his friend’s last missive inquiring about his well-being. He then goes on to express his conviction that the inspired poet he once was is no more, and explain how he has lost his faith in language and the ability to express himself in any meaningful way. At the age of twenty-six he has abandoned a promising literary career and intends to retreat further from the society in which he was previously engaged. Quinard’s Lord Bacon opens his own answer to Lord Chandos with a similar apology for taking yet another two years to reply. But his explanation is initially simple—he strongly disagrees with his friend’s argument and has needed time to formulate an answer.

The response is relatively long and passionate, likely longer than the story that inspired it. But it serves as a moving defense of the power of poetry. Bacon’s argument carries an intensity that is sensual, pointed, and persistent. He is intent on chastising and encouraging his friend to pull him out of the abyss into which he has let himself fall and advise him to hold fast to his pen no matter what:

Remember that words only abandon those who have hollowed them out and somewhat devitalized them. And if words resist those who are in the middle of speaking: never do they resist those who write. Those who write have nothing but time for them, nothing but time to go back over their sentence, nothing but time to crack open their lexicons, their chronologies, their dictionaries, nothing but time to seek the help of their old, quite incomplete grammar manual which dates to the end of childhood, nothing but time to revisit, to revive, to re-etymologize, to revise to correct, to surprise. Do not resort to stupor.

Reading the original story before reading this treatise will enhance the experience of Quinard’s response, but it is not essential. This slight volume is a celebration of the expressive force and intrinsic value of literature that will speak to anyone who loves language.

The Answer to Lord Chandos by Pascal Quinard is translated from the French by Stéphanie Boulard and Timothy Lavenz, with an Introduction by Jean-Luc Nancy and published by Wakefield Press.