Grief and loss has its own language, one that cannot be forced, one that is found waiting when the mourner ready. That is the experience recounted in the 32nd addition to The Cahier Series, a collection of short meditations published by the Center for Writers & Translators at the American University of Paris in association with Sylph Editions. Each volume pairs an author and an illustrator or artist, and examines some aspect of the intersection of writing and translation, allowing a broad scope within which such ideas can be understood and explored. As such, each cahier opens a door to a different way of engaging the world.

James E. Montgomery’s Loss Sings is a deeply personal essay that owes its genesis to tragedy. On 24 August 2014, the distinguished Professor of Arabic’s seventeen-year-old son was struck by a car when walking with some friends in the city of Cambridge. He suffered what were described as “life-altering injuries.” The driver was uninsured. Suddenly his family’s world was forever altered as an entirely new set of realities, concerns, and anxieties came into play. The young man with a promising future now faced a life of serious physical disability, marked by increasing pain, decreased mobility, and the need for ongoing care. As surgery, rehabilitation, and the detailed record keeping required for legal purposes began to shape Montgomery’s life, he discovered an unexpected appreciation for a cycle of Arabic laments that had long left him unmoved and indifferent. In the early months after his son’s accident, a personal translation project involving these poems emerged. Three years later he recorded his reflections on his son’s injury and his thoughts on memory and the articulation of loss in a series of dated diary entries. Presented together with a selection of his newly translated verses, the present cahier was born.

James E. Montgomery’s Loss Sings is a deeply personal essay that owes its genesis to tragedy. On 24 August 2014, the distinguished Professor of Arabic’s seventeen-year-old son was struck by a car when walking with some friends in the city of Cambridge. He suffered what were described as “life-altering injuries.” The driver was uninsured. Suddenly his family’s world was forever altered as an entirely new set of realities, concerns, and anxieties came into play. The young man with a promising future now faced a life of serious physical disability, marked by increasing pain, decreased mobility, and the need for ongoing care. As surgery, rehabilitation, and the detailed record keeping required for legal purposes began to shape Montgomery’s life, he discovered an unexpected appreciation for a cycle of Arabic laments that had long left him unmoved and indifferent. In the early months after his son’s accident, a personal translation project involving these poems emerged. Three years later he recorded his reflections on his son’s injury and his thoughts on memory and the articulation of loss in a series of dated diary entries. Presented together with a selection of his newly translated verses, the present cahier was born.

The poems at the centre of this fascinating account, are the threnodies of the seventh-century Arabic poet Tumāḍir bint ‘Amr, known to posterity as al-Khansā, a woman who composed and sang hymns to the loss of her two brothers in battle—more than a hundred wailing odes that were memorized and passed on for two centuries before they were committed to writing. Although Montgomery had taught these well-known elegies for three decades, through significant losses and traumas of his own including a close proximity to the surreal horror of the attack on the World Trade Towers, he had found them repetitive and cliched. It took his son’s injury to unlock their power. As a parent with a seriously injured child, the rules of order were suddenly rewritten. He realized that his son’s need for assistance would increase as his own physical abilities declined, and when an unexpected potential health problem of his own arose, his concerns for the future intensified.

Memory is a strange place. It is unreliable, pliant, liable – mercifully so. It makes so many mistakes, gets so much wrong. An event like the one I am describing rips to shreds the veil of the commonplace and the mundane, and memory is charged with the task of remembering the future, of recalling the unusual; for such events reveal to us that the future is little more than a memory.

What unfolds over the course of less than forty pages is a multi-stranded meditation on grief, loss, and the relationship between trauma and memory. As Montgomery notes, the confusion that commonly strikes in the aftermath of trauma is a response to the confrontation of previously trusted memory with a “new reality, an unalterable experience.” He recognizes a close analogy in literary translation. In order for a translator to recreate a literary work in another language, decisions must be made about what can be left out as much as what one wishes to retain. With poetry in particular, he says, it may be the only means of transmitting what is irreducibly poetic, and as such, literary translation is “more akin to trauma than it is to memory.” As trauma leaves one at odds to make sense of the world, often bound to a silence that swallows up attempts to give voice to grief, the mourner is forced to navigate a “no-man’s land” between one remembered reality and a new one. Literary translation echoes this process, and through the act of translating al-Khansā’s poetry in particular, Montgomery is able to articulate his own experience of grief and loss through an understanding and appreciation of the very elements that once irked him in these classical Arabic laments.

We are all likely well aware of the kind of cliché, stock phrases, and time-worm comforts that are offered as a solace in times of loss. When faced with profound grief ourselves, there is often a sense that common statements fall short of the magnitude of our emotions. Yet we reach for them—in condolences, eulogies, obituaries. Or worse, for fear of sounding banal we say nothing. It takes the near loss of his son for Montgomery to finally feel the power of these clichés, in the personal and the poetic:

Experience, memory, artifice and art are confronted by the absence of comfort, and earlier versions of a poet’s selves are rehearsed and re-inscribed in memory – but the brute truth of the mundanity of death is the age-old cliché about clichés, namely that, like death, they are too true.

The seventh-century warrior society to which al-Khansā belonged was bound by intense devotion to the cult of the ancestor. Death in battle demanded both vengeance and epic memorial. The latter was the responsibility of women, and her sequence of Arabic keenings—songs of loss— are the most extensive, powerful and poetically inventive to have survived to the present. Her poems are defiant. She will allow no accommodation of her loss over time, her grief stands still, “(h)er doleful, disembodied voice, entombed forever in the inanimate sarcophagus of metre, rhyme, and language.”

Night is long, denies sleep.

. I am crippled

by the news—

. Ibn ‘Amr is dead.

I will cry my shock.

. Why shouldn’t I?

Time is fickle,

. Disaster shock.

Eyes, weep

. for my dear brother!

Today, the world

. feels my pain.

Montgomery’s reflections on his own experiences with loss and the parallels he sees in translation speak clearly to lived grief and trauma. The yearning, aching threnodies of al-Khansā woven throughout, call from the distant past with a pain and longing that is recognizable, real, especially for anyone who is, as I am, still caught in the lingering aftermath of a series of significant losses. But throughout my engagement with this book there was one thought that I could not shake, a possible understanding that the author himself is perhaps not fully aware of. He admits that he is not entirely certain why these ancient Arabic laments finally reached into him when they did.

I worked for years with the survivors of acquired brain injury and their families. I recall one family in particular whose son was injured in a single vehicle rollover in his late teens. His parents admitted at the intake, to a double sense of grief—for their son’s ever-altered future, and for their loss of an image of their own anticipated freedom on the cusp of their youngest child’s pending adult independence. Two futures and their attendant memories altered in an instant. Yet this kind of grief—the grief of survival—is not easily mediated. When the parents attempted to attend a grief support group in their community they were pushed away. “What do you have to grieve?” they were asked, “You still have your son.” There is no accepted ritual or memorial for this kind of loss. With each step through rehabilitation, fighting for funding, worrying about an undefined but infinitely more precarious future, a song of loss sung anew every day. It does not surprise me in the least that a sequence of laments that hold so fast to grief, repeating, reinforcing and seeking voice in the comfort of cliché would break through at this time in Montgomery’s life.

How fortunate that he was able to hear them and feel inclined to guide these verses across the distances of language and time to share with us. Paired with abstract illustrations in black and shades of grey by artist Alison Watt, this small volume speaks to the universality of loss and the longing to find expression through the stories, myths and poems we turn to in times of trauma.

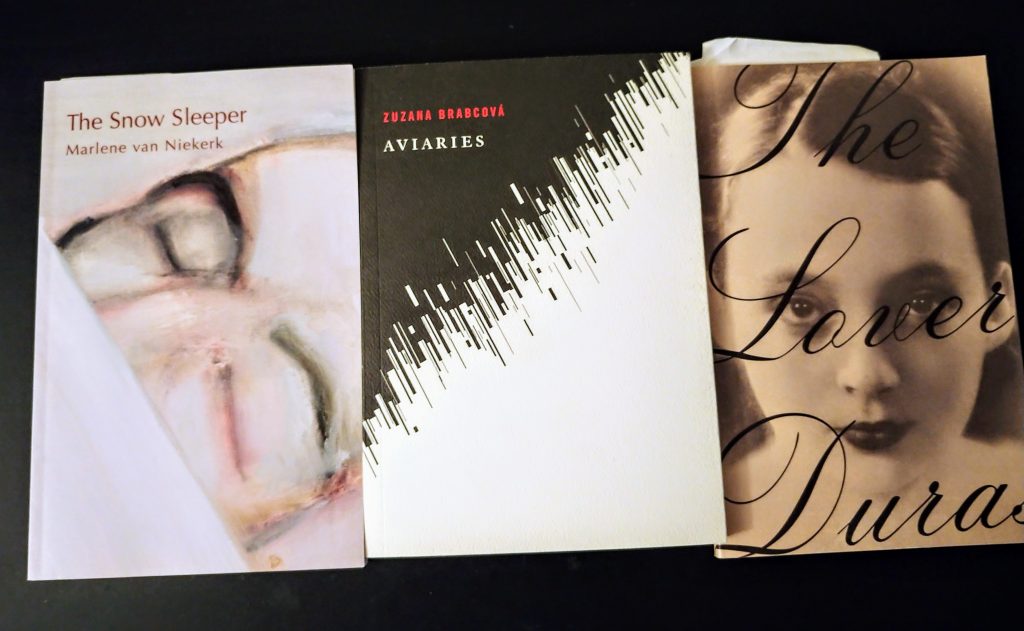

Over the past couple of years I have, often in defiance, insisted on writing about the poetry I read. At the same time, my focus in reading poetry has shifted, taking in more contemporary poets, as well as experimental and translated works. But I know nothing about formal analysis, and even less about how one might set out to write a poem. But I’ve not let that stop me from attempting the odd poetic effort, even if I always feel like I’m writing into the dark. Stumbling into it sideways.

Over the past couple of years I have, often in defiance, insisted on writing about the poetry I read. At the same time, my focus in reading poetry has shifted, taking in more contemporary poets, as well as experimental and translated works. But I know nothing about formal analysis, and even less about how one might set out to write a poem. But I’ve not let that stop me from attempting the odd poetic effort, even if I always feel like I’m writing into the dark. Stumbling into it sideways.