“Windows, even those with heavy shutters, were no help against the rain. It came with a wild westerly one moment and with a sirocco the next, constantly changed the angle at which it fell, attacking now frontally, now from the side, until it had crept through every invisible opening in the walls and woodwork. In their rooms, people made barriers of towels and babies’ nappies beneath the windows. When they were sodden they would be wrung out in the bathroom and quickly returned to the improvised dykes.

Roofs let through water like a poorly controlled national border. Like in a bizarre game of chess, families pulled out pots and pans across the floor: Casserole to f3, frying pan to d2.”

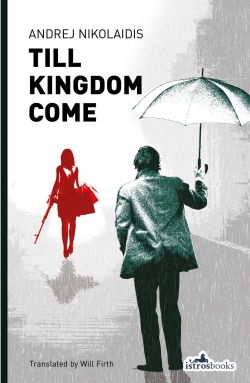

As befits its title, Till Kingdom Come – the latest novel by Montenegrin author Andrej Nikolaidis’, his third to be released in English by London based indie publisher Istros Books – opens with a deluge of Biblical proportions. The heavens above the historically rich tourist town of Ulcinj have unleashed an extended season of torrential and relentless rain. As water rushes down the streets and seeps through walls and floorboards, the reader is quickly introduced to the narrator, a freelance journalist, a man who faces the world with reserved and stoic humour. Or so it seems. But then nothing is what it seems, and for our poor narrator most of all.

As befits its title, Till Kingdom Come – the latest novel by Montenegrin author Andrej Nikolaidis’, his third to be released in English by London based indie publisher Istros Books – opens with a deluge of Biblical proportions. The heavens above the historically rich tourist town of Ulcinj have unleashed an extended season of torrential and relentless rain. As water rushes down the streets and seeps through walls and floorboards, the reader is quickly introduced to the narrator, a freelance journalist, a man who faces the world with reserved and stoic humour. Or so it seems. But then nothing is what it seems, and for our poor narrator most of all.

It soon becomes apparent that our hero has long suffered from periodic lapses in temporal/spatial reality. He has been known to just drift off, seeming to have lost consciousness to those around him, while he finds himself in some distant country or city previously strange to him that he suddenly knows intimately, until he wakes up back where he started. This dissociative tendency which has haunted him for years has left him with a rather slippery sense of self that, more than anything, seems to engender an abiding sense of ambivalence. That is, until the arrival of a man claiming to be his uncle causes him to have reason to doubt the veracity of his entire existence. He had believed that his mother was dead and he was raised by his grandmother, a belief supported with stories, photographs, a history and an unusual Jewish name. Discovering that his past was faked, sets him off on a passionate journey of speculation and self discovery, assistsed by a police inspector, directed by an anonymous email source and fueled by an obsessive fascination with serial killers and conspiracy theories.

Biting in intensity, taking broad political and historical swipes at medieval and modern history – poking the bones of Oliver Cromwell and stirring up the horrors of the Balkan War – Nikolaidis is in fine form, building upon and expanding the canvases he painted in his previously translated works, The Coming and The Son. Ah yes, Thomas Bernhard would be proud. Yet, for its sarcastic humour, metafictional wanderings through Red Lion Square in London and up the stairs of Conway Hall to the tiny second story office of Istros Books, and the endless speculations about the role of the black arts in the exceptional acts of cruelty and violence perpetrated by mankind that have littered history; Till Kingdom Come is a starkly serious book. The narrator exists on a plane of his own, while his friends succumb to pressure of feeling too much, of being unable to cope with a world that is fundamentally uncaring. As he muses at one point:

“Alas, there is only one happy ending – the Apocalypse – even if it is only a promise. Everything else is just an open ending, a continuous series of open endings, whose resolution not only resolves nothing but further complicates already unbearably complicated things.”

For my money, Till Kingdom Come is a more mature and demanding work than The Coming and The Son, both of which I thoroughly enjoyed. Nikolaidis is a highly political journalist and here he is clearly intent to skewer politics and economics with more direct, at times shocking, barbs. The Bernhard inspired intensity of The Son is dialed back a little while the historical diversions that provided an intriguing counter commentary to The Coming have been worked back into the narrative. As in these first two Istros releases, translator Will Firth captures the mood and intensity seamlessly. And, on an entirely personal note, it was a delight to see Red Lion Square and the Istros Books office worked into the text. However when I visited this summer I did not magically find myself strolling down Oxford Street. I got hopelessly lost and had to be rescued from the Tube Station by the editor herself, but then London on a map and London on the ground for someone who has never been there is, well, a metaphysical rather than metafictional experience to say the least!

Copyright JM Schreiber 2015