“In my dream, I am the president,

When I awake, I am the beggar of the world.”

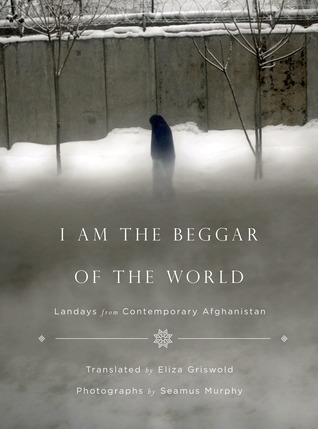

With a long history, passed down through generations, landays are traditional two line poems recited or sung by the mostly illiterate Pashtun people who live along the border region between Pakistan and Afghanistan. They are composed of twenty-two syllables – nine in the first line and thirteen in the second. For the women in this area who face social and cultural restraints that define and restrict their lives, these anonymous couplets have become an important medium for self expression. Sometimes they gather to share or perform the landays they have learned, updated or re-invented; but radio and the ubiquitous social media and cell phones have also been worked into a new modern network for sharing.

I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan, a collaboration between translator and poet Eliza Griswold and photographer Seamus Murphy, is a sensitive and moving collection of landays, brief essays, and photographs. Upon hearing of the death of a teenaged poet who had been forbidden by her family to write poems and burned herself in protest, Griswold was inspired to journey to Afghanistan to explore the role of landays in the lives of Pashtun women. She returned to collect some of these poems, assisted by native speakers and a Pashta translator, Asma Safi, who sadly died of a heart condition before the project was complete. Arranging meetings as an American was not always easy – being under occupation is a difficult, deadly environment – but along the way she collected the words and stories of some very strong, fascinating women.

I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan, a collaboration between translator and poet Eliza Griswold and photographer Seamus Murphy, is a sensitive and moving collection of landays, brief essays, and photographs. Upon hearing of the death of a teenaged poet who had been forbidden by her family to write poems and burned herself in protest, Griswold was inspired to journey to Afghanistan to explore the role of landays in the lives of Pashtun women. She returned to collect some of these poems, assisted by native speakers and a Pashta translator, Asma Safi, who sadly died of a heart condition before the project was complete. Arranging meetings as an American was not always easy – being under occupation is a difficult, deadly environment – but along the way she collected the words and stories of some very strong, fascinating women.

Divided into three sections, the first is dedicated to Love. Many of the couplets are brazenly racy, teasing and modern. Yet because landays are by their nature anonymous, no woman can be held responsible for sharing them or for the contemporary imagery has been worked into the more traditional versions:

“Embrace me in your suicide vest

but don’t say I won’t give you a kiss.”“Your eyes aren’t eyes. They’re bees.

I can find no cure for their sting.”“”How much simpler can love be?

Let’s get engaged. Text me.”

The second section is dedictated to the themes of Grief and Separation. Suffering and servitude are enduring features of the lives of Pashtun women. Marriage implies both. Curiously love also features throughout the poems in this section because romantic love is forbidden. If a young woman is discovered to be in love with a man she can be killed or driven to take her own life to preserve her family’s honour.

“Our secret love has been discovered.

You run one way and I’ll flee the other.”

Once married, having one’s husband take another wife is emotionally painful, but being passed over altogether or married off to an old man can be worse.

“Listen, friends, and share my despair

My cruel father is selling me to an old goat.”

The final section explores War and Homeland. Complex, mixed emotions, anger and sorrow rise up here in poems that are moving and, again, shockingly modern. A long legacy of occupation under British, Russian, and American forces has placed the women of Afghanistan in a difficult position, torn between the brutality of American protection and the combined threat and promise of the Taliban. The landays and the images in this section are especially powerful and represent sentiments that women would not be able to express so readily in any other forum:

“Be black with gunpowder or bloodred

but don’t come home whole and disgrace my bed.”“Beneath her scarf, her honor was pure.

Now she flees Kabul bareheaded and poor.”“May God destroy your tank and your drone,

you who’ve destroyed my village, my home.”

This slim volume is a testament to the resilience of the Pashtun women in the face of the violence, threats and restraints they live with every day. These traditional two-line poems provide a framework for illiterate women to express themselves and share their sorrows, joys and wisdom with their sisters. In Afghanistan they still face risks in committing their own poetry to paper when they are able, so this oral tradition remains important, even if modern devices like cell phones have expanded their network. This beautiful book which pairs the simple landays with muted black and white photographs documenting the people of Afghanistan, the sparse landscape and the violence of war, provides a rare opportunity to hear the intimate voices of women that might otherwise be silenced.