I came rather late to the work of Pakistani British author Aamer Hussein, surreptitiously as I’ve said before, through an unsolicited essay I received when I was an editor for an online journal, from a writer who had also encountered him by chance when she found a copy of his collection Insomnia in a “decaying” bookstore. The essay impressed me so much that before I sent a letter of acceptance I had already ordered a copy of Insomnia for myself. This was, I knew, an author I needed to read:

Hussein’s stories display an audacious ability to synthesize complexities of social subjectivity; yet behind this complex surface lies a rich silence. His stories remain porous, marked by gaps and holes—a kind of silence which, rather than a lack, represents a positive capacity, Hussein’s most potent mode. What Aamer Hussein offers us is an invaluable model of resistance in literature: resistance that works through silence, through that which remains unsaid.[1]

Yet, if silence can be such an effective mechanism in a fictional context, would the same author approach autobiographical writing with greater detail or, dare we say, denseness? Not if you’re Aamer Hussein.

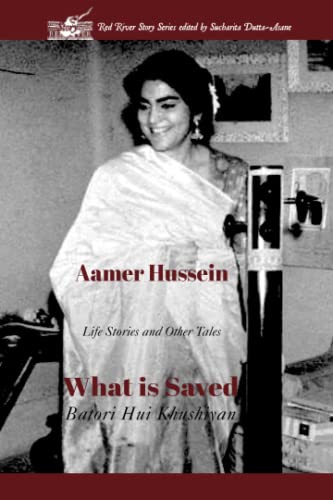

What is Saved, released earlier this year as part of the Red River Story Series, is a selection of “Life Stories and Other Tales” gathered, editor Sucharita Dutta-Asane tells us, from two earlier collections, Hermitage and Restless: Instead of an Autobiography. Among these short works are accounts drawn from Hussein’s childhood in Karachi, tales inspired by friends and family members, a variety of true and re-imagined truths set in London where he has lived since the age of fifteen and at various points in his long process of rebuilding his connection to the country of his birth. If the pieces gathered in What is Saved might in some sense speak, as the Urdu subtitle—Batori Hui Khushiyan—implies, to all happiness, anyone familiar with Hussein’s fiction knows that in his work happiness tends to be tinged with melancholy. In this collection, which deals so openly with longing, displacement, illness and mortality, a similar wistfulness again permeates the quiet hopefulness that buoys his prose.

What is Saved, released earlier this year as part of the Red River Story Series, is a selection of “Life Stories and Other Tales” gathered, editor Sucharita Dutta-Asane tells us, from two earlier collections, Hermitage and Restless: Instead of an Autobiography. Among these short works are accounts drawn from Hussein’s childhood in Karachi, tales inspired by friends and family members, a variety of true and re-imagined truths set in London where he has lived since the age of fifteen and at various points in his long process of rebuilding his connection to the country of his birth. If the pieces gathered in What is Saved might in some sense speak, as the Urdu subtitle—Batori Hui Khushiyan—implies, to all happiness, anyone familiar with Hussein’s fiction knows that in his work happiness tends to be tinged with melancholy. In this collection, which deals so openly with longing, displacement, illness and mortality, a similar wistfulness again permeates the quiet hopefulness that buoys his prose.

Loosely, the early autobiographical and autofictional pieces highlight Hussein’s early years in Karachi, offering a portrait of the culture of the city in the 1960s. His life is enriched by his mother’s love of music, and a proximity to Urdu literary figures and even a film star who moves into his neighbourhood. These are followed by a selection of stories and fable-like pieces, some no more than a page in length, inspired by friends or family members or traditional tales. But the themes that become prominent through the balance of the collection include literary friendships, the Covid-19 lockdowns, the loss of loved ones, injury and, finally, life with a terminal cancer diagnosis. Whether he is reflecting on life’s rewards and realities directly or through the lens of fiction, birds, gardens, and flowers tend to create a greater sense of continuity than any particular place or time. He is ever a writer who captures the ambiguity of belonging—in a city, in a culture, or in relationship to others.

Two of my favourite pieces in What is Saved fall onto the memoir side of the fiction/nonfiction equation and address elements of the connection between language and identity. In the first, “Teacher,” the only essay in this volume originally composed in Urdu (translated by Shahbano Alvi), Hussein recalls a man he called Shah sahab, the London based friend of his parents whose private tutelage helped him gain confidence in his mother tongue. With his tutor’s support, the teenaged Hussein was finally able to read, in the original Urdu, a book he’d first encountered in English translation, a text that had already had a profound impact on his understanding of the world he came from:

My eyes opened to the imagery of an intriguing past; the imposition of the British Raj in the 19th century and the downfall of the Oudh culture of which I’d been only vaguely aware. Brought up in the Westernised circles of Karachi, I had been exposed for the most part to history books written by the Western historians.

Thus, halfway across the world from his homeland, he would become sufficiently proficient to study Urdu prose and poetry at university even if he would go on to dedicate himself to English literature, as a teacher and writer. In a later piece, he talks about returning to Urdu, as he begins to spend more time in Pakistan and learns to trust his ability to creatively express himself in the language.

The second essay, “Suyin: A Friendship,” remembers a teacher of a different kind—a literary mentor. Although her books are now out of print, I remember when Han Suyin’s novels were a popular item in the bookstores I worked at during my university years but I had no idea what had happened to her. In this piece, Hussein reflects on his friendship with the Chinese born author and doctor, nearly forty years his senior, who encouraged him to listen to the music of Urdu, a language she loved without understanding it. Her advice was wise. “Trapped between tongues like her, I did what she couldn’t,” he says, “I reclaimed another self in my forgotten tongue.” In thinking back on their profound and yet ultimately strained relationship—she influenced his career even if she could not remain the writer he wanted her to be—his own journey away from and back to both Pakistan and Urdu is mapped out. It was not a path without its own inherent contradictions, especially at the beginning:

Reclaiming Pakistan had made my fragile anchor slip away and my feet were sliding on slippery sand. My terms of belonging had changed: I was not whole. I wasn’t a Westerner of foreign origin. I was not someone who, to quote Suyin, happened to live abroad and went back for my roots: I was someone who had left behind a homeland and never found anything to replace the empty patch.

There is a restless running through many of the pieces in this collection that echoes Hussein’s movement back and forth between language and place. It finds him, or his fictional alter egos, feeling isolated and confined by the restrictions that a broken leg, pandemic lockdowns or the medical implications of disease impose, but remaining resistant and unwilling to fall into complacency. Between the lines, a vulnerability exists, as it does for any one of us, but Hussein has a way of writing, especially in the memoir/personal essay form, that carries his reader just to edge, revealing only what is needed, more concerned with what is felt and leaving silence to hold what cannot be answered.

What is Saved: Batori Hui Khushiyan (Life Stories and Other Tales) by Aamer Hussein is published by Red River Story.

[1] Ali Raz, “Silence as Resistence in Aamer Hussein’s Stories,” 3:AM Magazine, Published May 15, 2018. https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/silence-as-resistance-in-aamer-husseins-stories/