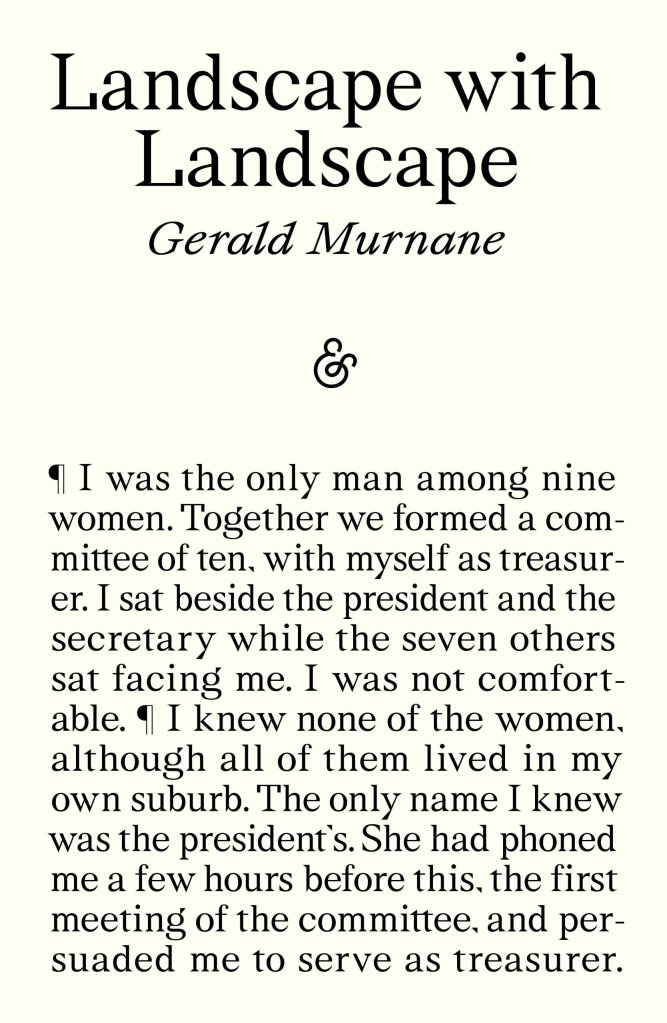

In his Foreword to Landscape with Landscape, written for its 2016 re-issue with Giramondo, Gerald Murnane describes his reaction to a number negative reviews that this, his fourth work and first foray into short fiction, received upon its release. He admits that he ultimately felt vindicated when others confessed to liking it and it achieved some modest rewards, but as he puts it: “here it is being republished thirty years after its harsh early life and when it’s old enough to stand up for itself.” Well, now it is seeing its first release outside of Australia, and it’s yet another decade older and its author has finally been properly “discovered” at home and abroad. So, does it stand up well? That depends, perhaps, on just how much of the classic Murnane narrator one can take, because this collection of six loosely interlinked stories (or novellas—most of the pieces is about 50 pages long) and, with the exception of one especially clever, and somewhat unsettling, tale, it could be argued that the length of the individual stories tends to undermine their impact, individually, and of the project as a whole. However, many readers may well feel differently.

Landscape with Landscape was first published in 1985, three years after The Plains, his elusive and evocative tale of an aspiring filmmaker who ventures into a vast, open landscape with plans to make a film that, decades on, have yet to come to fruition. Meanwhile, the stories in Landscape are firmly rooted in a suburban Melbourne of the 1960s and 70s and its outlying districts, even if that “Melbourne” is, one case, bizarrely transplanted and turned upside down in distant Paraguay. But Murnane’s unnamed narrators are all obsessed with a landscape of some kind, even if it exists solely within their imaginations. They all dream of becoming writers or poets, sometimes with a role model, like Kerouac or Housman, and typically they toil away in unpublished isolation (even if they marry and have a family), work as civil servants or teachers, and drink heavily. There is often a legacy of Catholic guilt, sexual frustration, and social awkwardness, and each of these variations on the Murnane-type narrator is characterized by a self-obsessed, myopic, almost solipsistic nature that, at times, even he seems to acknowledge. Finally, in each story the narrator mentions a story he is reading or that he has just finished, or published, after decades of false starts, and the title of that work is the title of the story that follows.

Landscape with Landscape was first published in 1985, three years after The Plains, his elusive and evocative tale of an aspiring filmmaker who ventures into a vast, open landscape with plans to make a film that, decades on, have yet to come to fruition. Meanwhile, the stories in Landscape are firmly rooted in a suburban Melbourne of the 1960s and 70s and its outlying districts, even if that “Melbourne” is, one case, bizarrely transplanted and turned upside down in distant Paraguay. But Murnane’s unnamed narrators are all obsessed with a landscape of some kind, even if it exists solely within their imaginations. They all dream of becoming writers or poets, sometimes with a role model, like Kerouac or Housman, and typically they toil away in unpublished isolation (even if they marry and have a family), work as civil servants or teachers, and drink heavily. There is often a legacy of Catholic guilt, sexual frustration, and social awkwardness, and each of these variations on the Murnane-type narrator is characterized by a self-obsessed, myopic, almost solipsistic nature that, at times, even he seems to acknowledge. Finally, in each story the narrator mentions a story he is reading or that he has just finished, or published, after decades of false starts, and the title of that work is the title of the story that follows.

Taken together, the stories in this collection explore the slow simmer of literary ambition and the way it not only motivates the protagonist, but serves to keep him isolated from those around him. Everything is filtered through the narrator’s imagination, there is no dialogue and few characters are actually given names—most are referred to with a measured anonymity like “my wife,” “the president,” “my younger cousin,” “the Artist.” This social disconnect creates a narrative that centres the protagonist’s obsessions and idiosyncrasies, but as some of these stories drag out over several unproductive or counterproductive decades they risk losing their steam even if there are some really wonderful elements at play. Just how many times can a man wake up with a hangover and vague memories of vomiting in a bush in pursuit of a concept of a landscape he can’t even articulate before he outstays his welcome?

Having said all this, there is something to like in each of the stories in Landscape with Landscape and whether it works better as whole or a collection—even Murnane admits he was not entirely certain what it was as he put it together—is best judged by the reader. But one can argue that the centrepiece of the work is the third story, “The Battle of Acosta Nu.” In the late 1800s, a small group of Australians migrated to Paraguay to establish a utopian socialist colony. Due to internal conflict and difficult living conditions, most of the original settlers returned home, but a number of families stayed, eventually marrying into the local population and their descendants remain there to this day. Here Murnane’s narrator, an even more proud and dysfunctional protagonist than usual, is a man whose father made him aware of his superior Australian heritage which he believes sets him apart from the primitive Paraguayans around him. He does not speak of his background—though he suspects others sense his difference—and learns whatever he can about Australia so he can one day return to his native land. In his mind he superimposes an Australianness on his environment (he lives in Melbourne), while shunning Paraguayan culture and civilization (which is, of course, perfectly modern). Despairing of ever finding a true Australian woman, however, he is forced to marry a local, and accepts that his firstborn, a daughter, is necessarily Paraguayan, but when his son arrives he feels obligated to help the boy understand that he too is set apart from others. Yet, when his son becomes critically ill, things really start to become disturbing.

The doctors talked quietly with their backs to me. I saw how absurd had been my thinking on the way to the hospital that some young doctor might take me aside when he met me and ask me if I could explain some oddity he had found in my son: perhaps an unheard-of blood-group or an unusually well-developed heart or merely the boy’s astonishing toughness in his fight against this infection. (I had thought at the time that I would tell the doctor the truth about my son and myself – not as a boast but simply to remind the medical man that his science overlooked much of importance: that if he wanted to know what enabled people to survive he had better ask himself what was the very essence of a man and what distinguished one race of men from another and why years of exile could inure a body against lesser hardships.) But of course the doctors had nothing to ask me.

The narrator, so convinced of his—and his son’s—superiority, is unable to acknowledge the gravity of his situation to the extent that he is even divorced from his body’s natural emotional responses. He is determined to keep trying to rise above what is going on. This story is absurd, at first funny and then not funny at all. It raises countless questions about identity and sanity, and what it means to find one’s place in the world. Somehow, the landscape that is always just out of reach is the one you are longing for. It is also the one you are least likely to recognize even if it is stretched out before you.

Landscape with Landscape by Gerald Murnane is published by And Other Stories (and in Australia by Giramondo).