these are the chronicles of my village, the vessels of remembering and reminiscing, tale upon tale of yesterday, yesteryear, yestercentury or yestermillennia, now plainly precise, now hazily adrift, an abundance, or maybe an overabundance of news that reads like some kind of a novel, some kind of novella or some kind of essay reshaped into fictional form, they, the news, the chronicles, constantly expand, contract, compel, pressure, evoke and awaken before culminating in a perhaps inevitable explosion, shattering all the burnished grandiose narratives that so desperately try to conceal the fatal historical disabilities of a land.

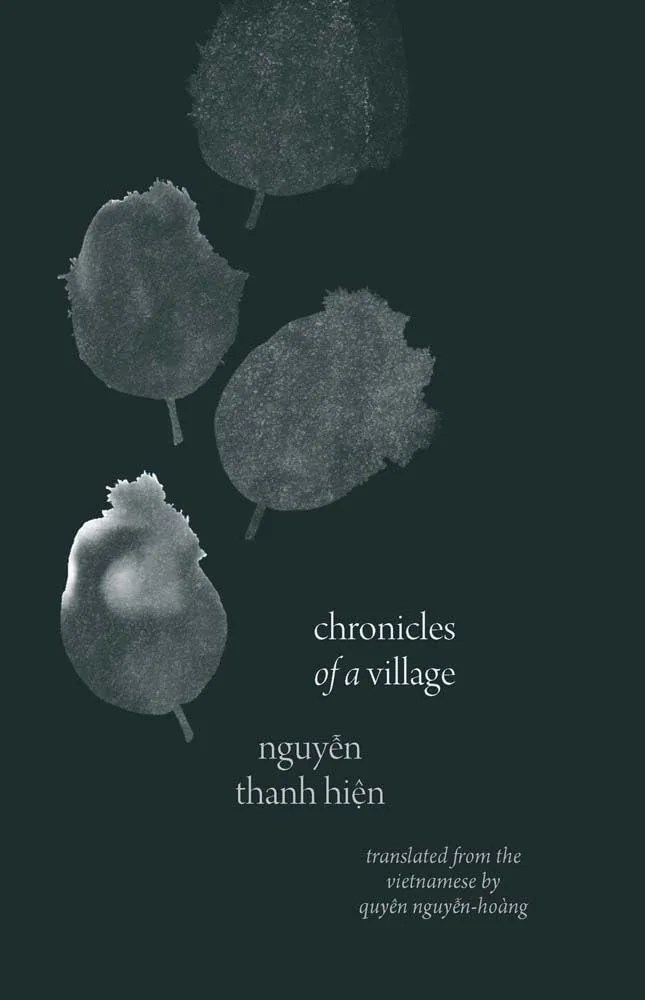

In a small village, nestled at the foot of Mun Mountain, somewhere in Central Vietnam, a scribe is recording a history—of his life, his family, his village, his community. Mythical visitors, birds and beasts, dynastical rulers, colonizers, invaders, and ghosts pass in and out of his amorphous, fragmented, non-chronological account. But binding it together are memories, of childhood and family, and of the routines of agricultural life. Nguyễn Thanh Hiện’s lyrical Chronicles of a Village cannot easily be categorized. Is it a collection of stories, a novella, a documentary or a prose poem? Labels do not matter. It is a mesmerizing evocation of the passage of time—a record of what is lost, what is gained, and what remains—a shifting portrait of a land and its people.

Chronicles opens with an account of the disruptive arrival of “sightless humans” marching into the village. No one is quite prepared for the danger these outsiders represent. They march the residents out into the open and when the narrator’s father dares to address the invaders, he is tied up and taken away. This narrative is followed by a detailed note further explaining the nature of the man who has been captured and who will, in time, be freed. At this point this work appears to be presenting itself a historical document of some kind, which it is in its way, but what unfolds in the ensuing pages refuses to follow conventions a western reader might anticipate, the story to be told exists on many levels at once. Even the scribe himself is unable to clearly define his project, as in the quote above and at many other points where he approaches the question of fictions and truths, histories and unhistories.

Chronicles opens with an account of the disruptive arrival of “sightless humans” marching into the village. No one is quite prepared for the danger these outsiders represent. They march the residents out into the open and when the narrator’s father dares to address the invaders, he is tied up and taken away. This narrative is followed by a detailed note further explaining the nature of the man who has been captured and who will, in time, be freed. At this point this work appears to be presenting itself a historical document of some kind, which it is in its way, but what unfolds in the ensuing pages refuses to follow conventions a western reader might anticipate, the story to be told exists on many levels at once. Even the scribe himself is unable to clearly define his project, as in the quote above and at many other points where he approaches the question of fictions and truths, histories and unhistories.

The mythic and magic of Mun Mountain rises above the quotidian routine defined by rice and fabric. The cultivation of fields and the weaving of cotton have supported this small community for centuries, skills originally brought to them by god-like travellers who arrived in the Land of the Upper Forest—or so the legend goes—taught to the people, and passed down from father to son and mother to daughter. The scribe, using the lowercase “i” as first person pronoun, favours commas over full stops to affect a living, breathing quality to the tales he shares. In long, unbroken sentences that that often extend for pages, he writes of his childhood, his parents and older brother, and other important characters of his hometown, of his “birthsoil.” He writes of the forest, the birds, and the mystical creatures that could be imagined in the formations atop the mountain. And, of course, along with stories of the rising and falling political dynasties of the distant past, he recounts the ways the outside world began to impose control, first over his nation and eventually his local region in more recent times.

At first, he recalls, war in his country caused by the French colonists seemed so far away. To adolescent boys it seemed romantic, their heads filled with images of troops fighting on horseback as in the wars they had learned about in school. It seemed romantic, like a fairy tale and they set about secretly weaving grass into horses. But when adult war suddenly arrived, with fire bombings and destruction, the magic was incinerated as were many homes and villages. The lives of classmates, friends and first girlfriends, were lost.

the sound was abrupt yet belonged to an eternity, and afterwards, young maiden, you didn’t come around here anymore, at nightfall, the night herons no longer cried among the dews, my fellow villagers went their separate ways, in two distinct directions along the horizon, to tell the truth no one wanted that to happen, somebody said it was because a venomous wind blew past and entangled everyone’s way of thinking, it was true that my homeland was then tumbling into the sorrowing pages of history

The chronicles, as they unfold, weave together fragmentary, often dreamlike stories that seem, at first glance, to be unconnected. However, each chapter is linked to the next through images and ideas—that which closes one is picked up and carried, perhaps in a new direction, in the next. Motifs and phrases repeat, within chapters and across the work as a whole, imbuing the prose with an incantatory rhythm and meditative feel. It honours the past, acknowledges the devastation of war, and offers the hope of continuity, of resilience:

i’d like to speak of the tokay geckos that lived in the hollows of the sandbox trees by the village entrance as if i were delivering , on behalf of my fellow villagers, a note of gratitude to the descendants of the beastly dinosaurs, those creatures that existed back in the Triassic days of the Mesozoic Era, if those geckos living in the hollows of the sandbox trees by the village entrance were the legitimate descendants of those dinosaurs, evolution might stand a chance of brightening up, for centuries the gecko families had been living in the hollows of those sandbox trees by the village entrance, but once the war began, the trees were all knocked down by bombs and bullets, there was not a single plant left by the village entrance, but in the night one could still hear the sound of the geckos, ‘this century-long exile of the tokay geckos’ . . .

By putting words to the page, the village scribe is preserving the story of his people, and a way of life that is disappearing under the weight of modernization, but he is not alone in his task—the ghosts of his loved ones, now gone from this life, visit him still. In his words and his visions, dead live on.

For all the sorrow running through it, Chronicles of a Village shimmers with a unique beauty, one that runs clear and crisp against a misty backdrop. Translator Quyên Nguyễn-Hoàng has taken great care with the selection of words, creating unique expressions when needed, to best reflect meanings that do not have a direct English equivalent. In a conversation with Alex Tan that can be found here at Minor Literature[s],she shares her approach to some of the language and literary aspects of the original and talks about translation as she understands it.

Chronicles of a Village by Nguyễn Thanh Hiện is translated from the Vietnamese by Quyên Nguyễn-Hoàng and published by Yale University Press.