Grey cloud grasping light,

unrolling the softness of another world

towards the wobbling plane wing; its folds ripple,

someone has scattered seeds in each furrow.Who’s thinking, underneath the clouds,

how hard it is to restore the life of a flower,

when rain never coincides with favorable winds.But we have a shred of light.

Today, passing through a mid-gate

as if remembering.(from “Introspection on a Cloud” by Du Lulu, translated by Dave Haysom)

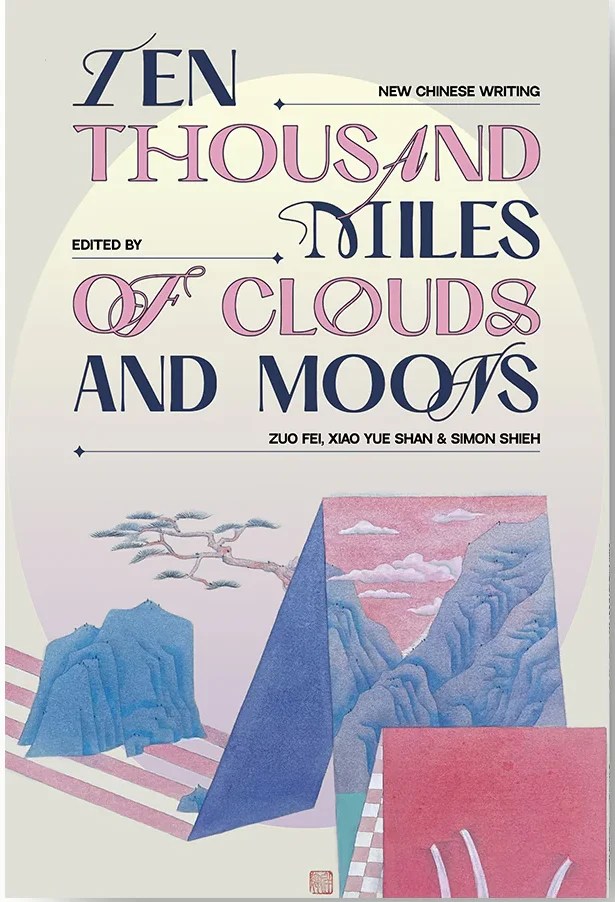

What exactly does it mean to enter into another world, to open oneself to a landscape at once familiar and strange? That is, one might suggest, one of the functions of literature. But if the map that grants access to that other world with its many artistic and cultural riches is in another language, translation is the key. For the editors of Ten Thousand Miles of Clouds and Moons, a collaboration between Beijing-based Spittoon Literary Magazine, a dual-language journal of contemporary Chinese literature, and Honford Star, the guiding inspiration for this first anthology project is, in keeping with that of the magazine, to seek out and bring into English translation, some of the most original, exquisite, and daring voices—new and established—contributing to the present literary landscape in China.

The introduction lays out the vision that guided their selection of pieces

The introduction lays out the vision that guided their selection of pieces

The work had to be excellent; the writer had to have a point of view that is under-explored in the Anglosphere; there had to be a balance of genders; and the language had to be so special that it has the potential to torture translators. This final aspect came only from our love for the Chinese language—which, like all languages, has a singular soul, a force drawn from its age and its malleability throughout time. The more a writer is able to tap into that soul, the more difficult the piece would inevitably be to translate.

Thus sixteen contributors—eight writers of fiction, six poets, and two essayists—were paired with eighteen translators, to offer readers a journey that covers a wide literary terrain. You will find yourself in a world with a long rich cultural history and traditions, and you will find stories that depict a modern society that Western, English language readers will instantly recognize, with influences drawn from an international well of literary sources. You will find work that pays homage to the China’s past and tales that turn on distinctly futuristic, apocalyptic visions. And surreal, experimental tones alongside traditional Chinese poetic form.

The opening story in the compilation sets the mood perfectly. A piece of dystopian science fiction that revolves around the fate of the 18th century work considered the greatest of all Chinese novels, “Mass in Dream of the Red Chamber” by Chen Chuncheng (translated by Xiao Yue Shan) is set in the far future—the 4800s—at a time when this great work of literature is not only lost, but any effort to retrieve its contents or storyline are strictly forbidden. There is, at this time, a belief that the text was completed at the peak of the universe’s development, and that all had begun to decline and dissipate since that time. The narrative follows the recorded account of a prisoner, a man born in 1982, who fell into a deep coma for several thousand years, only to miraculously awake and find himself as a specimen in a museum exhibit. He becomes a kind of missing link to the lost masterpiece for a clandestine organization desperate to recreate, as much as possible, the original; its preservation being essential to the continued existence of the universe itself. But that also makes him, and those who come to hear him access his memories of the text, the target of murderous government forces. It is a wonderful meeting of the glory of past achievements and the horrors of a post-apocalyptic totalitarian future, connected with an out-of-time protagonist’s personal recollections of life in the 1990s and 2000s.

The settings of the tales that follow vary, from a contemporary urban environment where bored youth hang out and make trouble, to the account of family history, to a mystical encounter on a mountainside. The energy shifts from story to story, often turning to the unexpected, cracking the fragile veneer of reality. Particularly delightful is the excerpt from Lu Yuan’s novella The Large Moon and Other Affairs (translated by Ana Padilla Fornieles), a piece of weird fiction that reflects, perhaps, in its magical strangeness, the influence of Bruno Schulz whose work the author has translated. As the moon, being pulled toward the earth, grows larger and larger in the sky, the eccentric Mr. Lu struggles with insomnia and troubled dreams. One night, having taken a concoction to aid his sleep, he finds himself carried off on a nocturnal adventure through the skies:

Mr. Lu rose from the valley of dreams and rowed out the window, picturing himself an unthinking mycoplankton or a sea cow, heading back to the Amazon River Delta. Riding upon the clouds and the wind with neither a northeastern wife nor a Vietnamese mistress at his side, the invoices seeking his death yet to arrive, and the murderous plots working their shapeless, invisible night shifts had been temporarily put on hold. There were no cold, mechanical alarms, no greasy company breakfasts, and definitely no covetous relatives, neighbours, acquaintances, or colleagues. The naked Mr. Lu, wearing only a heavy pair of plastic slippers, flew over the sparse suburban streetlights, bounding towards the corridors of stars spiraling in a snail-shell pattern along the horizon’s towers. A thin sheet of air gently caressed his bulging beer belly, and the city was as far away as a firefly, succumbing to the hallucinatory bird’s eye view of inebriated men.

The two nonfiction pieces add a welcome new dimension to the collection. Hei Tao’s “Three Essays” (translated by Simon Shieh and Irene Chen) paint delicate portraits of southern China, and a lifestyle that is gradually disappearing, while Mao Jian’s “No One Sees the Grasses Growing” is a relatable, and humorous, memoir of her years as a student at East China Normal University in Shanghai in the 1980s and 90s. She recalls a time when students paid less attention to their studies than might have been wise. They were young and in love with a certain literary coolness. Her first degree was in Foreign Languages, but she found it hard to resist the allure of another course of study:

The truth is, in the eighties, it was impossible to resist the passions of the Chinese Department. The notice boards were plastered with adverts promoting literary lectures, and all sorts of clubs and societies adopted the grandiose affectations of belles-lettres, prancing about the center of campus. If someone were to ask you about going corporate after graduation, you’d have to self-reflect on the unrefined impression you must have been giving off. Those years were the golden age of Casanovas, who made names for themselves by proclaiming their undying love for poetry, and any girl who could be moved by Rilke would inevitably enter into a spontaneous fling with one of these campus poets.

It was an era of living away from home, first trips to KFC, young love, and inspiring and unconventional professors. But looking back decades later, now a professor herself at the same institution, she realizes that that time is past, in so many different ways.

Spread out among the prose pieces, are the contributions of the poets, three poems each. This arrangement works very well, offering a change of pace and granting each poet the space to have their unique voice heard. As with the fiction and nonfiction, there is both variety and, of course, precise, evocative imagery that is at once modern, yet with an echo of the long-standing traditions of Chinese verse.

Anthologies can be uneven projects, but this selection of new Chinese writing is strong, varied, and continually fresh and surprising from beginning to end. The contributors range in age, with the youngest in his mid-twenties, the oldest in his mid-sixties. Their work is consistently fresh and vibrant, and the translators all appear to have produced results that feel effortless. It should also be noted that this volume is beautifully presented, with a simple, yet elegant design. This is an endlessly engaging collection for anyone with an interest in contemporary Chinese literature, especially if you are seeking work that challenges expectations.

Ten Thousand Miles of Clouds and Moons: New Chinese Writing is edited by Zuo Fei, Xiao Yue Shan and Simon Shieh, and published by Spittoon Literary Magazine in collaboration with Honford Star