Some writers pass through your reading life and move on, perhaps appearing by chance now and then over the years, others ignite a clear desire to read more, if not all, that you can get hold of. That might be a small library of volumes to collect, but for those of us drawn to writers in translation—writers we often discover as a direct result of following a known or trusted translator—it can mean watching and waiting for more work to slowly emerge in English.

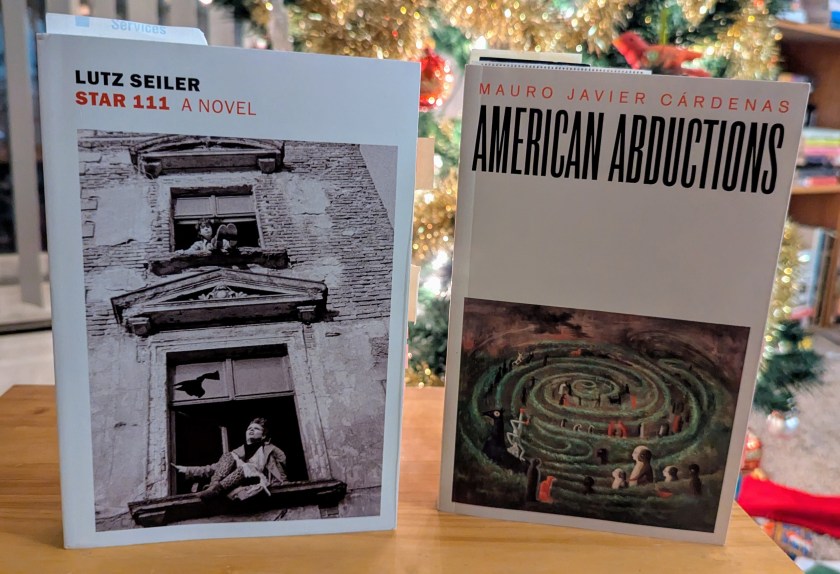

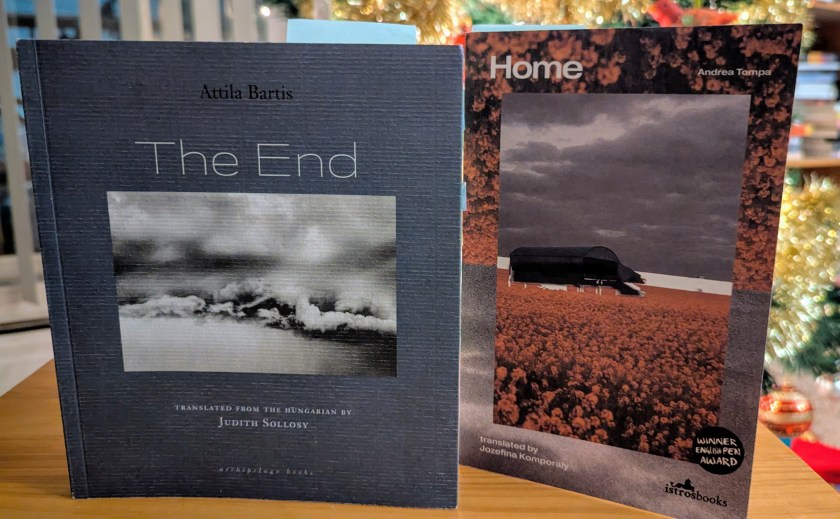

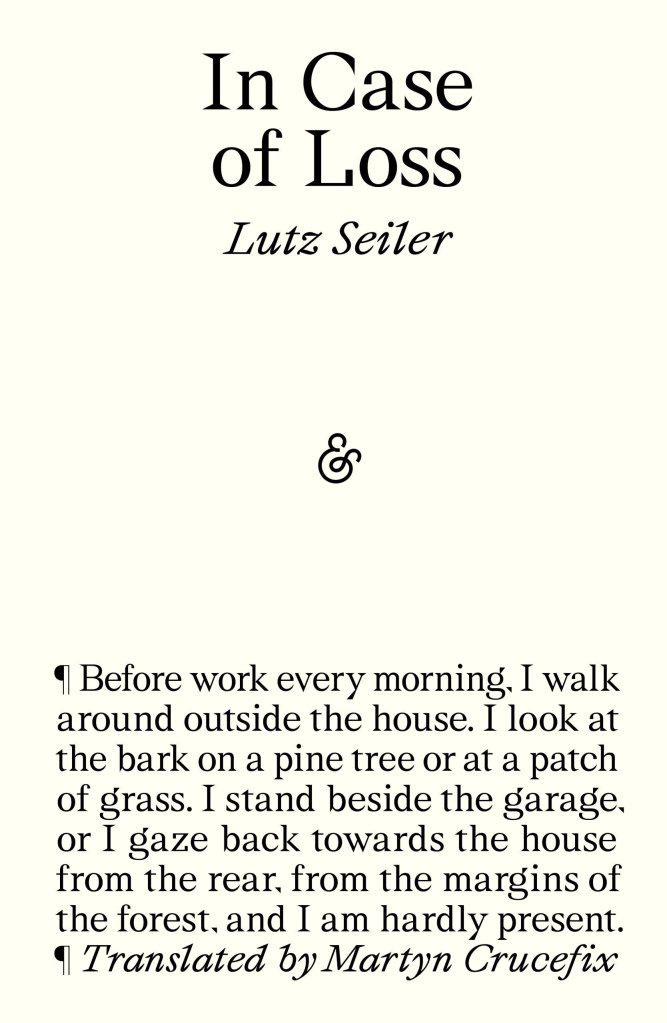

For me, one such writer is German poet, essayist and novelist Lutz Seiler. I first encountered his poetry about two and half years ago through Alexander Booth’s translation of his 2010 collection in field latin. At the time, the only other title available was his first novel Kruso which was, when I first checked, out of stock. Yet, when UK publisher And Other Stories announced they would be publishing Seiler’s debut poetry collection, Pitch & Glint, his second novel, Star 111, and a collection of essays, In Case of Loss, in late 2023, I took note. Then, when I had the opportunity to read Star 111 this year in advance of its North American release from NYRB in October, I quickly set about acquiring his other work. And, as these things go, while reading the poetry and the essays, I was inspired to add work by two of the poets Seiler writes about or honours—but more about that later.

Born in the Thuringia region of the GDR in 1963, Seiler’s poetry is rooted in the rural landscape of his childhood, scarred by years of uranium mining, sensitive to place and relationship to family, as child and as a parent. However, unlike many writers, he had no interest in books or literature when he himself was young. He did not start reading poetry until he was completing his mandatory military service in his early twenties, having already trained as a bricklayer and carpenter. He was certainly not writing, not even jotting the odd observation down, but something was brewing. As he says in his essay “Aurora: An Attempt to Answer the Question ‘Where is the Poem Going Today?’”:

Born in the Thuringia region of the GDR in 1963, Seiler’s poetry is rooted in the rural landscape of his childhood, scarred by years of uranium mining, sensitive to place and relationship to family, as child and as a parent. However, unlike many writers, he had no interest in books or literature when he himself was young. He did not start reading poetry until he was completing his mandatory military service in his early twenties, having already trained as a bricklayer and carpenter. He was certainly not writing, not even jotting the odd observation down, but something was brewing. As he says in his essay “Aurora: An Attempt to Answer the Question ‘Where is the Poem Going Today?’”:

Yet a good ten years later, I wrote poems that had been, in that earlier period, when poetry did not feature in my life, gathering and storing their subject matter, their materials. Doubly hidden from me at the time, clearly the poems had been, even then, making their way towards me. What is different these days is that I have become more conscious of the signs of a poem being on its way. I am aware of what situations, materials and substances it might respond to, what it is likely to ingest—for later use.

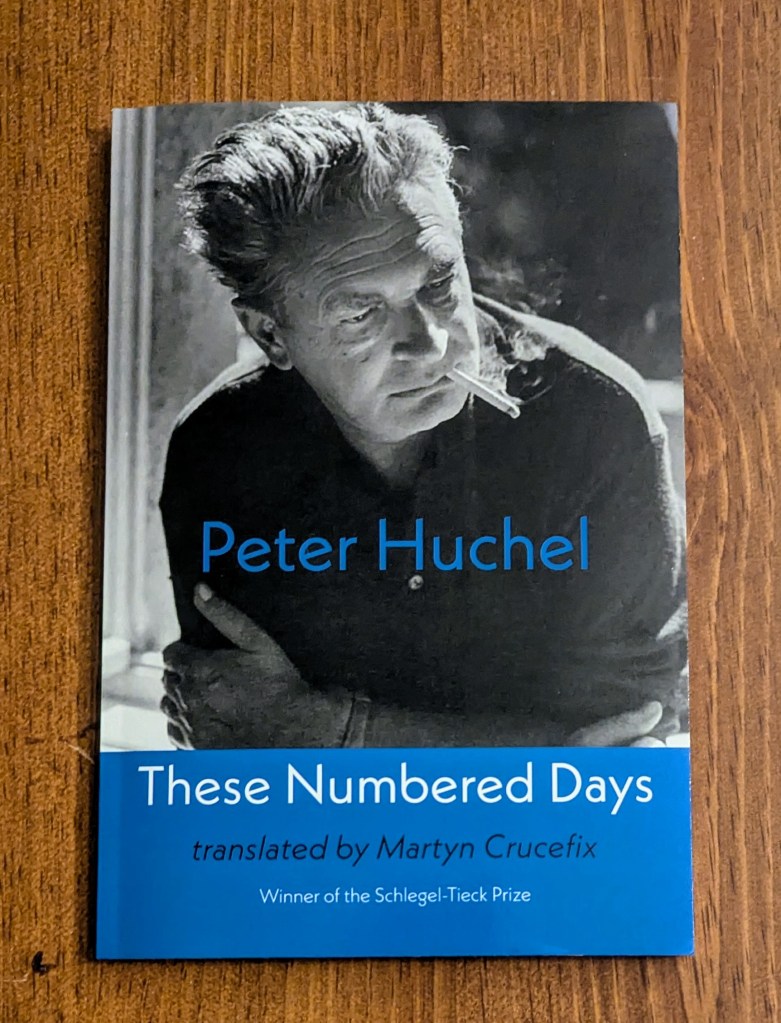

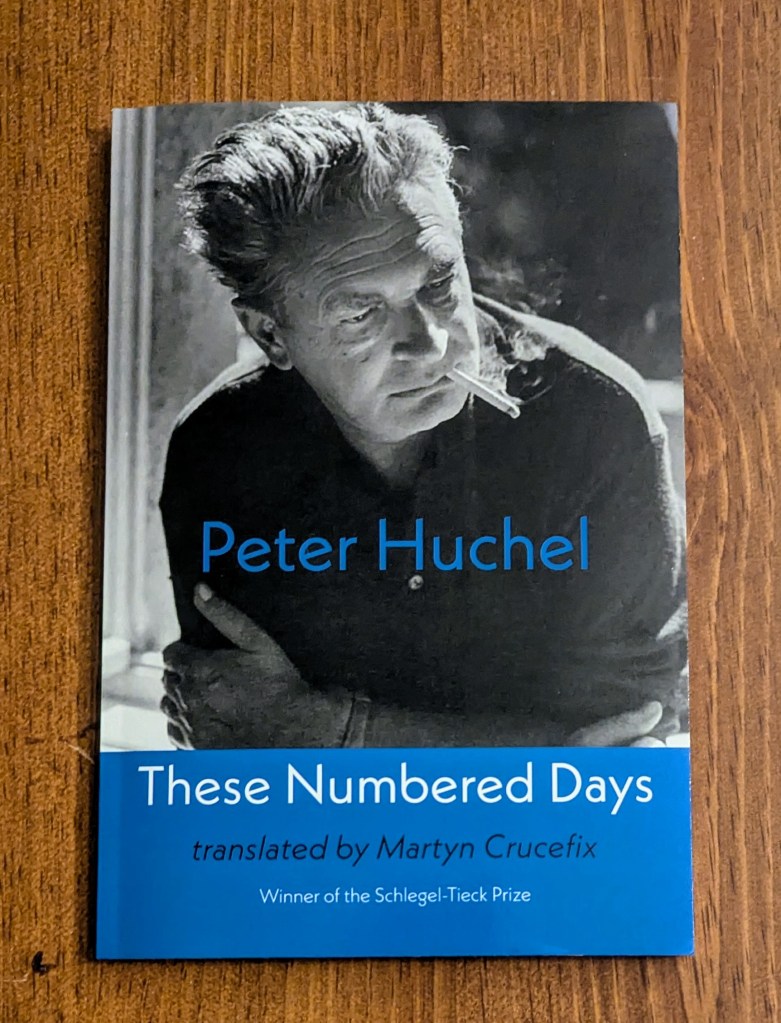

For a poet who came to literature somewhat unexpectedly, Seiler’s writing about writing, and about the poetic art and process is excellent, presumably of interest to other poets, but also, and perhaps more critically, for those of us who enjoy poetry but sometimes feel inadequate to examine a poem without a strong literary vocabulary and the requisite coursework (assumed to be) required to read and write it. In Case of Loss contains several essays about the work of other poets. One, Peter Huchel (1903–1981), was new to me. I was aware that Seiler is the custodian of the Huchel House in Wilhelmhorst near Berlin, but knew nothing of Huchel himself, one of the most an important German poets of the post-war era who ended up running afoul of the government of the GDR and was eventually allowed to migrate to the West. The title essay is an account of Seiler’s first impressions of the house itself after breaking in with Huchel’s widow’s blessing and his coming into possession of a notebook the poet kept all his life in which he recorded images, metaphors, lines, and tentative sketches, all categorized by theme. The manner in which Seiler traces some of the formative elements that will, often years later, appear as shadows or echoes in a finished piece is fascinating and a testament to the gestation period a poem can have.  Of course, I wanted to read more, so I sought out These Numbered Days, Huchel’s 1972 collection, released in 2019 in an award winning English translation by Martin Crucefix (who is also the translator of In Case of Loss). His poetry often draws on the landscape of his youth for atmosphere frequently in concert with mythological, historical, and Biblical images to create crisp, even chilling poems. Although they are generally spare, one can sense that they have been carefully shaped and honed over time, each word or phrase carrying much weight, very often political—something confirmed by both Seiler’s insights, Crucefix’s notes, and Karen Leeder’s Introduction.

Of course, I wanted to read more, so I sought out These Numbered Days, Huchel’s 1972 collection, released in 2019 in an award winning English translation by Martin Crucefix (who is also the translator of In Case of Loss). His poetry often draws on the landscape of his youth for atmosphere frequently in concert with mythological, historical, and Biblical images to create crisp, even chilling poems. Although they are generally spare, one can sense that they have been carefully shaped and honed over time, each word or phrase carrying much weight, very often political—something confirmed by both Seiler’s insights, Crucefix’s notes, and Karen Leeder’s Introduction.

At the edge of the village the wind

flung its ton of frost

against the wall.

The moon lowered a fibrous gauze

on the wounds of the rooftops.

Slowly the emptiness of night descended,

filled with the howling of dogs.

Defeat sank

into the frozen veins of the country,

into the leather-upholstered seats

of old Kresmers in the coach sheds,

between the horse tack and grey straw

where children slept.

(Peter Huchel — from “Defeat”)

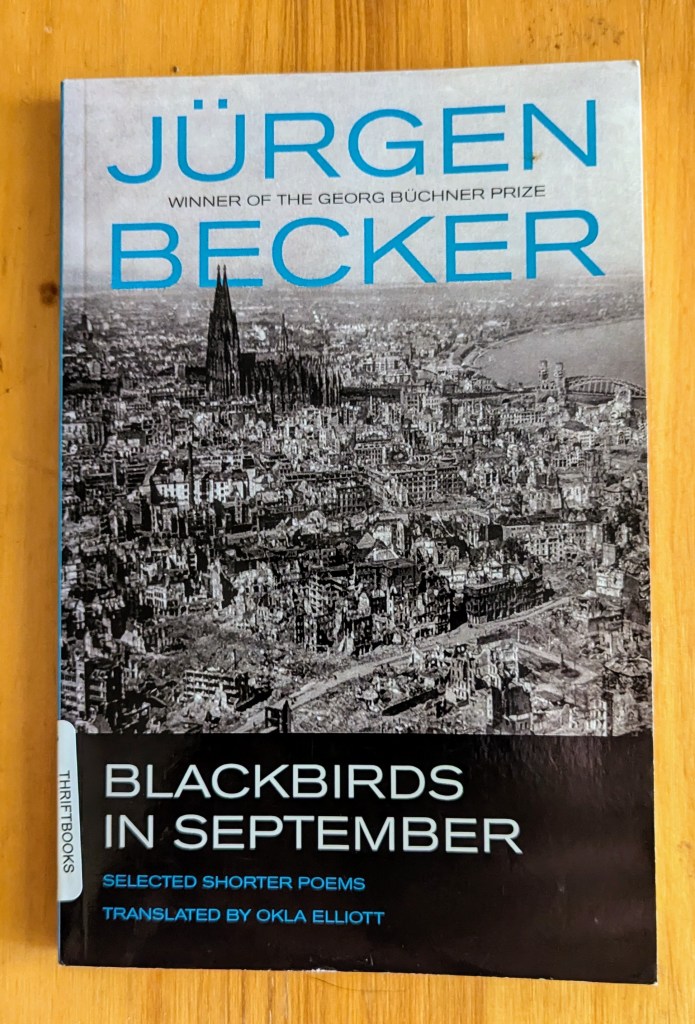

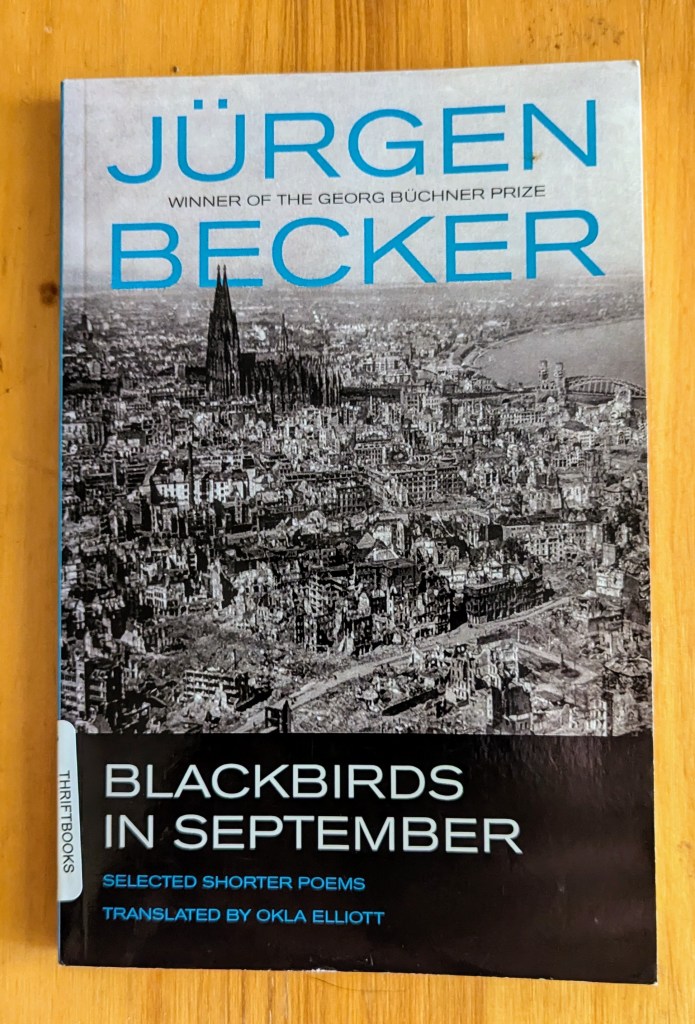

In addition to an unusual back to front reading of a book by Ernst Meister, the other poet Seiler devotes an essay to is Jürgen Becker. I had already read Becker’s fragmentary poetic novel, The Sea in the Radio, but a dedication to the poet (who very recently passed away) in Seiler’s collection Pitch & Glint,  called to mind a collection of selected shorter poems, Blackbirds in September, which I was able to track down and read alongside the essay “’The Post-War Era Never Ends’: On Jürgen Becker.” Here Seiler takes a more personal approach acknowledging Becker’s influence and his own friendship with the older established poet. He traces his own process of learning to read and appreciate Becker’s poetry. Born in Cologne in 1932, Becker was a member of Group 47, the organization formed to promote young German writers after the war. He employed an experimental, open form of writing with an emphasis on landscape and the persistence of memories of the war in German land and history. His language tends to be spare and his poems have a calm, light feel, but that is only the surface.

called to mind a collection of selected shorter poems, Blackbirds in September, which I was able to track down and read alongside the essay “’The Post-War Era Never Ends’: On Jürgen Becker.” Here Seiler takes a more personal approach acknowledging Becker’s influence and his own friendship with the older established poet. He traces his own process of learning to read and appreciate Becker’s poetry. Born in Cologne in 1932, Becker was a member of Group 47, the organization formed to promote young German writers after the war. He employed an experimental, open form of writing with an emphasis on landscape and the persistence of memories of the war in German land and history. His language tends to be spare and his poems have a calm, light feel, but that is only the surface.

But the landscape is rather quiet.

Invisible the destruction, if in fact

there is destruction.

And the time is passed

which the subsequent, the subsequent time produced.

But you never speak of Now.

Probably in the summer. At that time of year

we remember. Fence posts follow the paths,

or turned around, all of it belonging

to the landscape . . . who owns it? The landscape

leads into landscapes, from the visible ones

to the invisible ones which await us.

(Jürgen Becker — from “A Provisional Topography”/translated by Okla Elliott)

Other essays of particular interest in this collection (which gathers a selection of Seiler’s nonfiction from across twenty-five years) include “Illegal Exit, Gera (East),” a return in memory and in more recent years to a landscape that is being transformed and remediated, and “The Tired Territory” which begins as an exploration of the history of uranium mining in his home state, but turns into a meditation on the distinct poetic sensibilities that he had to define for himself after what he describes as the difficulties encountered in his “brief career as a doctoral student in literary studies.” The categories that hold his fascination are intangible: heaviness, absence, tiredness. Understanding this for himself is essential:

Writing poetry: a difficult way to live and, at the same time, the only possible way.

One aspect of all this is that the poem engages specifically with what cannot be verbalised. The mute and non-paraphrasable and its unique, existential origin: the particular qualities of any poem arise from these two subtly interwoven elements. The poem travels towards the unsayable, yet this is a movement without an end.

It is not only the reading and writing of poetry that slips into Seiler’s essays—to a greater or lesser extent—but the final piece tackles his slow transition to prose. “The Soggy Hems of His Soviet Trousers: Image as a Way into the Narration of the Past” chronicles the year he moved with his wife and children to Rome for a period of dedicated novel writing. He dragged along boxes and boxes of books, research and paraphernalia he had gathered in preparation for the writing of his first novel. He’d planned to draw heavily on his own experiences moving to Berlin in the aftermath of the fall of the Wall and the more he describes his intentions, the more it sounds like what would eventually become his second novel, Star 111. But it’s only 2011 and our would-be novelist is staring at an empty page day after day. It is not until he finally gets out of his room, into the city, that everything changes. A suggestion that he write a short story set in a location he had not previously considered soon conjures forth an image so strong that ten pages become 500 and he has what will ultimately become his first novel Kruso.

Finally, if I return now to own Seiler’s poetry, in field latin and his debut collection from 2000, Pitch & Glint, more recently released in Stefan Tobler’s translation, many of the allusions in individual poems become clearer in light of having read his essays and the autobiographically influenced novel Star 111. But neither is necessary. Seiler’s poetry has a natural appeal. I wrote about in field latin here, and this earlier work (ten years separate the two volumes) is likewise rooted in the East Germany of the poet’s youth—the wildness, the strict schools, the land with its slag heaps and detritus of mining. Yet, for Seiler, the sound and rhythm are critical, as is the construction of images that move beyond the mere biographical. Darkness, frost, echoing footsteps recur. You can feel the chill:

Finally, if I return now to own Seiler’s poetry, in field latin and his debut collection from 2000, Pitch & Glint, more recently released in Stefan Tobler’s translation, many of the allusions in individual poems become clearer in light of having read his essays and the autobiographically influenced novel Star 111. But neither is necessary. Seiler’s poetry has a natural appeal. I wrote about in field latin here, and this earlier work (ten years separate the two volumes) is likewise rooted in the East Germany of the poet’s youth—the wildness, the strict schools, the land with its slag heaps and detritus of mining. Yet, for Seiler, the sound and rhythm are critical, as is the construction of images that move beyond the mere biographical. Darkness, frost, echoing footsteps recur. You can feel the chill:

wind came up the border

. dogs were rising on

their delicate branching skeletons

whistled a bewitching witless

wanderlied. the snow came in

& tore the iron

curtain of their eyes, a

blunted gaze towards the hinterland

and made plain that we do.

(— from “in the east of the land”)

Seiler’s characteristic use of lower case letters and ampersands (especially striking in German where nouns are capitalized) adds to the mood and intensity of his poetry. One of the blurbs on the back of Pitch & Glint describes it as “a real-world Stalker with line breaks.” That captures the feel well.

The beauty of reading a number of works—nonfiction, fiction and poetry— that intersect like this is that each individual experience is heightened. Seiler’s poetry and fiction easily stand on their own, but the essays add an extra dimension. To be fair, one’s enjoyment of this collection may depend on whether one is a poet, or interested in poetry and the process of poetic inspiration/creation, or familiar with his other work. Nonetheless, his essays are thoughtful with a very strong personal flow and reflect the mind and experiences of a man for whom poetry is central to his very existence—in his memories, in his specific creative pursuits, and even in the everyday act of taking his daughter to dance lessons or son to football practice.

In Case of Loss and Pitch & Glint by Lutz Seiler are translated from the German by Martin Crucefix and Stefan Tobler respectively and published by And Other Stories. These Numbered Days by Peter Huchel is translated from the German by Martin Crucefix with and Introduction by Karen Leeder and published by Shearsman Books, and Blackbirds in September by Jürgen Becker is translated from the German by Okla Elliott and published by Black Lawrence Press.

Other titles mentioned and reviewed earlier on this site are Star 111 (And Other Stories/NYRB Imprints) and in field latin (Seagull Books), both by Lutz Seiler, translated from the German by Tess Lewis and Alexander Booth respectively.

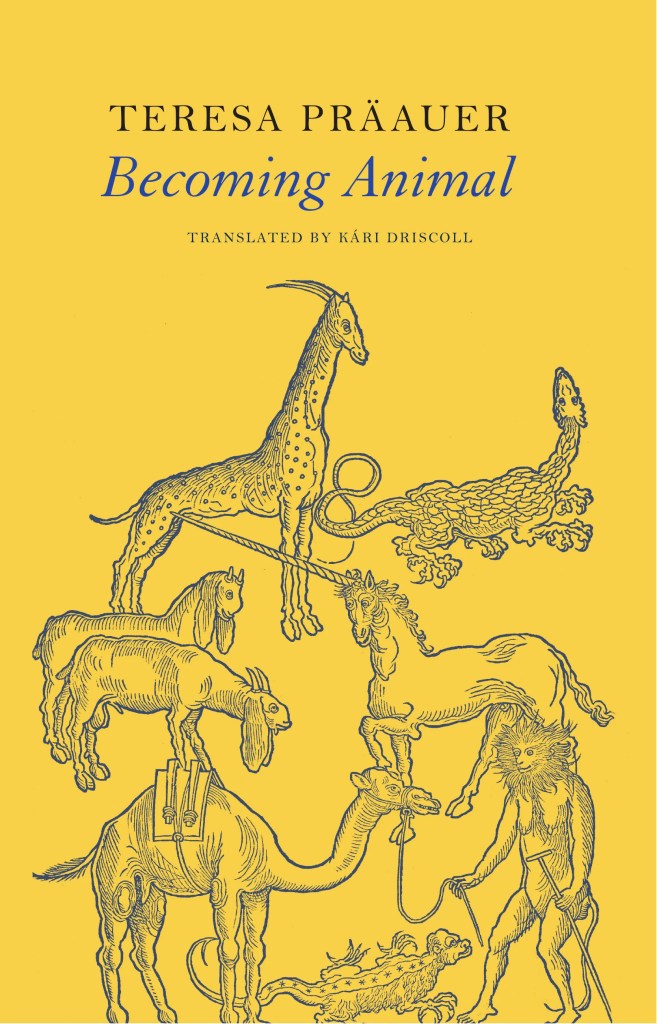

Präauer begins with the harpy, one of the most distinctive figures to appear time and again in early efforts to catalogue all known living beings—factual, mythological, and “exotic” alike—that occupied artists and thinkers from the Medieval era on into the Age of Discovery.

Präauer begins with the harpy, one of the most distinctive figures to appear time and again in early efforts to catalogue all known living beings—factual, mythological, and “exotic” alike—that occupied artists and thinkers from the Medieval era on into the Age of Discovery.