I don’t know what I expected when this year began. Ever since 2020 it seems we have greeted each year with some measure of optimism—I mean how could it be worse than the one that just passed? And somehow, each year has managed to be worse in some new, unanticipated way. 2025 saw the continuation of conflict, famine, destruction, climate catastrophes. We also witnessed the further escalation of intolerance, racism, sexism, anti-trans sentiment, religious fundamentalism, and autocratic politics. Where I am in western Canada we have witnessed all of this, not just from our neighbours to the south, or distant nations, but right here close to home. It is hard not to lose hope, but giving up is not an option and so, 2026, here we come, preparing for the worst but dreaming of the best.

Personally, I struggled a bit this year. Family stuff, some depression, and, in late November, a car accident that has left me with stiffness and pain that is slow to subside. But, on the bright(er) side, my focus and concentration has returned, and replacing my damaged car proved easier than it might have been. My old Honda Fit had more value than I expected, and I happened to see a (newer) used vehicle that fit my needs for a very good price and was fortunately in the position to buy it. If the police manage to find the impaired driver who hit me (assuming she was insured) I will even get my deductible back. But, quite honestly, I’ll be happy to be able to look over my left shoulder again!

As for reading/reviewing, 2025 was a mixed year. I had a few off times when I struggled to finish books (or gave up altogether), and a number of mediocre reads passed without public mention. At the same time, I read some excellent poetry in English, but could not find the words to write coherent reviews. For some reason, I feel I lack the knowledge and vocabulary to say the “right” thing about poetry in my own language—I feel more comfortable responding to translations. And I did read a lot of poetry in translation this year.

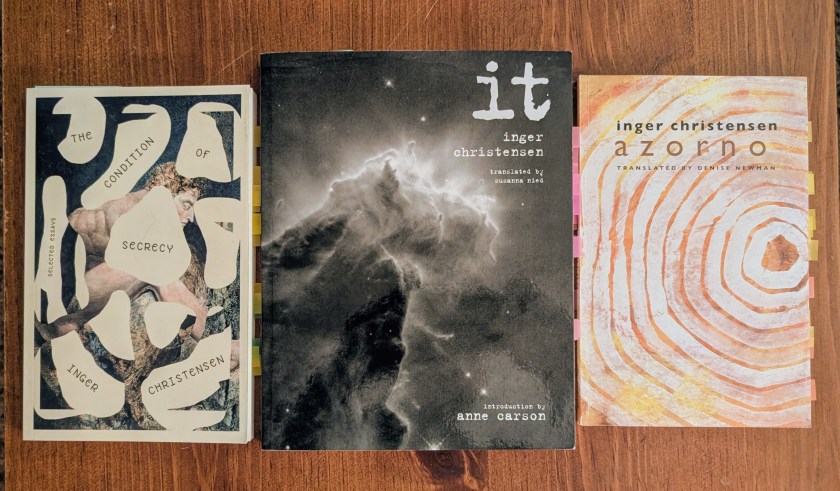

Looking back over 2025, the singular defining force for me was the work of Danish experimental poet and writer Inger Christensen (1935–2009). In January I read her essay collection The Condition of Secrecy, and I was immediately entranced by her love of language and her view of the world as informed by science, nature, music, and mathematics. I knew I wanted to read all of her poetry and fiction and, throughout the year, that is exactly what I did. I read eight of her translated works and only have one left to obtain although I have a dual language edition of one of the sequences in that volume (“Butterfly Valley”). Along the way I also decided I wanted to learn to read Danish as there are elements of her work that simply cannot be reproduced in translation (mathematical constraints in particular).

And so, I am learning Danish, or, should I say, jeg lærer dansk.

Although I enjoyed all of her books, my favourite piece of fiction was the crazy word play mystery Azorno (1967) and my favourite work of poetry was her monumental it/det (1969), both earlier works. Of course, the wonderful book length poem alphabet (1981) is also amazing. Her poetry and essays are translated by Susanna Nied, her fiction by Denise Newman.

Some thoughts about a few of my other favourite reads from the past year:

Some thoughts about a few of my other favourite reads from the past year:

Prose:

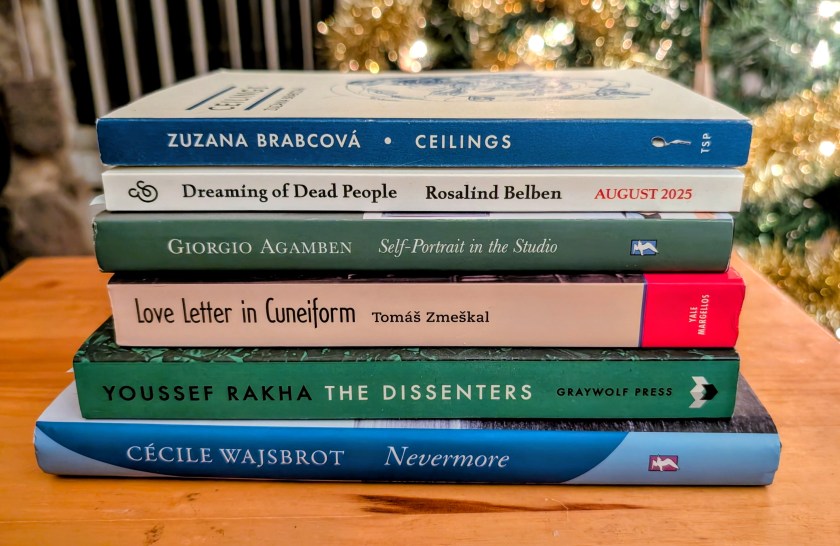

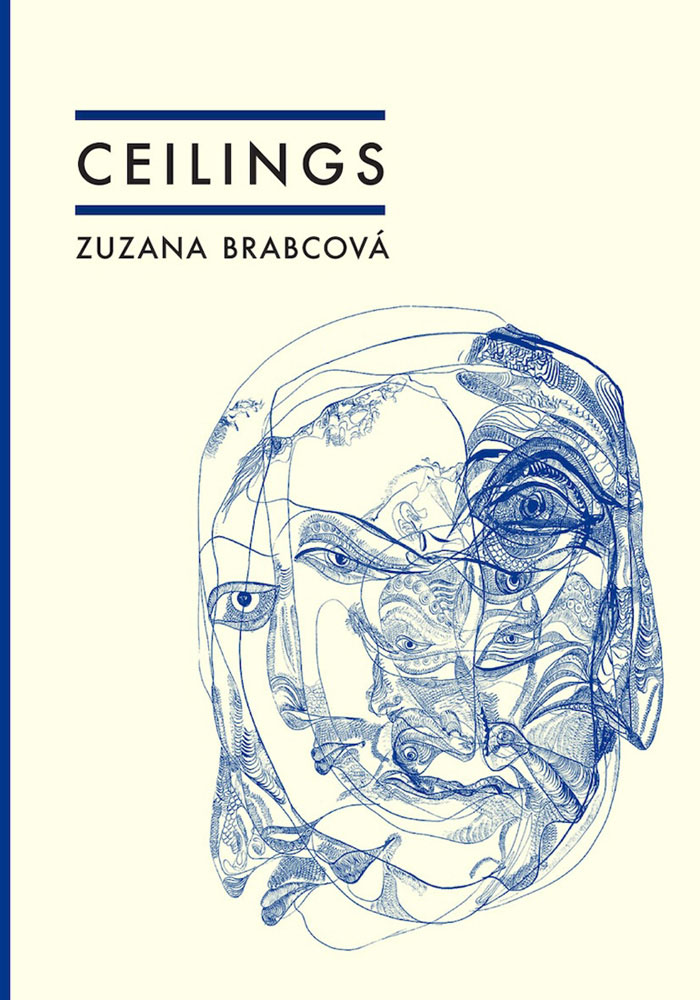

Ceilings – Zuzana Brabcová (translated from the Czech by Tereza Veverka Novická)

Set on the detox ward of a psychiatric hospital in Prague, Brabcová captures the institutional environment and the strangeness of psychotic interludes with the skill only personal experience can provide. This wild and delirious ride pulled me out of a reading slump.

Dreaming of Dead People – Rosalind Belben

I read two novels by Rosalind Belben this year, The Limit which was re-issued by NYRB Classics several years ago and this one which was re-issued by And Other Stories this year. Both are strange in a brutal yet beautiful way, but Dreaming is, to me, a more accomplished, in depth novel.

Love Letter in Cuneiform – Tomáš Zmeškal (translated from the Czech by Alex Zucker)

One of those books I’ve been meaning to read for years and when I finally picked it up off the shelf, I was delighted to find out how funny and weird this multi-generational family drama truly is. Zmeškal lends magical realism and historical reality with a cast of eccentric characters to create a memorable tale.

Self-Portrait in the Studio – Giorgio Agamben (translated from the Italian by Kevin Attell)

Far from a conventional memoir, Agamben invites his reader on a tour of the various studios he has occupied over the years, reflecting on the people, books, and places that come to mind along the way. A surprisingly engaging work.

The Dissenters – Youssef Rakha

The final two novels on my list are both highly inventive in style and form. Egyptian writer Youssef Rakha’s first novel written in English manages to seamlessly incorporate Arabic expressions without explanation, adding to the richness of this original, multi-dimensional story of one remarkable woman set against the events of recent Egyptian history. Endlessly rewarding.

Nevermore – Cécile Wajsbrot (translated from the French by Tess Lewis)

This ambitious novel is a moving evocation of loss and change. A translator has come to Dresden to work on a translation of the central “Time Passes” section of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse from English into French. Reflections on change and transformation drawn from her own state in life and various historical events accompany the process of translation.

Of Desire and Decarceration – Charline Lambert (translated from the French by John Taylor)

It is most unusual for a poet as young as Lambert (b. 1989) to see her first four volumes of poetry published together so early in her career, but translator John Taylor felt that the Belgian poet’s books show a natural growth best appreciated as a whole. He is not wrong (he is also a translator whose judgement I always trust).

Psyche Running: Selected Poems 2005–2022 – Durs Grünbein (translated from the German by Karen Leeder)

This selection of poetry rightfully won the Griffin Prize this past year. Grünbein’s work tends to draw on his hometown of Dresden and Italy where he now spends much time, and this selection presents a good introduction to the variety of his mid-career work. One can only hope that the attention he has received with this book will lead to full translations of more of his work.

arabic, between love and war – Norah Alkharrashi and Yasmine Haj (eds)

The first of a new translation series by Toronto-based trace press, this selection of original poems with their translations—most written in Arabic, with some written in English and translated into Arabic, exists as a kind of conversation between poets from across the Arabic speaking world and its diaspora. Vital work.

The Minotaur’s Daughter – Eva Luka (translated from the Slovak by James Sutherland-Smith)

This book, a complete surprise tucked into a package from Seagull Books, is a delight. Luka’s world is a strange and quirky one, transgressive and fantastic. Leonora Carrington is a huge influence, with a number of ekphrastic poems inspired by her paintings but given life from Luka’s own unique angle. Loved it!

Ancient Algorithms – Katrine Øgaard Jensen (with Ursula Andkjær Olsen and others)

This is the book that marked my return to reading post-accident. And how could it not. Jensen’s translations of Olsen’s poetic trilogy are very close to my heart. This unique work begins with poems selected from those books (in the original Danish), followed by Jensen’s translations, which set the stage for a series of collaborative mistranslations guided by rules set by the various poet translators involved. A wonderful celebration of poetry and translation and the necessary bond between the two.

My Heresies – Alina Stefanescu

Finally, one of the English language poetry collections I read and did not review (I did have a great title though). Alina Stefanescu breathes poetry as a matter of course, as is clear to anyone who has had an opportunity to engage with her online. There is an infectious defiance to this collection which straddles Romania and America, conjures angels and demons, and explores the everyday reality of romantic and parental love. I connected most directly with wry observations of motherhood that resonated with my own less than conventional parental existence.

There are, as ever, many other books I read this year that could have made this year end review. You’ll have to check my blog to find them!

There are, as ever, many other books I read this year that could have made this year end review. You’ll have to check my blog to find them!

Happy new year!