I’m growing old. Where have all those beautiful years gone, when I hung out with my mates and we roamed the pool halls and sleazy bars on Paission or the cafes in Saint Andrew Square like cowboys, with a Marlboro hanging from our lips and a flat metal hip flask with whisky in the back pocket … There goes youth, there goes beauty, never to return.

When we meet Stratos Achtidis, he is trying to pinpoint where is life went off the rails, but he is not exactly in the mood for soul searching. Rather he recalls that weekend when, irritated and hungover, he got angry at the cats his wife had brought home for the children, and ended up tossing them off the balcony. A horrified neighbour saw them fall to the street. But then horrifying his neighbours, not to mention regularly and generally annoying them, was something Stratos had long perfected. And that incident alone is not the end of his marriage, not yet, but his long suffering wife , Sotiria, will not put up with much more. And it’s as good a place as any for Stratos to anchor the tale he has to tell.

Call Me Stratos by Chrysoula Georgoula is the unflinching portrait of the social and economic dynamics and tensions that have impacted ordinary working-class Greek people over the past two decades, from the heady run-up to the 2004 Summer Olympic Games, through the devastating years of the economic crisis, to the increased pressures of migration, and the rise of the Golden Dawn. It is a story at once specific to Athens—defined and traced on the streets of one small area of the city—that is now echoing widely in communities and countries worldwide. However, this not an account relayed and assessed from afar. Rather, Georgoula entrusts the narrative to a man who is proud, stubborn, coarse, and self-destructive. And painfully human.

Call Me Stratos by Chrysoula Georgoula is the unflinching portrait of the social and economic dynamics and tensions that have impacted ordinary working-class Greek people over the past two decades, from the heady run-up to the 2004 Summer Olympic Games, through the devastating years of the economic crisis, to the increased pressures of migration, and the rise of the Golden Dawn. It is a story at once specific to Athens—defined and traced on the streets of one small area of the city—that is now echoing widely in communities and countries worldwide. However, this not an account relayed and assessed from afar. Rather, Georgoula entrusts the narrative to a man who is proud, stubborn, coarse, and self-destructive. And painfully human.

In his mid-40s at the time of his telling, Stratos is a man who has either lost or thrown away nearly everything positive that has come his way—a marriage and two children, a successful business, countless other job opportunities, and several chances to hold to his values, such as they are. The only person who never gives up on him, through joy and despair, is his mother whom he often refers to as Mrs. Nickie. She repeatedly bails him out, cleans up his messes, tries to reason with him, and, in the end, takes him back into his childhood home when his marriage ends.

Stratos narrates his story in short episodic chapters that read much like vignettes that are generally, but not entirely, chronological. The son of drinkers and bullies, he carries the family legacy on, even though he promises himself he will never hit his wife after the horrific physical abuse he witnessed his father unleash on his mother. Still, he is hot tempered, prone to obnoxious, sometimes violent, behaviour, and every time he manages to pull himself together long enough to achieve happiness and success, he is certain to undermine his gains. And when that happens, he is quick to blame everyone or everything else, typically retreating to his flat to drown his sorrows in alcohol and crank up the volume on his stereo so as to force his personal pity party on the entire neighbourhood. As a man who whose existence is contained within a particular district of familiar streets and businesses, and a circle of relatives and close friends, many of whom he has known since childhood, Stratos is both a legend and a victim in his own mind, unwinding an account (or is it a defense?) littered with crude language, sexist comments, and mildly racist remarks. He is not inclined to poetics or deep introspection—he rarely acknowledges his own agency—but he is conscious of a sensation he describes as brightly coloured pinballs that seem to come alive inside him whenever he is aroused or agitated. Like when his buddy uncovers his wife’s stashed bills and suggests a night out on the town:

“Tap, tap, tap” the happy fuchsia ball started bobbing up and down inside me. As though starting afresh and in better spirits, I put on my faded jeans with the wide black belt, the black sweater and the crocodile boots with the pointed toes, I rinsed and then combed back my curly hair and saw my eyes glowing like coals in the bathroom mirror. “Tap, tap, tap” the happy ball kept bobbing up and down inside me as I walked up Traleon with Memos beside me.

Looking back on the events that have marked his life—entering into the construction trade at an early age, meeting and marrying Sotiria, the birth of his two children, his establishment of a car wash and detailing service—Stratos’s account incorporates, with a measure of nostalgia, the myriad conflicts, pranks, and reckless activities that have arisen along the way. There are run-ins with the police, physical injuries, an ill-advised affair, and an endless string of debilitating hangovers. Through it all everyone smokes so much you can almost smell it. But he is, within the culture of machismo that shaped him, a fairly easy going man, especially in the periods when he manages to curtail his drinking. He holds no hard-line convictions. He even employs an illegal Syrian migrant at his car wash, a man so hardworking and reliable that he is able to keep the shop going and take on a lucrative roofing contract on the side that will, for a brief time, make him a very financially comfortable family man. But when things fall apart, they fall apart quickly and alcohol is frequently both trigger and consolation.

The worsening economic conditions in Greece ultimately take their toll. Stratos’s response to changing dynamics are, at first, primarily localized, related to observed changes in his business prospects and personal grievances. Then an old school friend roars into his life on his Harley, complaining about migrants taking all the jobs and soiling Greek culture and society, and boasting about his involvement with Golden Dawn. Stratos’s listless younger brother is easily seduced, but as his own marriage collapses and business dries up, he too will find himself looking for meaning and worth. Where he finds it is terrifying.

Call Me Stratos is a novel that offers no sense of closure. It hardly stops to catch its breath. The tone is relentless, and every situation and every character is filtered through Stratos’ biased, sometimes over-glorified, and often intoxicated perspective. He’s as reliable a narrator as he is honest with himself which makes him fascinating and tragic. And when he seems to have lost everything, he throws himself into an even more frightening world. In the end, Georgoula has created an unforgiving portrait that demonstrates how easy it is for one man, a certain type of man, to be drawn into a group he doesn’t really believe in, while indirectly taking into account, but not excusing, upbringing, social class, and shifting economic and political factors.

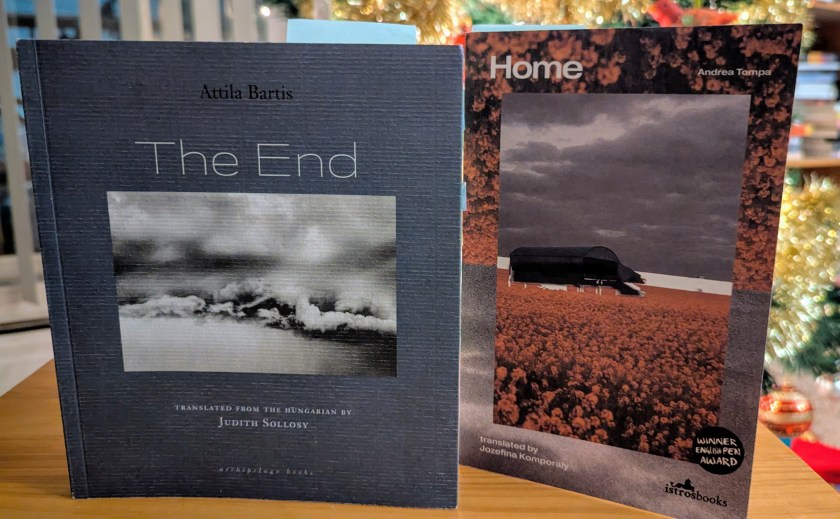

Call Me Stratos by Chrysoula Georgoula is translated from the Greek by Marianna Avouri and published by Istros Books.