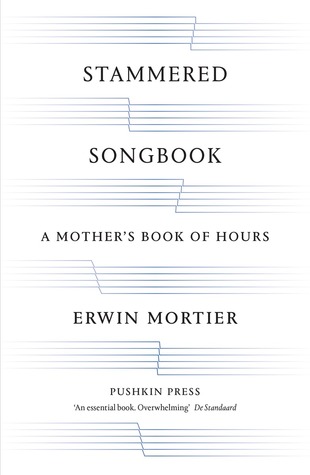

Once I became aware that this book existed, I knew I had to have it. So I ordered it immediately.

When it arrived and I went down to the bookstore to retrieve it (that is, release it from the bookseller who could not refrain from glancing through it as if he was regretting having to let it go), trusting some odd intuition that it might hint at something I was looking for. But, to be fair, I had little idea what to expect.

J’Lyn Chapman’s Beastlife is very small, fitting into the palm of the hand, or better yet, a pocket. An ideal companion for a walk in a park or natural area. I bought it with the idea that it might offer an unconventional provocation for a process of loosening, prying open, the closed window between my loss and the grief that I cannot begin to touch yet. At this point, in the first months following my parents’ deaths, mourning feels more like an empty space. Written of the body, mine and theirs. Confused. Contorted. Corporeal.

Not everyone would look to a book containing photographs of dead birds (albeit small, grainy black and white images), to find a voice for sorrow. For me it makes a strange sort of sense. It sounds morbid, but hopefully, if I manage to put to word the images that haunt my memories of my mother’s last month and days, I will be able to illustrate the beauty. If I have learned anything yet in these early days following the first significant losses of my life, it is that making sense of the death of those closest to us is at once universal and specific. And I lost both parents. Two very different relationships, two different circumstances, two separate yet entwined experiences of grief.

Not everyone would look to a book containing photographs of dead birds (albeit small, grainy black and white images), to find a voice for sorrow. For me it makes a strange sort of sense. It sounds morbid, but hopefully, if I manage to put to word the images that haunt my memories of my mother’s last month and days, I will be able to illustrate the beauty. If I have learned anything yet in these early days following the first significant losses of my life, it is that making sense of the death of those closest to us is at once universal and specific. And I lost both parents. Two very different relationships, two different circumstances, two separate yet entwined experiences of grief.

Of course, there is much more to Beastlife than photographs of birds.

This collection of essays—poetic meditations—on life and death, birds and beasts, and our human interaction with the natural world offers evocative, yet insistent reminders that we should strive to observe, engage with, and exist in this world with grace and compassion. Not that we, as humans, always succeed. Sometimes we are careless. And sometimes we are unthinkably cruel—inhuman even.

Death is a theme throughout, up close and afar. And violence too. Chapman explores the ways we intersect with nature—as hunters, naturalists, observers of atrocities, and, most fundamentally perhaps, bearers of new life. This tiny volume challenges the readers to reflect on our place in the cycle of life, in the beauty and the pain.

For me, at this time, when death is very much on my mind, there is an odd comfort in these pages.

The volume opens with “Bear Stories,” a series of very short pieces; raw, visceral prose poems that draw on the intimate complexity of our connection to the natural world. Bound with water, blood, fur, and feather the beauty is shocking, brutal, sublime. Drawn from an earlier longer form chapbook, these “stories” invite us to consider the world at gut level.

In the dark, a body is a pond. The night birds make hollow sounds, and then there is a sound of the mouth, pulled back, curled out. And so on. Fur catches the moon as it comes out barbed and dark. A vertical cut whines under the ribs, and the long grass keeps it from you.

The micro essays and meditations that comprise the central portion of Beastlife are remarkably rich, drawing on a range of literary and critical resources. “A Catalogue and Brief Comments on the Archive Compiled and Written by the Ministry of Sorrow to Birds,” for instance, takes inspiration from Ovid, Heidegger, Barthes, Sebald, Tennyson and more. Despite its seemingly whimsical name, this is a more explicit meditation on death and dying framed against images, photographic and descriptive, of dead birds. The ministry of the title is an imagined institution dedicated to a form of archival lamentation, an understanding of death and mourning through the collection of photographic specimens. They seek and gather images into a growing chronicle of sorrow:

We were stopped, and looked down, in the walk by the bird, flies, cigarette, glint of coin. We saw the futility in keeping—the ornaments in hydriotaphia and their obsidian speaking something of its keeper. But the detritus we die alongside or do not die alongside, the litter jettisoned from our death and dying bodies or we die too quickly to regard, utter the currency of living things.

And there is this discomfort: the spectacle. Its hard edges. We have bodies too, we say, and we want them wrapped in webby husk, a film, a membrane huddled into self. But our bodies are still over-looked by our own flânerie, in which the world, and its subtle schism of that which is alive and that which is dead, becomes our final coup for all we have lost in the leaving. All the unmeasured ether, it flames with our light.

In death we are confronted with the fragility of the body—the body of the one who has died and, in reflection, our own. In her next essay, “We Continue to Unskin: On Taxidermy,” following Truth’s advice to Petrarch to constantly meditate upon his own mortality, Chapman contemplates mortality and the miracle of immortality which, paradoxically involves an engagement with death. Structured along lines from a poem by Paul Celan, this journey takes us through the a more familiar archive of natural history. From the delicate art of the taxidermist, preserving the form and imitation of natural life in the animal’s natural habitat, to the narrator’s own relentless search to find her place in the urban spaces she inhabits, the promise of immortality lies, of course, in language.

And yet every sentence has its beginnings and each animal, posed as it is in flight or in fright has its past-tense. Beauty, eternal gesture. I want to write sentences that stretch on toward desperation, as in the fugal voices that become discordant but still lovely, then recollected in harmony. At the apotheosis of the desperation, the line would break into clause or new sentence and the break would be the point of discord rather than calm, and still the dissolution would be reprieve, as when the healthy mind refuses any more annihilation and in its descent decides to rest. But there must be sentences that travel toward the desperate one. There must be travel.

The last entry, “Our Final Days,” echoes in form the contained short prose pieces of “Bear Stories,” but here the brutality is decidedly human—dispatches of cruelty, violence, and injury are played against the hope that some semblance of beauty in nature may preserve us. It’s a faint hope, a lament of an entirely different order. It’s too easy to get wrapped up in the disheartening news that floods our lives through our TVs and news feeds. Sometimes I find myself relieved that my parents will not see any more of the potential darkness that seems to ever loom on the horizon. But then I remember that I have two children. Life goes on. I reorient myself to the future again.

There is a woeful inadequacy that washes over me when I read more conventional memoirs of loss and explorations of grief. I keep peeking into odd corners, turning over rocks to see what crawls out. Reading books like Beastlife.

I keep the other poetic evocations of grief, the books I am amassing, close at hand. I read them to stir up and open the gates that are still secured against the flood of choked tears, the barricades of numbed sadness, that do not seem to be able to allow more than a slow leak in occasional shuddered gasps. At the moment mourning feels more like emptiness. I feel a need to find a starting point with death, with these particular deaths, with watching each one on their deathbeds, before I can find and begin to work through the grief.

Beastlife by J’Lyn Chapman is published by Calamari Archive.