Each year when I review the list of books that I have read, I face the same challenge deciding what to include and what to leave out of a final accounting. As usual there are the books that I know, even as I am reading them, will be among my favourites for the year. Just as I know the ones I don’t like, the ones I won’t even mention or take the time to review. Basically, everything else that I have reviewed, was a good book.

This year, my count far exceeds a respectable “top ten” or “baker’s dozen” and there are some striking factors at play. One is that the ongoing violence in Gaza has heightened my focus on Palestinian and Arabic language literature—long an area of interest and concern. Five of the Palestinian themed books I read made my year end list. As well, I have paired several titles, typically by the same author or otherwise connected, because the reading of one inspired and was enhanced by the reading of the other (not to mention that such pairings allow me to expand my list). Finally, as reflected by my top books, I read and loved more longer works of fiction this year than usual (for me). No 1000 page tomes yet, but perhaps I’m overcoming some of my long book anxiety.

And so on to the books.

Poetry:

I read far more poetry than I review, but this year I wanted to call attention to four titles.

Strangers in Light Coatsevokes by Palestinian poet Ghassan Zaqtan (Arabic, translated by Robin Moger/Seagull Books) is, perhaps, a darker than his earlier collections. Comprised as it is, of poems from recent releases, it actively portrays a world shaped by the reality of decades of occupation and war.

Strangers in Light Coatsevokes by Palestinian poet Ghassan Zaqtan (Arabic, translated by Robin Moger/Seagull Books) is, perhaps, a darker than his earlier collections. Comprised as it is, of poems from recent releases, it actively portrays a world shaped by the reality of decades of occupation and war.

My Rivers by Faruk Šehić (Bosnian, translated by S.D. Curtis/Istros Books) is a collection particularly powerful for its depiction of a legacy of wars in Bosnia/Herzegovina including the genocide in Srebrenica. His speakers carry the burden of history.

Walking the Earth by Tunisian-French poet Amina Saïd (French, translated by Peter Thompson/Contra Mundum) is such a haunting work of primal beauty that I can’t understand why more of her poetry has not been published in English. Perhaps that will change.

Walking the Earth by Tunisian-French poet Amina Saïd (French, translated by Peter Thompson/Contra Mundum) is such a haunting work of primal beauty that I can’t understand why more of her poetry has not been published in English. Perhaps that will change.

Nostalgia Doesn’t Flow Away Like Rainwater by Irma Pineda is one of a number of small Latin American poetry collection from poets and communities that have not been published in English before. This book, a trilingual collection in Didxazá (Isthmus Zapotec) and Spanish with English translations by Wendy Call (Deep Vellum & Phoneme Media) was particularly special.

Nonfiction:

This year, my favourites include a mix of memoir and essay and a couple of works that defy simple classification.

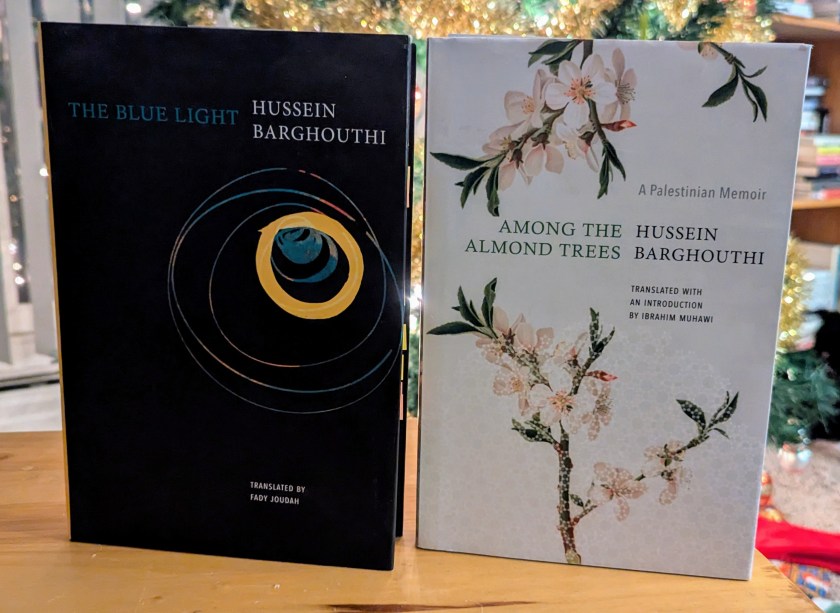

The Blue Light / Among the Almond Trees by Palestinian writer Hussein Barghouthi (Arabic, translated by Fady Joudah and Ibrahim Muhawi respectively/Seagull). Blue Light chronicles Barghouthi’s years in Seattle as a grad student and the eccentric circles he travelled in, whereas Among the Almond Trees is a much more sombre work written when he knew he was dying of cancer. The two books complement each other beautifully.

The Blue Light / Among the Almond Trees by Palestinian writer Hussein Barghouthi (Arabic, translated by Fady Joudah and Ibrahim Muhawi respectively/Seagull). Blue Light chronicles Barghouthi’s years in Seattle as a grad student and the eccentric circles he travelled in, whereas Among the Almond Trees is a much more sombre work written when he knew he was dying of cancer. The two books complement each other beautifully.

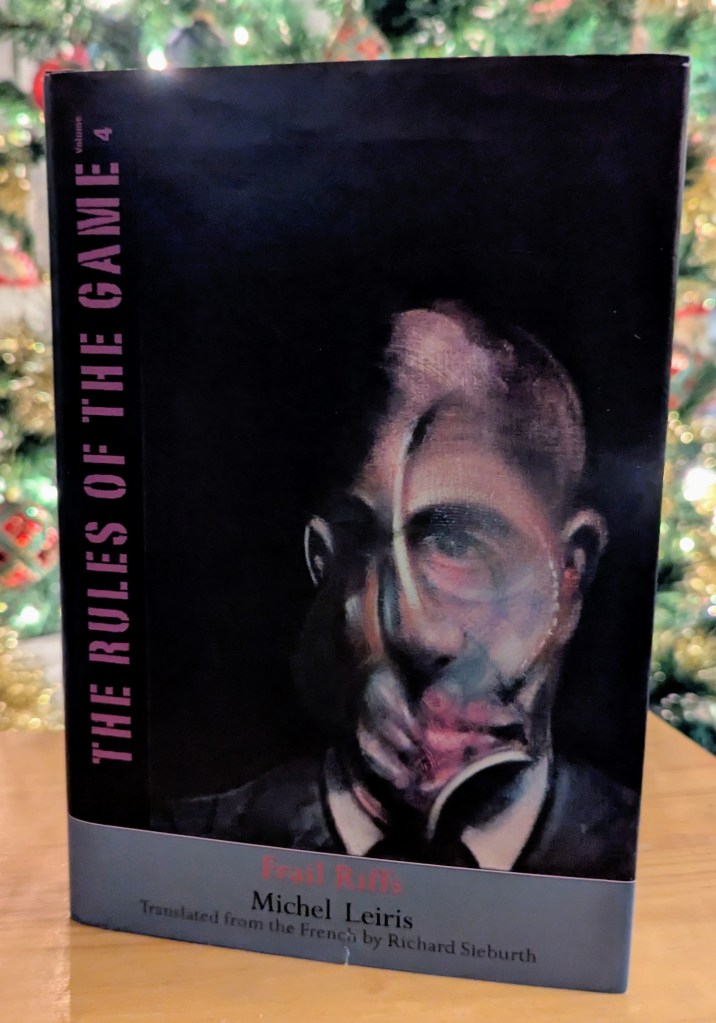

French intellectual, critic, ethnographer and autobiographical essayist Michel Leiris is a writer who means so much to me that the occasion of the release of Frail Riffs (Yale University), the fourth and final volume of his Rules of the Game in Richard Sieburth‘s translation, was not only an excuse to pitch a review but an invitation to revisit the earlier volumes. Definitely a highlight.

French intellectual, critic, ethnographer and autobiographical essayist Michel Leiris is a writer who means so much to me that the occasion of the release of Frail Riffs (Yale University), the fourth and final volume of his Rules of the Game in Richard Sieburth‘s translation, was not only an excuse to pitch a review but an invitation to revisit the earlier volumes. Definitely a highlight.

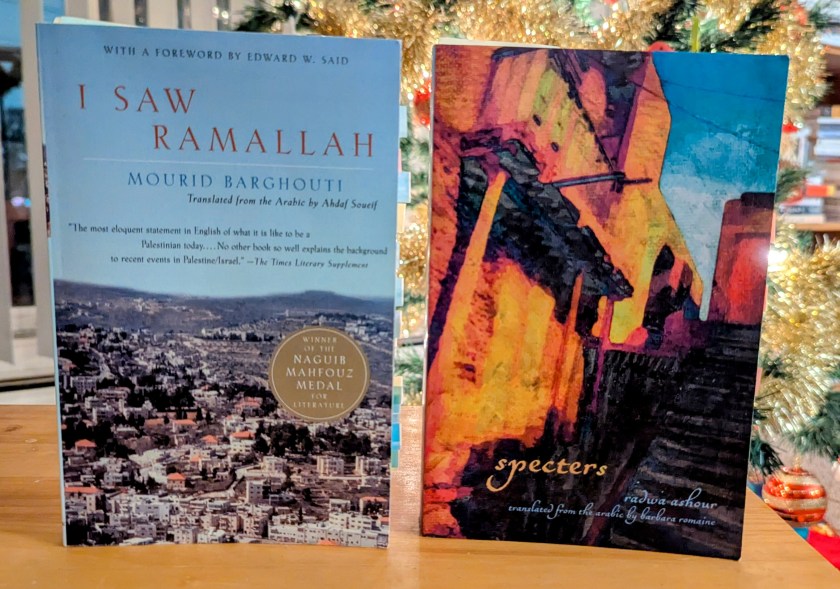

I Saw Ramallah by Mourid Barghouti (Palestinian/Arabic, translated by Ahdaf Soueif/Anchor Books) is a moving memoir detailing the author’s return to his homeland after thirty years of exile. Reading it reminded me that I had a copy of Scepters by his wife, Egyptian novelist Radwa Ashour (Arabic, translated by Barbara Romaine/Interlink Books). This ambitious work blends fiction, history, memoir, and metafiction and I absolutely loved it, but my decision to include it here, like this, rests on the memoir element which complements her husband’s in its account of the many years he was exiled from Egypt—a double exile for him—especially the years in which she travelled back and forth with their young son to visit him while he was living in Hungary.

I Saw Ramallah by Mourid Barghouti (Palestinian/Arabic, translated by Ahdaf Soueif/Anchor Books) is a moving memoir detailing the author’s return to his homeland after thirty years of exile. Reading it reminded me that I had a copy of Scepters by his wife, Egyptian novelist Radwa Ashour (Arabic, translated by Barbara Romaine/Interlink Books). This ambitious work blends fiction, history, memoir, and metafiction and I absolutely loved it, but my decision to include it here, like this, rests on the memoir element which complements her husband’s in its account of the many years he was exiled from Egypt—a double exile for him—especially the years in which she travelled back and forth with their young son to visit him while he was living in Hungary.

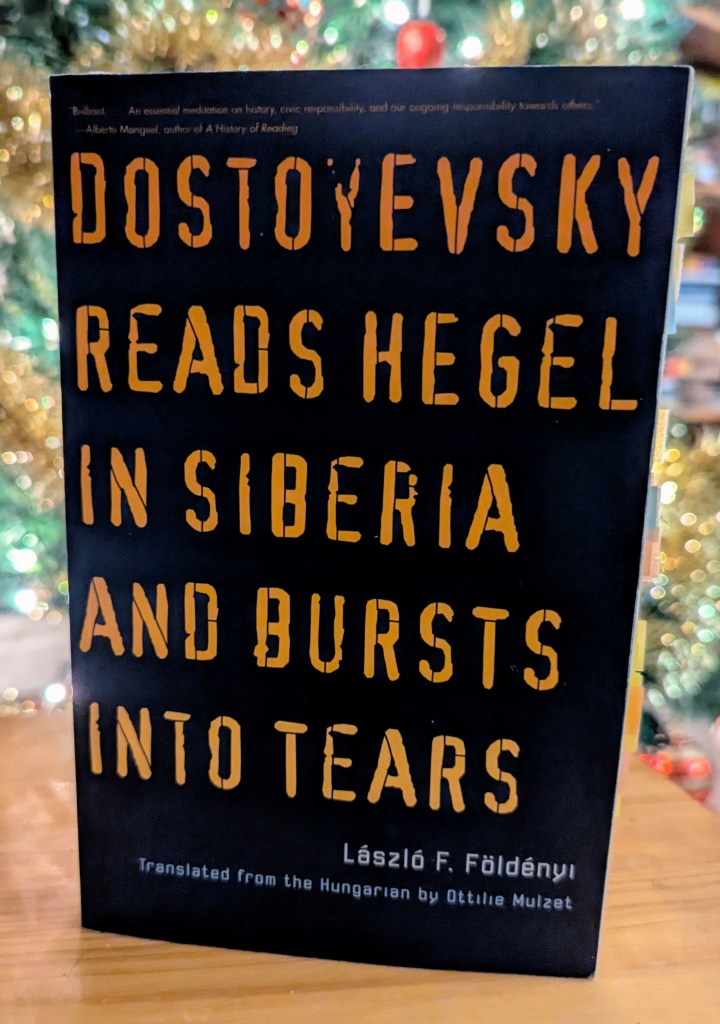

Candidate for the book with the best title, perhaps ever, Dostoyevsky Reads Hegel in Siberia and Bursts into Tears by Hungarian scholar László Földényi (translated by Ottilie Mulzet/Yale University) was an endlessly fascinating collection of essays exploring the relationship between darkness and light (and similar dichotomies) through the ideas of a variety of writers, thinkers and artists.

Candidate for the book with the best title, perhaps ever, Dostoyevsky Reads Hegel in Siberia and Bursts into Tears by Hungarian scholar László Földényi (translated by Ottilie Mulzet/Yale University) was an endlessly fascinating collection of essays exploring the relationship between darkness and light (and similar dichotomies) through the ideas of a variety of writers, thinkers and artists.

Fiction:

As usual, fiction comprised the largest component of my reading and, as I’ve said, I read more relatively longer works than in the past. Normally I have a special fondness for the very spare novella and, of course, my list would not be complete without a few shorter works, including one more pair.

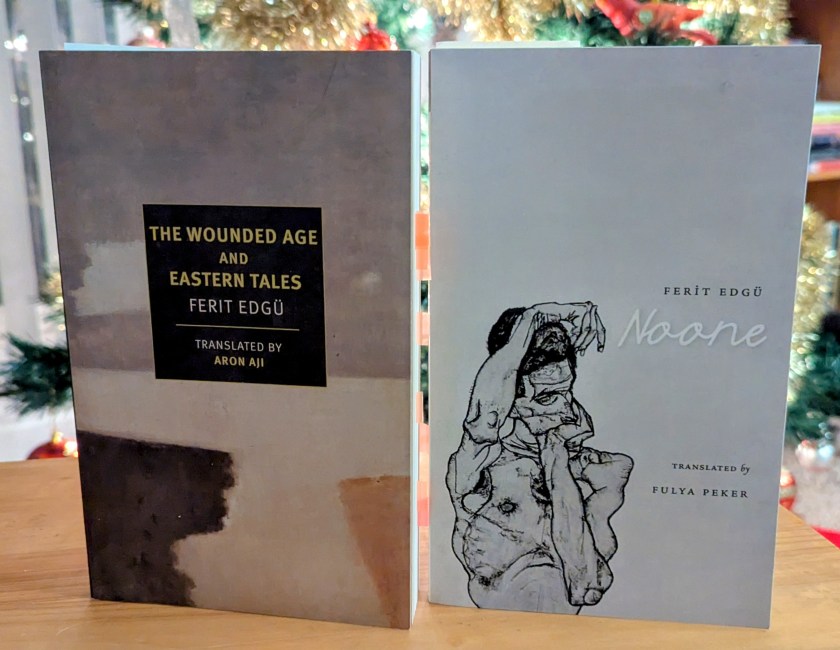

The Wounded Age and Eastern Tales / Noone by Turkish writer Ferit Edgü—translated by Aron Aji (NYRB Classics) and Fulya Peker Cotra Mundum) respectively—who is sadly one of the writers we lost this year. His work, which draws on the time he spent teaching in the impoverished southeastern region of Turkey in lieu of military service, is filled with great compassion for the people of this troubled area. But his prose is stripped clean, bare, and remarkably powerful.

The Wounded Age and Eastern Tales / Noone by Turkish writer Ferit Edgü—translated by Aron Aji (NYRB Classics) and Fulya Peker Cotra Mundum) respectively—who is sadly one of the writers we lost this year. His work, which draws on the time he spent teaching in the impoverished southeastern region of Turkey in lieu of military service, is filled with great compassion for the people of this troubled area. But his prose is stripped clean, bare, and remarkably powerful.

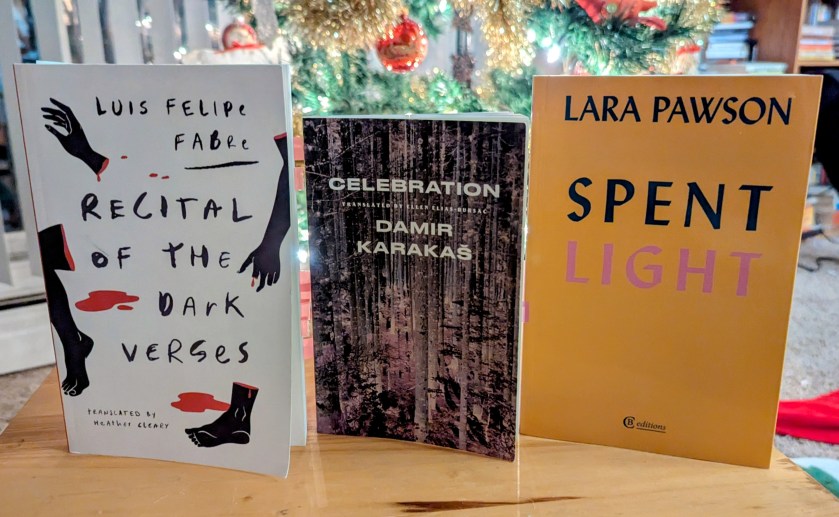

Recital of the Dark Verses by Luis Felipe Fabre (Mexico/Spanish, translated by Heather Cleary/Deep Vellum) is an award wining translation that seems to have garnered less attention than it deserves. This comic Golden Age road trip follows the misadventures of the body of John of the Cross on its clandestine voyage to Seville. Brilliant.

Recital of the Dark Verses by Luis Felipe Fabre (Mexico/Spanish, translated by Heather Cleary/Deep Vellum) is an award wining translation that seems to have garnered less attention than it deserves. This comic Golden Age road trip follows the misadventures of the body of John of the Cross on its clandestine voyage to Seville. Brilliant.

Celebration by Damir Karakaš (Croatian, translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać/ Two Lines Press) is an exceptionally spare, unsentimental novella about the historical forces that pulled the residents of Lika in central Croatia into World War II.

Spent Light by Lara Pawson (CB Editions) is a book I’d been anticipating since reading her This Is the Place to Be. Strange, at times disturbing, often hilarious and always thoughtful, this is one of those books that (thankfully) defies description.

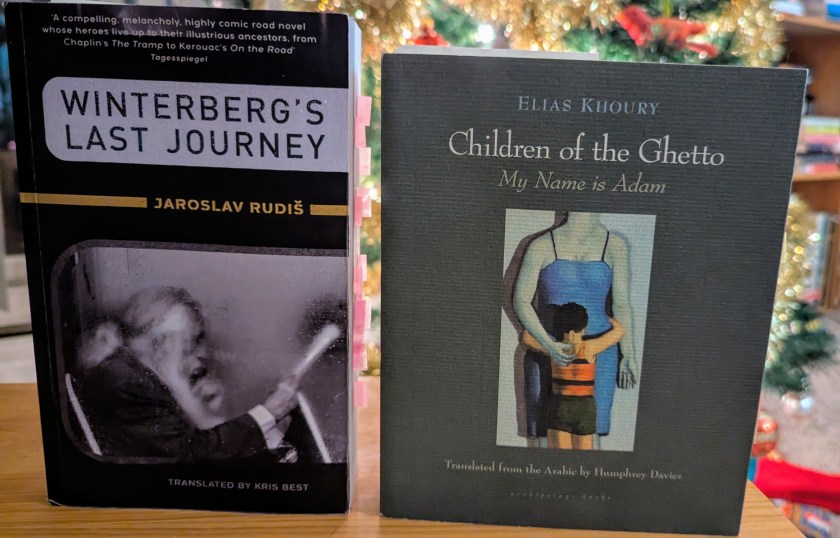

If Celebration is historical fiction at its most spare, Winterberg’s Last Journey by Czech writer Jaroslav Rudiš (German, translated by Kris Best/Jantar Publishing) is the exact opposite. Ambitious, eccentric, and filled with detail, it follows a 99 year-old man and his male nurse as they travel the railways with the aid of 1913 railway guide. What could possibly go wrong?

If Celebration is historical fiction at its most spare, Winterberg’s Last Journey by Czech writer Jaroslav Rudiš (German, translated by Kris Best/Jantar Publishing) is the exact opposite. Ambitious, eccentric, and filled with detail, it follows a 99 year-old man and his male nurse as they travel the railways with the aid of 1913 railway guide. What could possibly go wrong?

Children of the Ghetto I: My Name is Adam by Lebanese author Elias Khoury who also died this year (translated by Humphrey Davies/Archipelago Books) is the final Palestinian themed work on my list. This is a challenging and rewarding novel about a man born in the ghetto of Lydda during the Nakba that examines complex questions of identity.

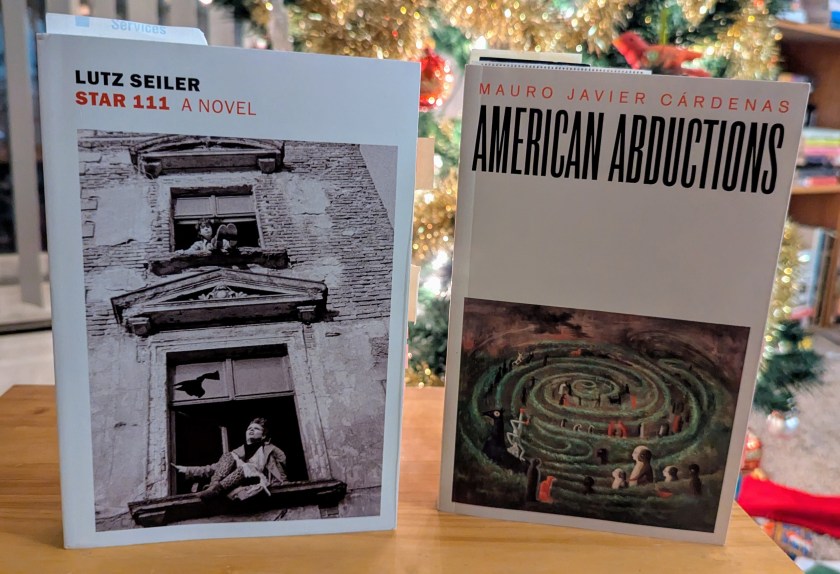

Star 111 by Lutz Seiler (German, translated by Tess Lewis/NYRB Imprints)is the autobiographically inspired story of a young East German would-be poet’s experiences among an eccentric group of idealists in Berlin in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Wall. I was familiar with Seiler’s poetry before reading this, but I liked this novel so much that it lead me to follow up with his essays and the work of other poets important to him—the best kind of expanding reading experience.

Star 111 by Lutz Seiler (German, translated by Tess Lewis/NYRB Imprints)is the autobiographically inspired story of a young East German would-be poet’s experiences among an eccentric group of idealists in Berlin in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Wall. I was familiar with Seiler’s poetry before reading this, but I liked this novel so much that it lead me to follow up with his essays and the work of other poets important to him—the best kind of expanding reading experience.

Mauro Javier Cárdenas’ third novel American Abductions (Dalkey Archive) imagines the latest iteration of his hero Antonio in a future in which Latin American migrants are systematically sought out, separated from the children and deported. With a stream of single sentence chapters, he creates a tale that is both fun and uncomfortably too close for comfort. Quite an achievement!

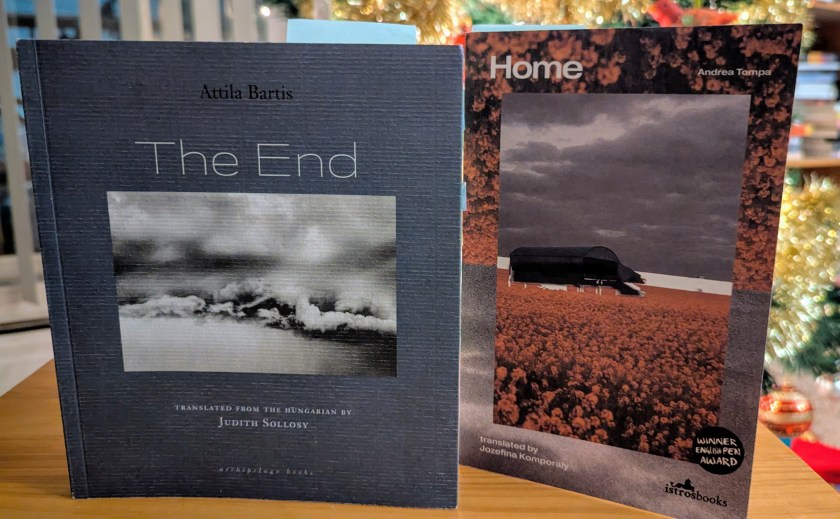

Last but not least, my two favourite books this year are Hungarian:

In The End by Attila Bartis (translated by Judith Sollosy/Archipelago Books), a fifty-two year old photographer looks back on his life—his successes and his failures. He reflects on his relationship with his mother, his move to Budapest with his father in the early 1960s following her death, life under Communism and the secrets held by those around him, and the role the camera played in his life. Presented in short chapters, like photographs in prose each with its “punctum,” the 600+ pages of this book just fly by.

In The End by Attila Bartis (translated by Judith Sollosy/Archipelago Books), a fifty-two year old photographer looks back on his life—his successes and his failures. He reflects on his relationship with his mother, his move to Budapest with his father in the early 1960s following her death, life under Communism and the secrets held by those around him, and the role the camera played in his life. Presented in short chapters, like photographs in prose each with its “punctum,” the 600+ pages of this book just fly by.

Like Attila Bartis, Andrea Tompa also comes from the ethnically Hungarian community of Romania’s Transylvania region and now lives in Budapest. Her novel Home (translated by Jozefina Komporaly/Istros Books) follows a woman travelling to a school reunion, but it is much more. It is a novel about language, about what it means to belong, to have a home and a mother tongue. It’s probably not surprising that my two favourite novels involve protagonists in mid-life, looking at where they are and how they got there. As to why they’re both Hungarian—I suppose I’ll have to read more Hungarian literature in the new year to answer that.

So that is my 2024 wrap up. I’d like to think 2025 will be better than I fear it will, but at least I know there are countless good books to look forward to.

Happy New Year!