The first thing I think to write is this: what’s happening to me is incredible. But immediately, I stop—I’m suspicious of everything. I think about it, reread the sentence, and the pen slips through my fingers and falls to the floor. It bounces and flips in the air, does some involuntary acrobatics. Describing what’s concrete is easier.

(from “Astronaut”)

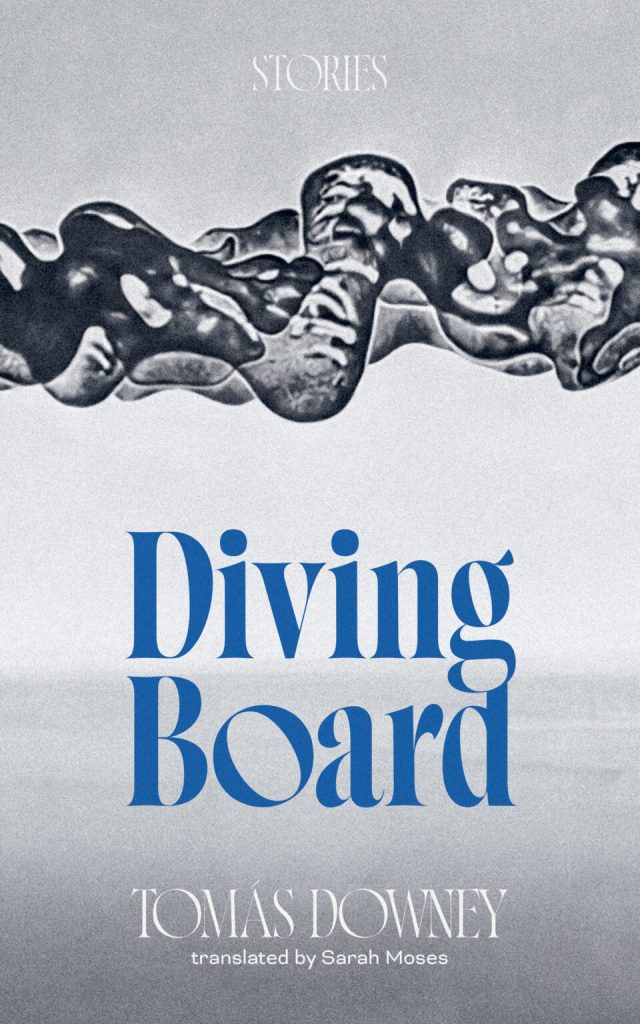

If there’s a common feature uniting the nineteen stories gathered together in Diving Board, Argentinian writer Tomás Downey’s first collection in English translation, it’s the uncomfortably close focus he places on the experiences of his narrators or protagonists. His lens is so tight that the edges of the world around them becomes increasingly distorted, leaving them emotionally isolated and alone. Consider “The Astronaut” quoted above, for instance. The narrator is a man who has inexplicably found himself freed from the restraints of gravity, a condition that has literally turned his world upside down. Only at ease resting on the ceiling, every time he returns, even briefly, to the floor he is struck by waves of dizziness and nausea. There is no magic in this altered reality; everyone else, his wife included, remains grounded, unreachable. He decides there is only one means of escape—an open window.

Born in Buenos Aires in 1984, Downey is one of Argentina’s foremost short story writers, a master of a strangely unsettling terrain that his fellow Argentinian writer Mariana Enriquez refers to as bizarro fiction, not a genre but: “a disturbing variant that hides a vague threat, that leaves the reader feeling something between awe and unease.” As such, his stories vary from harsh realism to fantasy to horror to speculative fiction, but regardless of form, he tends to minimize set-up and avoid resolution altogether, intensifying the tension. In most instances, his settings lack excessive detail which allows circumstances, personalities, and interrelationships to take centre stage. As a result, even stories that take place in rural settings have a certain pervasive claustrophobia.

Born in Buenos Aires in 1984, Downey is one of Argentina’s foremost short story writers, a master of a strangely unsettling terrain that his fellow Argentinian writer Mariana Enriquez refers to as bizarro fiction, not a genre but: “a disturbing variant that hides a vague threat, that leaves the reader feeling something between awe and unease.” As such, his stories vary from harsh realism to fantasy to horror to speculative fiction, but regardless of form, he tends to minimize set-up and avoid resolution altogether, intensifying the tension. In most instances, his settings lack excessive detail which allows circumstances, personalities, and interrelationships to take centre stage. As a result, even stories that take place in rural settings have a certain pervasive claustrophobia.

Short story collections, especially those that contain so many titles, can run the risk of falling into either unevenness or sameness. With Diving Board however, even if many of the tales involve either couples or families, no two stories are alike. Each treads a distinct terrain. In “The Cloud,” a thick, damp fog settles on a community, driving everyone indoors as the temperature rises and snails and slugs seem to multiply rapidly. A family tries to wait it out as this strange, heavy, wet plague spreads. In “Horce,” a man buys a seed that grows into a horse, a creature he hopes will offer him an excuse to reach out to the woman he loves, but instead the vegetal animal only increases his isolation. And, in the title story, a divorced father takes his daughter to a swimming pool, but when he finally agrees to allow her to jump off the diving board, she disappears into thin air:

Josefina leans over again, gauging the distance. She walks back to get a running start. She runs, jumps. He closes his eyes for a second, they’re irritated by the sun and the bleach. He hears a scream or a laugh. When he opens his eyes, Josefina should be in the air, about to fall, but she’s not. He hasn’t heard a splash either.

While many of Downey’s stories exist on the edge of the uncanny, reminiscent of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone and its iterations, others lean straight into horror with characters who harbour cruel and twisted intentions. The action often stops just as things fall apart or in some vague aftermath. No explanations or reasons are ever offered. But sometimes there seems to be a deeper, more serious message. Such is the case with my favourite piece, “The Men Go to War.” Although it is not tied to any specific conflict, Argentina and other Latin American countries have seen their share of uprisings, coups, and warfare, but in truth this tale could take place anywhere, any time. The setting here lies in the shadow of a brutal war. Jose’s husband Manuel is a soldier. Every day she sits at home, refusing invitations to go out or welcome visitors. She is angry at her husband’s willingness to get involved. Then two officers appear at the door with the grim news that Manuel has been killed. They tell her that the incident occurred in a critical battle. They assure her they are winning:

Jose nods, possibly without listening. She’s used to condolences and accepts them with the hint of a smile, trying to downplay their importance, and always responds with a look that’s melancholic and resigned. She waits for the moment to pass, for nothing further to be said on the subject. Whatever it takes, she needs to believe that Manuel’s death is one fact among many, that it’s not of great importance. Thousands have died, all the women are widows, all the children orphans, winter is almost over, and the roofs of the houses need to be repaired. This week there were bananas at the market. When was the last time there were bananas at the market?

Jose’s measured response only cracks briefly when she is given all that remains of her husband, a knife with a mahogany handle and leather sleeve that had once belonged to his father. But when the men have left, she places it in a drawer. Then, as the days pass and winter begins to give way to spring, the official visits continue repeating the same script. Jose seems to be trapped in some kind of time loop, a repetition she responds to with the same questions, the same acceptance, the same self-control. This is yet another story that dissolves into its mysteries rather than revealing them.

Downey’s haunting, weird tales tend to linger, leaving a discomposing sensation in their wake. But they leave one wanting to move on and find out where his imagination will wander next. His stories have appeared in a number of English language publications, but now with this collection, translated in clear, clean prose by Sarah Moses, a broader introduction to the eerie landscape his characters inhabit is available in one volume.

Diving Board by Tomás Downey is translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses and published by Invisible Publishing.