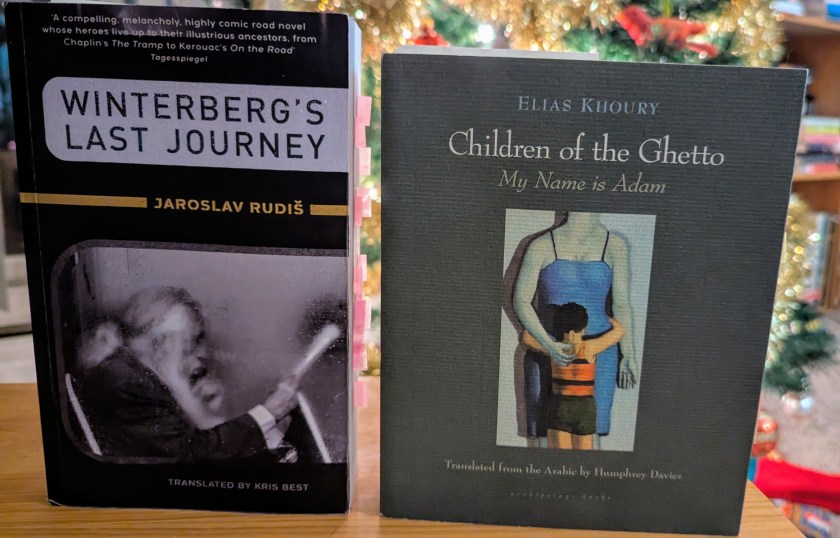

The first volume of Elias Khoury’s Children of the Ghetto trilogy, My Name is Adam, presents itself as a collection of writings by a Palestinian falafel maker living in exile in New York City. Never intended for publication, they include an aborted attempt to write a novel about a seventh-century Yemini poet and the unedited attempt by the author, Adam Dannoun, to understand himself by writing his own story. After a lifetime of trying to leave history, his own and his people’s, behind, two events—the screening of a film based on Khoury’s famous novel Gate of the Sun, and a conversation with a man he has not seen since he was seven years old—motivate this decision to finally commit an account of his life to paper. He will then set the stage for his own death. Elias Khoury supposedly comes into possession of Adam’s notebooks after he has died and, following some consideration, decides to publish them as they are, unedited. The result is an often troubled and circular narrative beginning in New York and making its way back in time in an effort to reconstitute what he knows of his earliest years, during and in the immediate aftermath of the Nakba. Born in Lydda in 1948 he wants to piece together as much as he can about the horrific events of the massacre in the city, the containment of the Arab residents in what the Israeli soldiers labelled a “ghetto,” and the harsh conditions he and his mother endured.

The double-authorship of the first volume—Khoury as the custodian of Adam’s writing—is assumed to be understood, but not mentioned, in Star of the Sea. Rather, the entire tone and approach of the work shifts as Adam steps back from his own story to adopt a distanced perspective: Point of Entry: the Third Person, or the Absent Conscience. That the narrator and author of the novel (and he does call it a novel at this point) is also the protagonist is not a secret, but as he makes clear in the opening passages, it does raise certain challenges:

The double-authorship of the first volume—Khoury as the custodian of Adam’s writing—is assumed to be understood, but not mentioned, in Star of the Sea. Rather, the entire tone and approach of the work shifts as Adam steps back from his own story to adopt a distanced perspective: Point of Entry: the Third Person, or the Absent Conscience. That the narrator and author of the novel (and he does call it a novel at this point) is also the protagonist is not a secret, but as he makes clear in the opening passages, it does raise certain challenges:

The question keeping the writer of these stories awake at night is the following: how can the absentee write? Can they tell their own story using “I,” thereby writing as though remembering? Or should they employ the third person to write in their place?

Pronouns in Arabic are extraordinarily supple, unmatched in any other language. The written letters that take a person’s place are called “consciences”, but since the conscience is also an invisible moral compass, how can a novelist write using the conscience of one who is absent? And finally, what does its corollary—that the conscience must be absent in order for a person to tell their story really mean?

So, although Adam’s account now takes a more straightforward and generally chronological quality, the multi-layered reflective and metafictional elements of the first volume persist, now that the present self (the writer) has separated himself from his past invisible, absent self and reluctant hero of his story.

Although he made passing references to his adolescent and young adult years in the first part of his grand life writing exercise, the primary focus of My Name is Adam was on a period of his life history of which he had either no direct memories or only a child’s recollections. Now, Adam is on much firmer ground, memory-wise, and in a position to try to face his conflicted emotions about the choices he faced as he navigated life in a country to which he could never fully belong. This is, then, a story of one man’s relationship to his own identity and his desire to live without any history or nostalgia. Even if it means living a lie.

This second volume begins in 1963, with fifteen year-old Adam’s decision to leave home. He had moved to Haifa with his mother, Manal, following her marriage to Abdallah al-Ashal, and, after years of watching his relentless abuse drive her further into a lifeless shell, he knew it was time to get away. Manal seemed to know too and, on the night Adam left, she quietly saw him off, handing him his father’s will before he disappeared into the stormy night. He was now on his own.

With a short detour, Adam makes his way to the garage of mechanic named Gabriel, a Polish Jew who had picked him up one night when he was hitchhiking. Struck by the boy’s fair hair and skin, Gabriel saw in Adam the image of his deceased younger brother. He had promised that he could help him out, thinking of possibly teaching him his trade. But Adam was determined to continue his schooling. So the mechanic not only offered him a place to stay in return for odd jobs in the shop, but also helped him get into a Jewish school. His old life now behind him, this period marked the beginning of Adam’s new story. He changed his name from Dannoun to Danon, and with it he assumed a new identity. He looked the part, spoke Hebrew well, and his existing ghetto origin was malleable:

If the heroes of novels could break through the fourth wall (page) and speak without an intermediary, then Adam could very well have told his story not as the invisible man, but a man formed from his imagination. And indeed he had imagined an entire personality that both matched his true nature and was completely different. From the moment he left his mother’s house on the night of the rain, Adam realized that he could represent himself however he wanted by using certain true events to create a compelling background.

This new story follows the reinvented Adam through his first teenage love—unfortunately for him, it is with Gabriel’s daughter Rivka, a situation not destined to end well—into his university years and beyond. Although he enjoys new freedoms with his assumed Israeli identity, he cannot escape his official Arab designation so he often straddles the Jewish and Palestinian communities, spending his days in one and working and living in another. Along the way he meets an assortment of interesting individuals who will influence his life in varying ways, but the central focus of this second volume of Children of the Ghetto lies with the ghetto he where allows others to believe his origins actually lie—in Warsaw.

As a student of Hebrew Literature, Adam develops a close friendship with his German-born professor Jacob Ebenheiner, a relationship based on shared intellectual curiosities and interests. Jacob does not pry into Adam’s life, and the latter offers no details. But a class trip to Warsaw at the end of the first term will ultimately lead to a betrayal of his secret. The visit to Poland has huge impact on the eighteen year-old Palestinian-in-disguise—walking through the streets of the Warsaw Ghetto and listening, through a translator, to the stories of the guide and survivors. But it is an evening spent in the company of Marek Edelmann, one of the leaders of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and life-long anti-Zionist who remained in Poland and became a famed cardiologist, that unsettles him most. Adam is not only left questioning who he is and where he belongs, but it brings to light the extent of the gap that exists between himself and his defiantly proud Israeli teacher.

Throughout this book, Adam relies on a degree of invisibility afforded by his appearance to continue to live a lie into his adult professional life, but in his personal life the balance is more difficult, and not all ghosts can be left in the past, no matter how much he may want them to be. For many years he will keep to himself as much as possible, the personification of the “present absentee.” That is, until he meets Dalia, the young woman who turns his world upside down when he is in his mid-forties, the woman who finally makes him believe in love. But we know, for he has often told us, that it will not last.

Although familiarity with the first volume is assumed, Star of the Sea is building on a much wider story with a fresh angle on questions about what it means to write about one’s own life, about truth, and about what one can really tell. Given his reluctance to talk about his past, Adam does not detail his early experiences, nor does he explain things we as readers know about his true origins, facts that he himself was unaware of until much later in life. Here is focused on telling this aspect of his story in a specific manner. Yet, by the time the novel ends he has glossed over much of what will be the most significant romantic relationship of his life, so one can only assume that Dalia will take centre stage in volume three. But where will Adam be standing as he tells this part of his story? The final part of the trilogy only came out in Arabic in 2023, so it seems that Anglophone readers will have to wait for a translation to find out.

Children of the Ghetto: Star of the Sea by Elias Khoury is translated from the Arabic by Humphrey Davies and published by Archipelago Books.