Somewhere in the city last night there must have been fireworks, officially that is, I’m sure illegal sparklers were also fired. It was Canada Day, after all. July 1. This same holiday back in 1987, marks the day I finally quit smoking for good. I’m quietly hoping that this year July 1 will be remembered as the day my son quit drinking. We’ve stood at this precipice so any times before, I’m almost afraid to believe it might be true. I’ve said it before, I know, but this time really feels different.

The last few months have been especially difficult. In May my son’s computer was hacked. We stood in horror and disbelief, watching as the hacker systematically and openly carved his way through programs while outside no less than five firetrucks descended on the building next door. The excitement at the neighbours’ subsided, but in our home the damage was done. A text to my daughter, whose boyfriend is a computer tech, provided guidance for the initial security steps, and by the weekend the virus was isolated, the hard drive wiped, and rebuilding was underway. But for my son, a tidal wave of anxiety had been unleashed. And it continued to build. His preferred remedy, as it has been for the past fifteen years, was to drink more than ever. He is thirty-five.

Over the years, I’ve learned the hard way that it does no good to confront him or to overreact. Begging, bribing, and passive aggressive accusations are counterproductive. Or worse. Now that his other parent has been diagnosed with high blood pressure, diabetes and, after repeated small strokes, early onset dementia (and this without a history of alcoholism), the medical risks of his addiction have taken on a new intensity. But the thought of facing panic attacks “alone” and the very real nightmare of withdrawal have long stood in the way of any true desire to quit. Each time I’ve suggested he seek support (something that he has tried over the years, of course) I see that the legacy of his abysmal experiences in the child and adolescent mental health system run deep. And I cannot blame him at all, I’m still angry about the way he was mistreated.

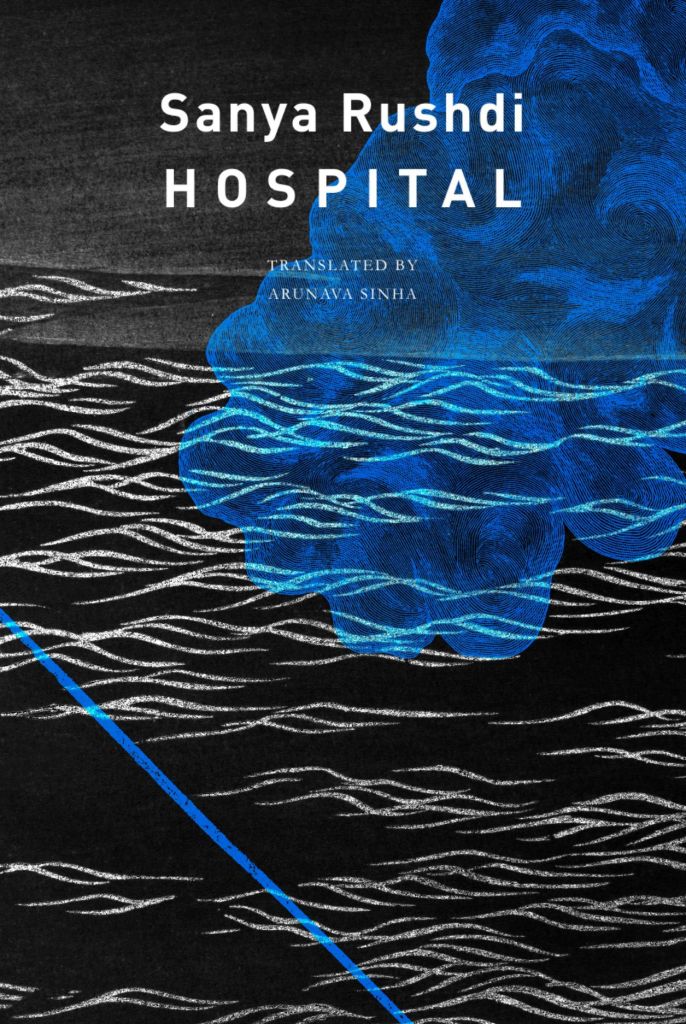

However, something changed in the past few days. Suddenly beer no longer tasted good. No longer provided relief. Made him feel ill. Frightened by the symptoms, he finally agreed to call the public health nurse and after assessing his condition she recommended he go to the hospital emergency. So that’s where we were when fireworks rang out, and where we were until after three o’clock in the morning. At one point my son insisted we leave as no one had been called in to see a doctor since our arrival, but I insisted he inform the triage nurse and when she saw him he was experiencing serious symptoms of detox. She convinced him to take some medication to help him relax and before long his name was called.

However, something changed in the past few days. Suddenly beer no longer tasted good. No longer provided relief. Made him feel ill. Frightened by the symptoms, he finally agreed to call the public health nurse and after assessing his condition she recommended he go to the hospital emergency. So that’s where we were when fireworks rang out, and where we were until after three o’clock in the morning. At one point my son insisted we leave as no one had been called in to see a doctor since our arrival, but I insisted he inform the triage nurse and when she saw him he was experiencing serious symptoms of detox. She convinced him to take some medication to help him relax and before long his name was called.

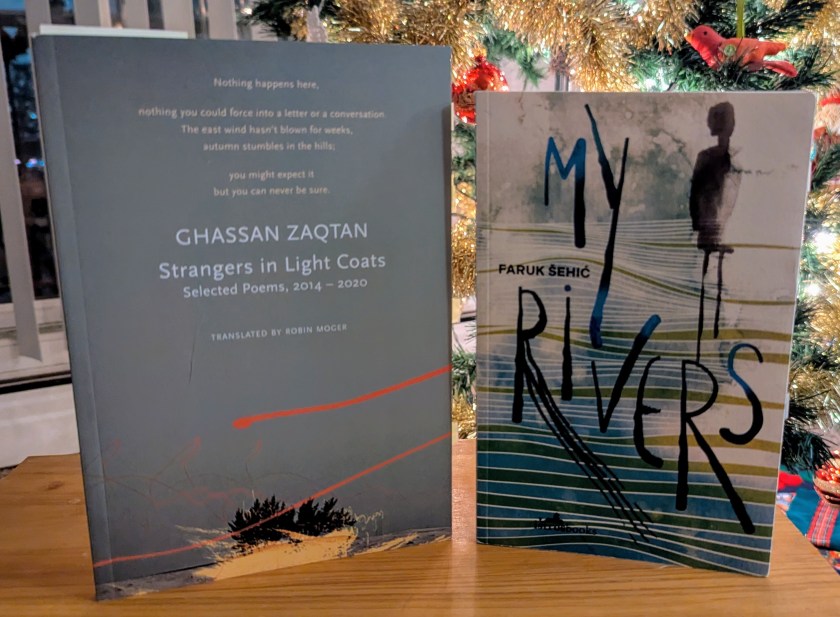

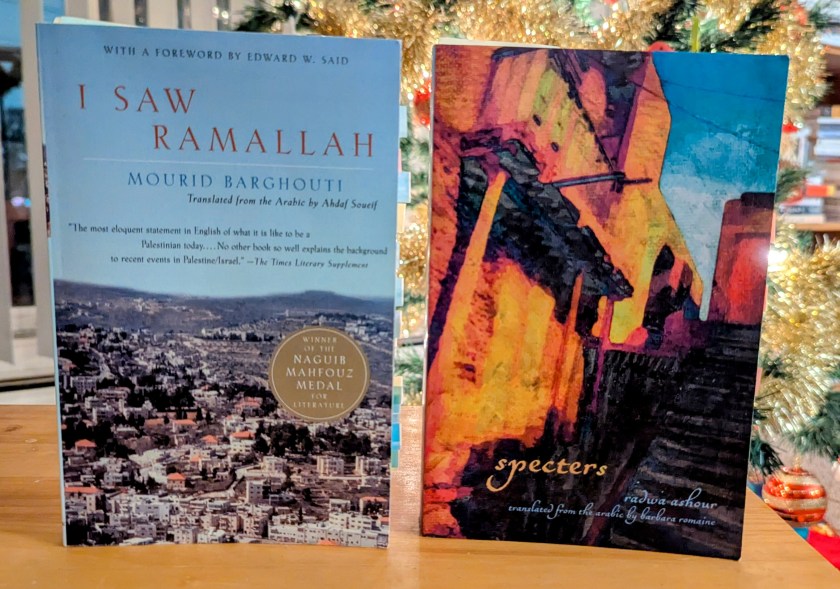

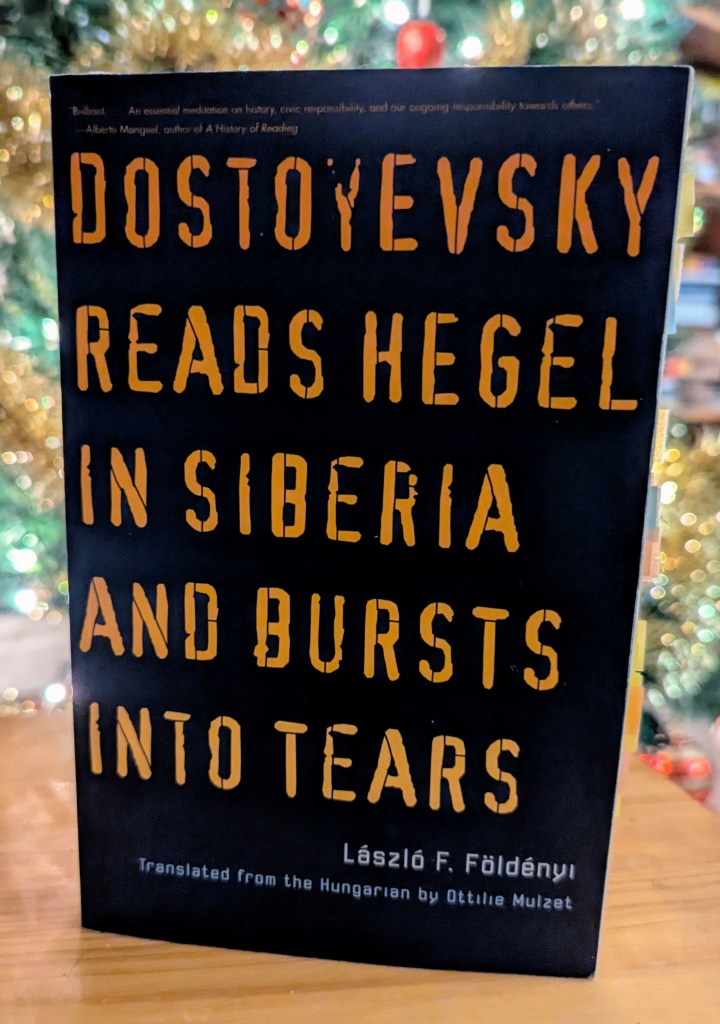

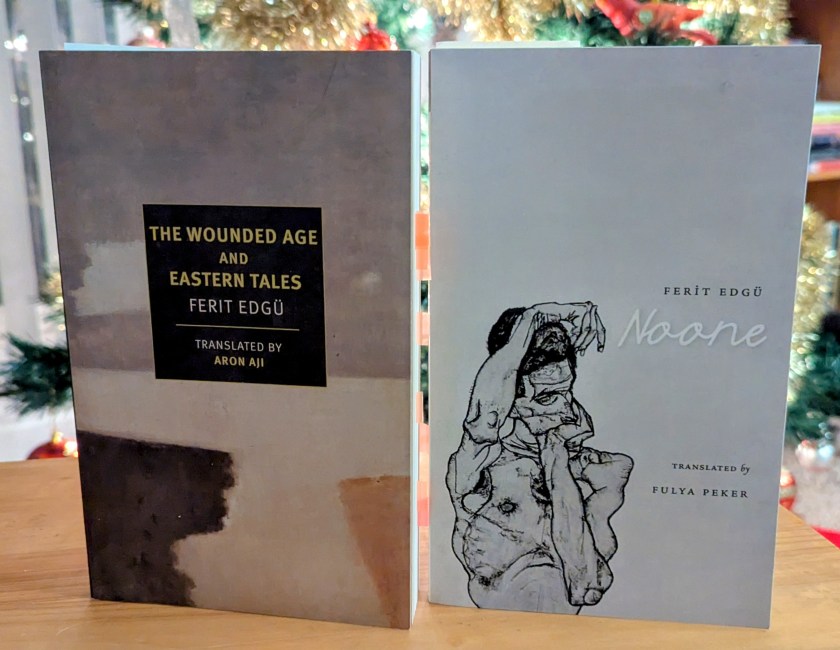

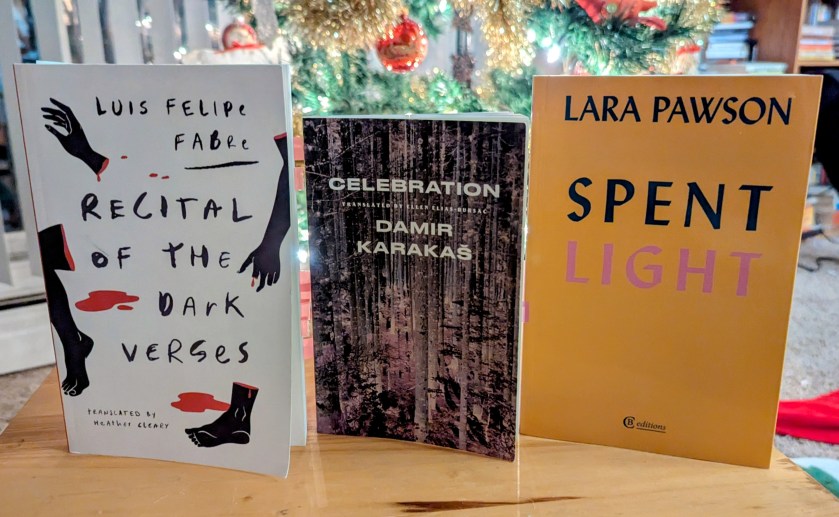

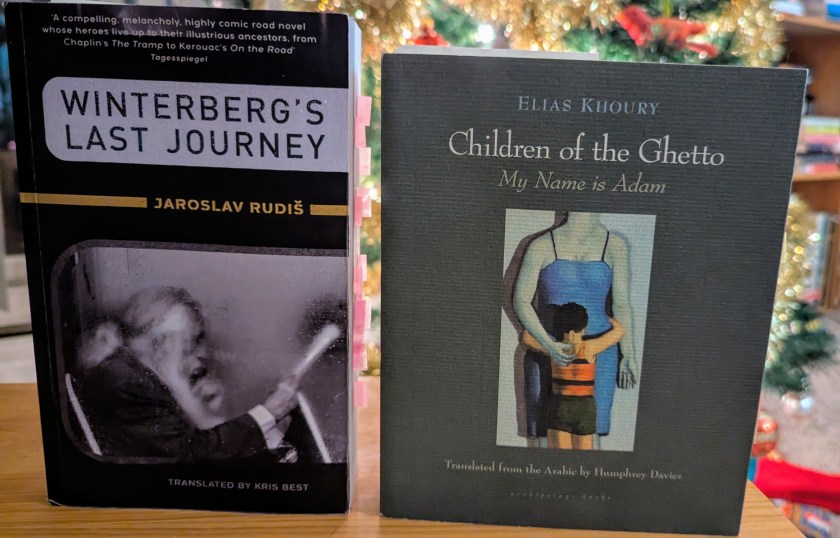

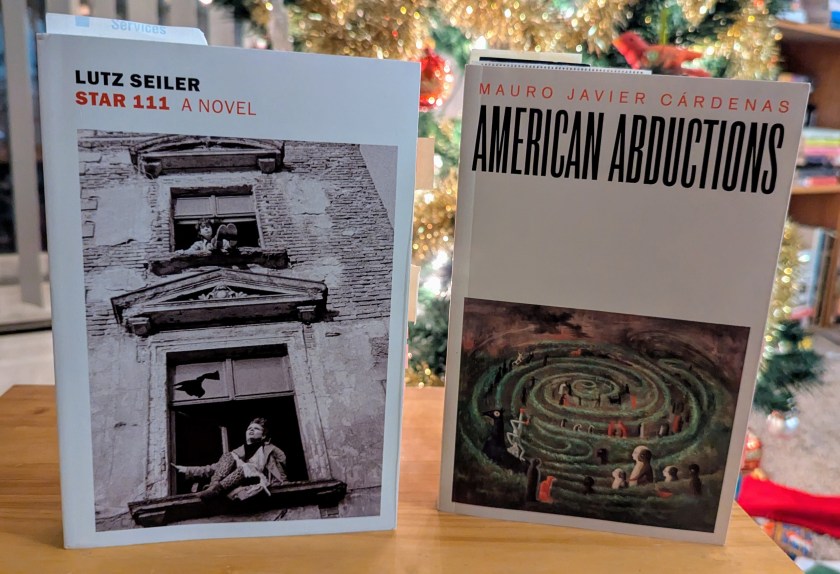

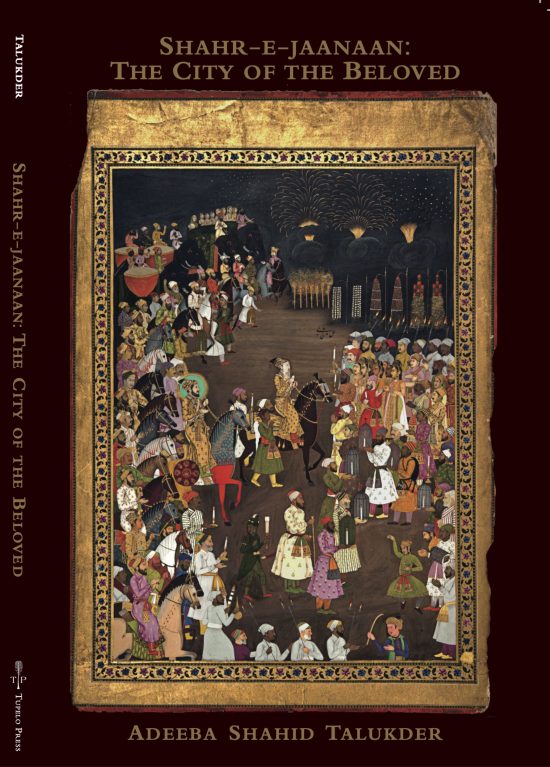

I stayed in the waiting room, hoping to finish the book I was reading. I only had about 20 pages to go when we arrived (in fact, I tucked several books in my pack figuring I would be moving on to something else before the night was out). But then a couple arrived and the woman started listening to an evangelical sermon aloud, on her phone. Stressed and tired, I could not shut it out. I thought, God gave us headphones, surely you could use them. Fortunately, it was not too long before I could go back and join my son.

Now, the road he has ahead will not be easy. He has been drinking so heavily on a daily basis it is no less than a miracle that his blood work came back as good as it did. He has been prescribed medications to reduce cravings and protect against seizures, but he doesn’t seem keen on the side effects (which unfortunately are not unlike the withdrawal symptoms). For someone who has admittedly self-medicated for so long, my son is skeptical about anything that comes from the pharmacy. All I can do is support him with patience and love. This is the first time he has sought medical support, fully and openly admitting to his circumstances, and I am so proud. And cautiously optimistic.

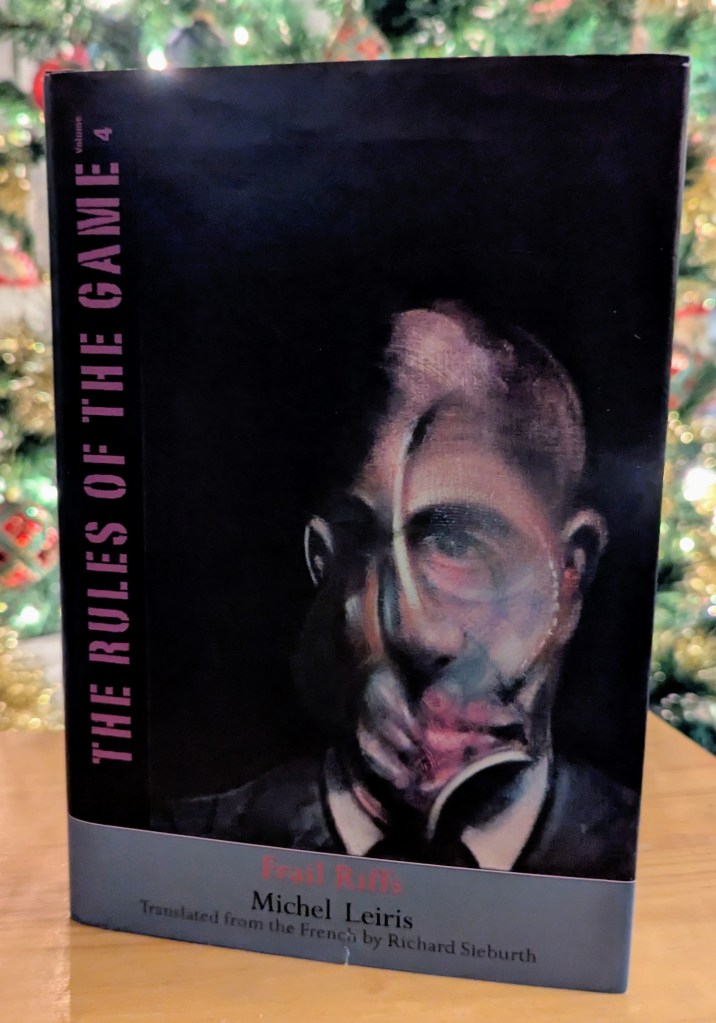

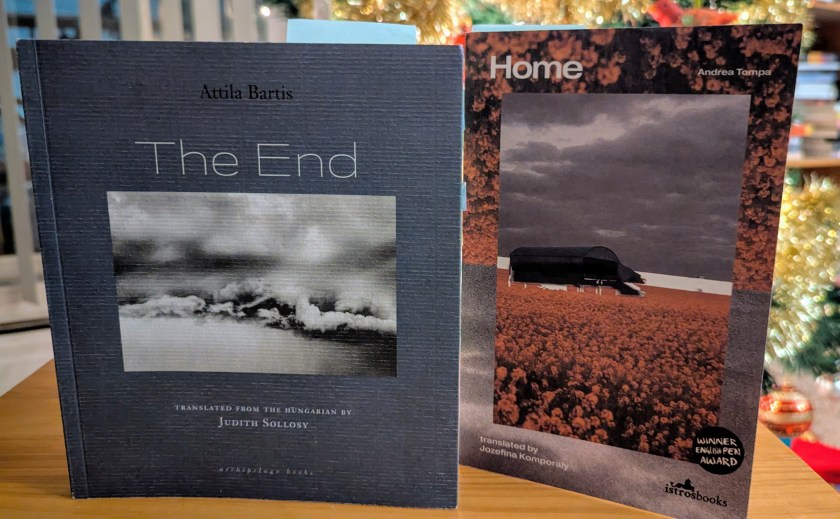

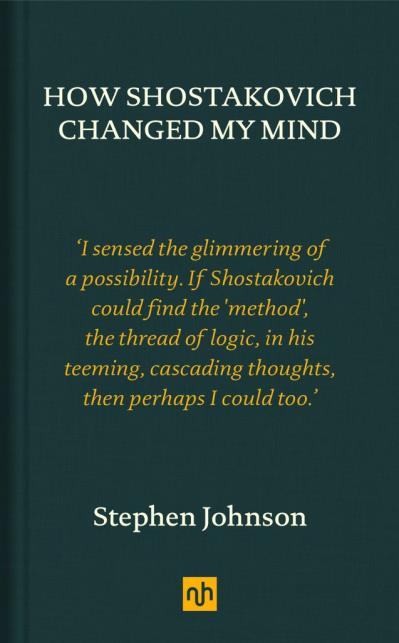

The strain of living with an alcoholic takes a toll. Over the last month and a half I have been distracted, stressed, irritable. I could see that things were escalating, that my son was not coping, but I knew that he had to be ready to take things into his own hands. Meanwhile, I’ve struggled to focus on reading and writing, moving through words at a glacial pace, picking up and putting down book after book after only a few pages. Funny, but only the dream-filled madness of Zuzana Brabcová’s novel of detox, Ceilings has consistently cut through my own anxiety. If I can see my son safely through the next few days of early detox, maybe things will finally be back on track for me—and on to a new future for him.

Note: I debated whether I should write this or not, but decided I needed to put it out there.